Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Women workers have come a long way—but the fight continues

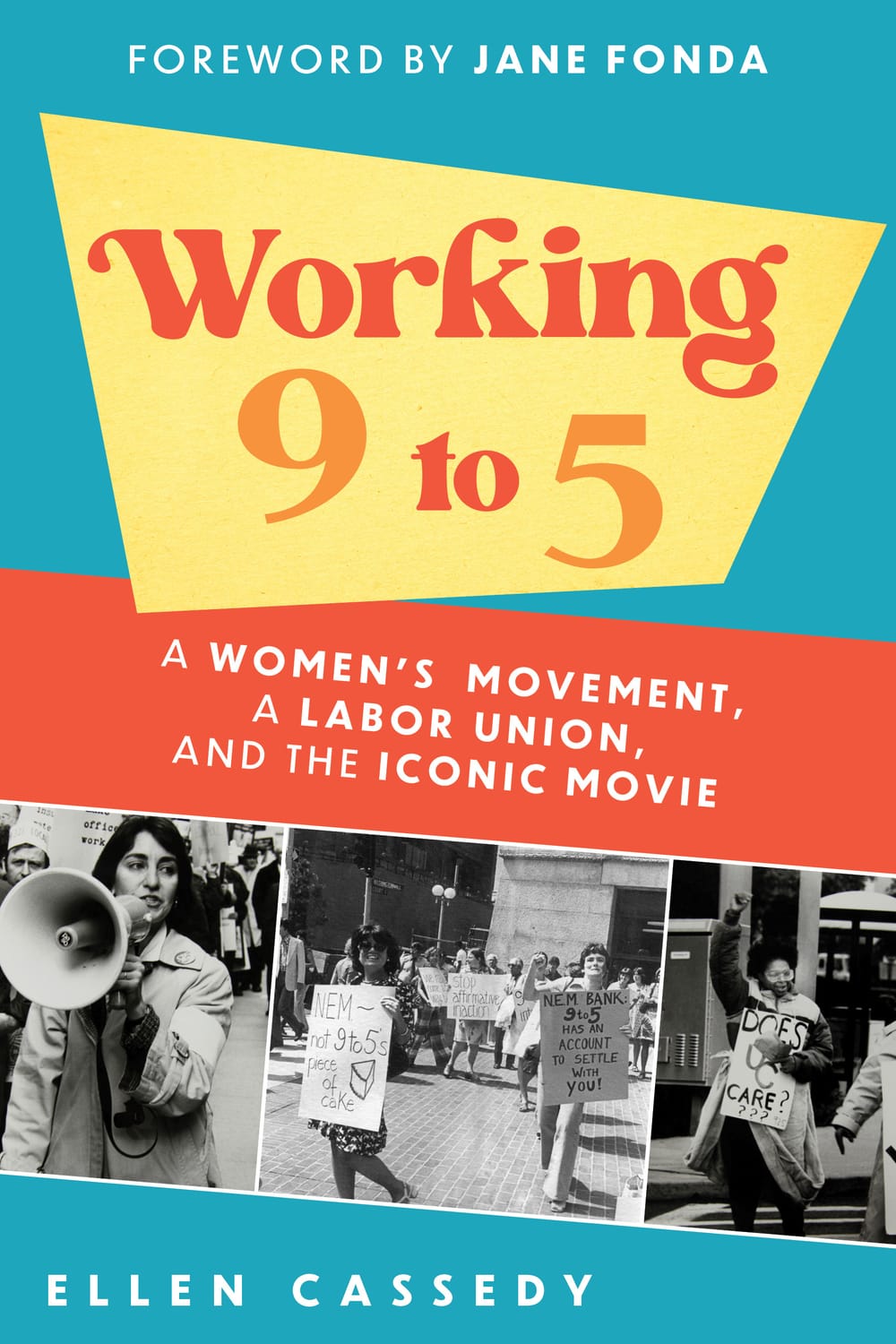

Working 9 to 5: A Women’s Movement, a Labor Union, and the Iconic Movie, by Ellen Cassedy

Before it was a Broadway musical, a blockbuster film, and a finger-snapping song by Dolly Parton, 9 to 5 was a women-led labor movement that began with a tiny group of activists handing out mimeographed newsletters on a blustery winter morning.

It was 1972. The term “sexual harassment” hadn’t yet been coined. White women earned 58 cents for every dollar earned by men; women of color earned 54 cents. One-third of working women spent their days typing, filing, transcribing, and photocopying in glass towers or one-room offices.

Ellen Cassedy was one of 10 women braving the Boston chill on a December day. In Working 9 to 5: A Women’s Movement, a Labor Union, and the Iconic Movie, Cassedy, a former columnist for the Philadelphia Daily News, tells the story of how 9 to 5, the movement, transformed attitudes and workplaces across the county—from behemoth banks to tiny publishing houses, universities to mom-and-pop insurance firms—through relentless, often ingenious, emphatically collective action.

Not-so-distant history

It’s also a coming-of-age story because her work in the movement (from street-corner canvasser to director of the organization’s office in Washington, DC) changed Cassedy, too—from tentative follower to confident, savvy leader.

And at a time when union organizing is aflame again—Amazon! Starbucks!—this book also serves as a roadmap, chronicling the strategies that worked (and the ones that flopped) as a fired-up group of Boston office workers turned individual grievances into significant policy change.

Cassedy tells the story of 9 to 5 in straightforward, unfussy chronology, setting context that’s crucial for today’s young activists, for whom the 1970s may seem like dusty history.

It was a time of crackling possibility: the 9 to 5ers were informed and inspired by the civil rights movement and by struggles for labor justice in the 1930s and 1940s. At the same time, office work had shifted over the course of the 20th century from a highly-paid job for men into a low-paid job for women.

Now was the time

Cassedy was a 22-year-old office worker at Harvard University when her best friend, who worked in the same department, gathered a group of women office workers to talk about their jobs.

Cassedy told about the boss who asked her to remove a calendar from his wall and about the philosophy professor who wanted her to transcribe handwritten notes of all the blowjobs he’d received. (She complied.)

Such incidents were commonplace. The women chronicled them, along with cartoons and accounts of small office rebellions, in their newsletter. Later, they prepared a strategy paper, writing that “now was the time to awaken women and their employers, unions and government, the media and the public at large, to the realities of working women’s lives. And not only to bring those realities into the open, but to change them for the better.”

But how? A six-week summer school in Chicago for women organizers gave Cassedy strategies to bring home to her Boston cohort: win reforms that improve people’s daily lives, make sure they see those changes as rights they’ve achieved through collective effort, alter existing power relations.

A bill of rights for women in the office

The 9 to 5ers held dozens of one-on-one conversations with women office workers. They asked about salaries, benefits, discrimination, and treatment by bosses. They hosted a “forum for women office workers”—the fliers were pink, with a sketch of a typewriter—at a YWCA in 1973. The room filled with 150 office workers, there to learn about women workers’ legal rights and hear about the group’s plan: to document facts about office work in Boston and share them with the Chamber of Commerce.

The next day’s Boston Globe headlined: “HUB Women Office Workers Unite for Higher Pay.” The 9 to 5ers figured they were on their way.

Not so fast. The Chamber of Commerce declined to cooperate, noting that “salaries and conditions of work are the responsibilities of individual firms.”

So they held a public hearing, drafted a “bill of rights” for women office workers and celebrated small victories: a tech company that agreed to cover obstetrical expenses for single, as well as married, women, and a tiny insurance agency where two women agitated for higher pay … and got it.

The law, the score, and bad bosses

Over time, the 9 to 5 group developed a three-pronged strategy. First, they used government pressure to enforce laws prohibiting race and sex discrimination in hiring and employment. They created workarounds for women who feared that speaking up could cost them their jobs: anonymous “scorecards” workers could use to share their companies’ practices.

Finally, and gleefully, they used the tactic of public embarrassment. They ran “bad boss” contests across the country—one nomination was for a man who required his secretaries to cup their hands so he could use them as ashtrays—and staged media-worthy events, including a giant coffee cup parked in the middle of Boston’s City Hall Plaza during National Secretaries Week.

The birth of Local 925

Eventually, the Boston group unionized, becoming Local 925 of the Service Employees International Union and helping office workers in other cities to do the same. They targeted one sector after another—publishing, insurance, banking, higher education—and achieved successes in pay equity, anti-discrimination policies, and grievance procedures.

As the 9 to 5ers went national, they intentionally expanded into cities with racially diverse workforces. They publicized patterns of race-based bias on the job. And when the movie starring Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton hit screens in 1980, they used the film’s success as a spur for rallies, recruitment, and, finally, a national union, District 925, launched in 1981.

That effort smacked into the union-busting, business-favoring policies of Ronald Reagan’s administration; though District 925 prevailed in nine union elections covering 4,000 workers, they won only six contracts covering 800 workers.

Today, in the wake of #MeToo, a growing gig economy, and a renewed thirst for unionization, Cassedy’s book is both cautionary and hopeful. Change is possible with persistent, often tedious, collective action. And the freedoms won by one generation may have to be fought for again.

What, When, Where

Working 9 to 5: A Women’s Movement, a Labor Union, and the Iconic Movie. By Ellen Cassedy. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, September 2022. 272 pages, hardcover; $28.99. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman