Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

America’s pastime sheds new light on our 20th-century history

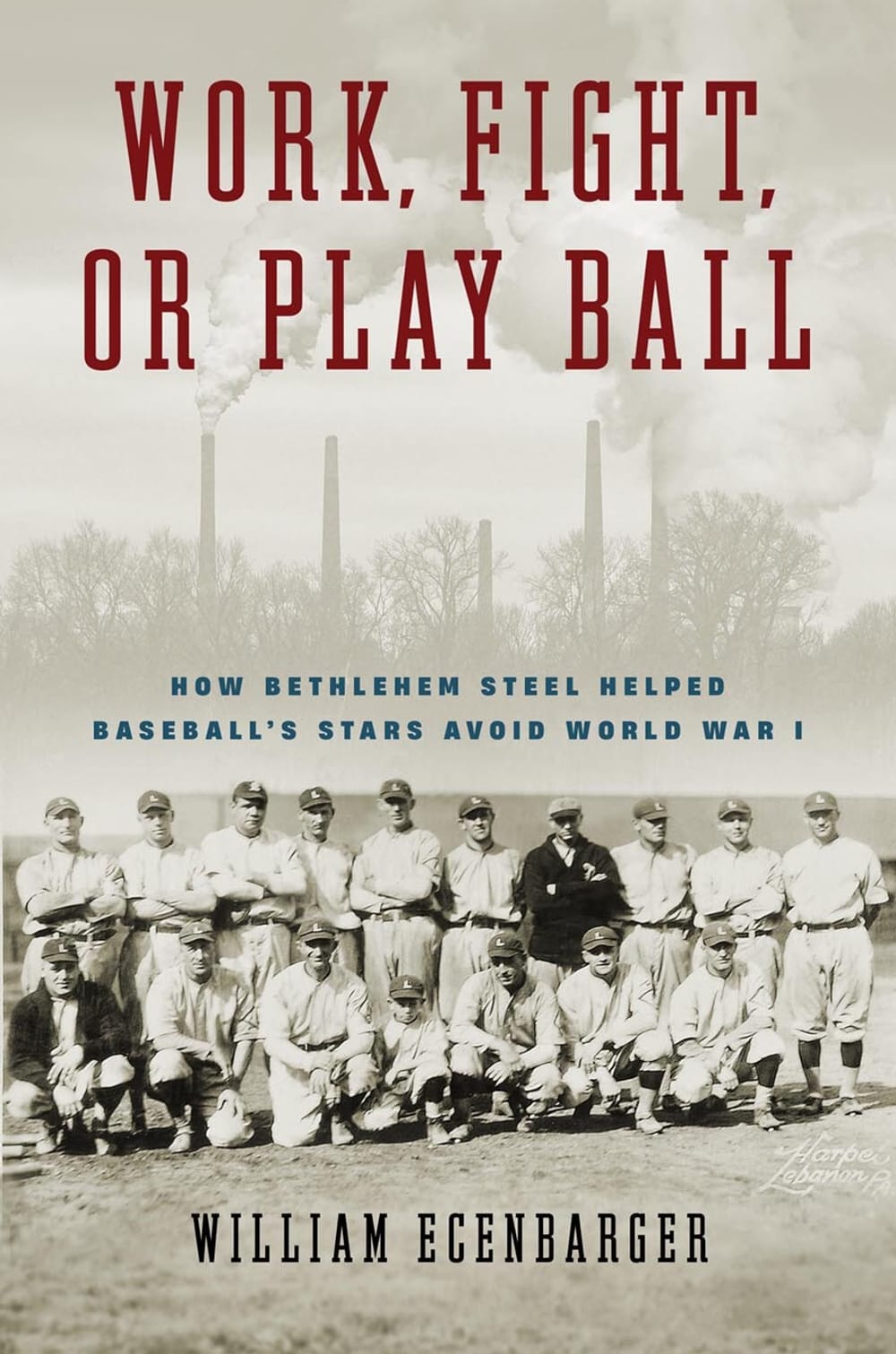

Work, Fight, or Play Ball: How Bethlehem Steel Helped Baseball's Stars Avoid World War I, by William Ecenbarger

At first glance, the subtitle of William Ecenbarger’s new book is a head-scratcher. What’s the connection between Major League Baseball and Bethlehem Steel? Even I, a non-fan, know that baseball bats are not made of steel. Work, Fight, or Play Ball: How Bethlehem Steel Helped Baseball’s Stars Avoid World War I is a baseball book for sure, but also an exploration of a little-known sidebar to America’s war history.

We began calling baseball “America’s Pastime” in the mid-19th century, and its patriotic identity accelerated with the entry of the United States into World War I in 1917. Daily wireless reports to naval ships always included a summary of the day’s games, and war correspondents said the most frequent question they received from troops was about the performance of Babe Ruth.

The draft comes for baseball

As more and more recruits were needed, President Woodrow Wilson instituted a draft. Intent on avoiding the loopholes in the Civil War draft, when it was not uncommon for men to hire a substitute to serve, the Selective Service Act of 1917 allowed only a few exemptions: dependents, religious objections, and “essential occupations.”

At first, Major League Baseball took the stance that the game was essential to keep morale up on the home front. Players would enter the field in military formation, owners would buy Liberty Bonds, and teams would make donations to war charities like the Red Cross or the Soldiers’ Smoke Fund, which provided cigarettes to servicemen.

But with sentiment running high against “slackers” and more troops needed, the government tightened the definition of “essential” to steel-making, munitions, shipbuilding, and farming.

The factory team era

Enter the industrial baseball leagues. In this time period, large factories would often organize baseball teams for their employees and play games against other company teams. Couched as a benevolent gift, the owners hoped the leagues would be a deterrent to union-organizing efforts and that the Sunday games would keep the workers out of taverns, improving Monday attendance and performance.

With its ownership of six steel mills and shipyards, Bethlehem Steel ran two such leagues, the eponymous Bethlehem Steel League and the Delaware River Shipbuilding League, which included other shipyards from Bristol to Baltimore.

What followed was a marriage of convenience of sorts. Major League Baseball stars like Babe Ruth and Shoeless Joe Jackson were hired by the steel mills and shipyards, thus becoming “essential workers,” but often, playing baseball all day. The industries in turn saw a huge boost in attendance at their games.

Unsurprisingly, when the war ended on November 11, 1918, most of those stars quickly returned to their major league teams.

For fervent fans

Ecenbarger has meticulously researched and detailed this now little-known story. He was greatly aided by newspaper accounts; in that pre-broadcast era when even small cities like Lebanon, Pennsylvania, had multiple daily papers, their reports detailed the major plays, stats, and attendance numbers for every game. It offers more than enough stats, name-dropping, play-by-play accounts, and management intrigue to satisfy even the most fervent baseball fan.

He also presents the stories of the players who opted to join the military, including Ty Cobb, who volunteered for the Chemical Warfare Service.

There’s quite a bit of baseball lingo sprinkled in, occasionally leaving me guessing or heading to Wikipedia. (Spitball artist? Everyday player? Batterymate?) Moving past the vocabulary, it was interesting to also learn about the Dead Ball Era, and the time Babe Ruth broke up a practice because he had hit all the balls out of the park to his fans waiting outside to whom he’d promised baseballs.

For history lovers

The book gives a glimpse into the political, social, and military history of the United States in the early decades of the last century and places the central baseball story in a broader context. Many of these are inserted within chapters, under the headings “Over There” for war front events, like how many soldiers died from the Spanish flu while aboard ships headed to Europe, and “Over Here” for information about the home front, such as the anti-German fervor that took place despite the fact that nearly 10 percent of the US population at that time were German immigrants and their American-born children.

Philadelphia’s historical narrative is too often dominated by its colonial era, so it was refreshing to shed light on a different facet of our past, read about so many local place names and long-gone stadiums, and picture shipyards populating the Delaware River from Bristol down to Wilmington.

What, When, Where

Work, Fight, or Play Ball: How Bethlehem Steel Helped Baseball's Stars Avoid World War I. By William Ecenbarger. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, February 2, 2024. 212 pages, hardcover; $25. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.