Picturing the people’s power

Woodmere Art Museum presents In the Moment: The Art & Photography of Harvey Finkle

For 50 years, with his little black Leica, Harvey Finkle has reminded society that “the homeless,” “the disabled,” and “immigrants” are living, breathing individuals deserving of respect. A retrospective of images by the social worker turned photojournalist is on view at Woodmere Art Museum.

In 1972, when activist folksinger Pete Seeger sang his objections about Richard Nixon at the President’s Pennsylvania re-election headquarters, Finkle and his camera were there. We see Seeger playing a banjo on a small platform, a man holding a mic up to the singer’s mouth. “For Finkle, as much as for Seeger,” notes explain, “art was a means of raising awareness, interrogating inequities, and inspiring political action.”

The Seeger photograph hangs among others depicting protest communication. Other sections in the exhibit, curated by art historian Antongiulio Sorgini, center on confrontations between demonstrators and authority and advocates’ use of images and symbols.

Fighting for those who had no one else

Finkle did not pick up a camera until his children were born, but family snapshots quickly evolved into social justice photography, first as an avocation, then full-time in 1972. Finkle covered groups fighting for those who had no one else to fight for them, including the Kensington Welfare Rights Union (KWRU), Project HOME, the Independent Living Movement, the Sanctuary Movement, AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP), and others. If there was a rally, blockade, march, strike, or demonstration in Philadelphia over the last 50 years, chances are good that Finkle and his camera were present.

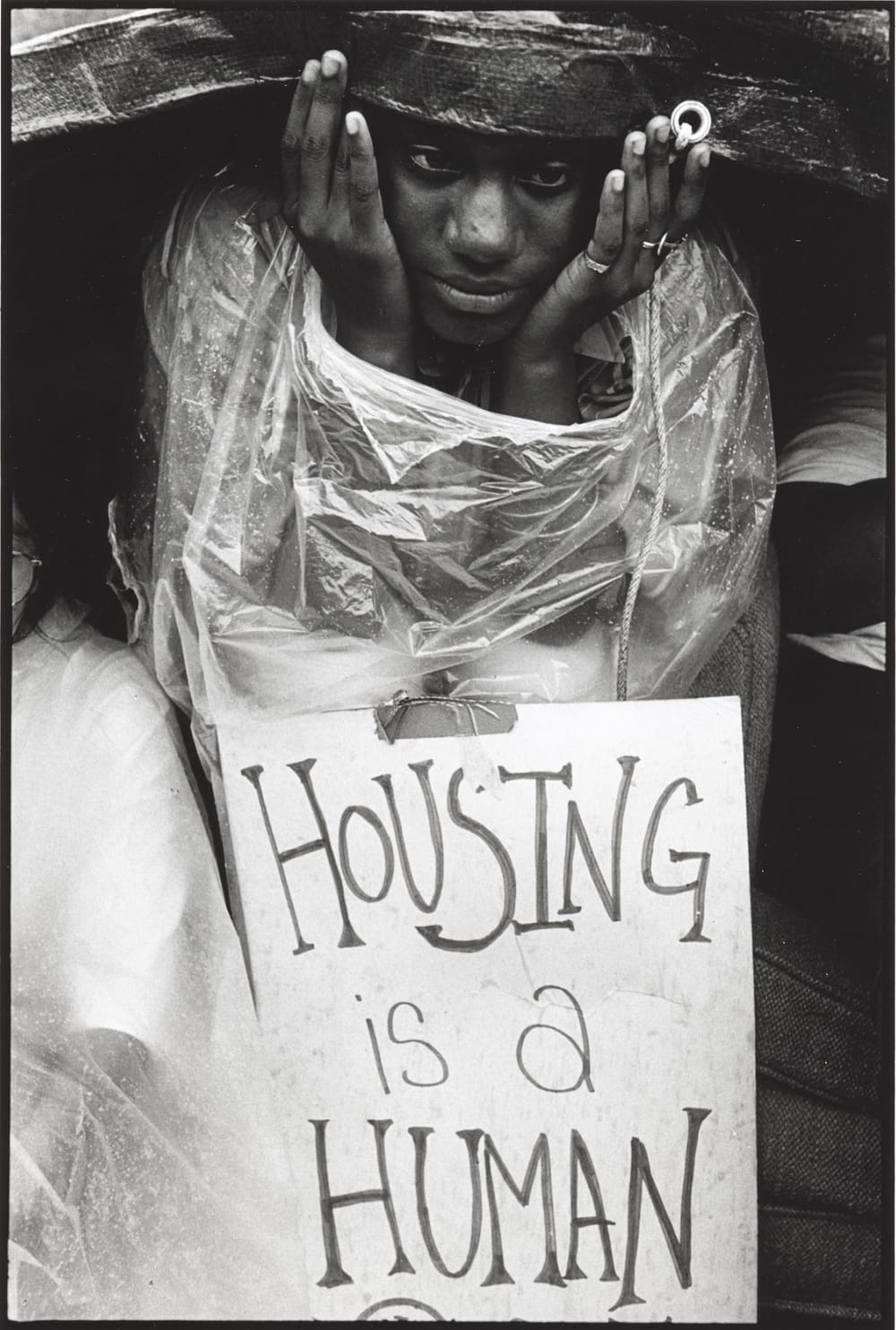

A photograph can eclipse time and space. Finkle’s pictures, some made decades ago, suit our current season of discontent. Consider his 1999 shot of a KWRU rally, of the Black woman sitting in the rain, plastic tarpaulins across her lap and over her head. Her face is a stoic mask. The sign at her knees declares: Housing is a Human Right.

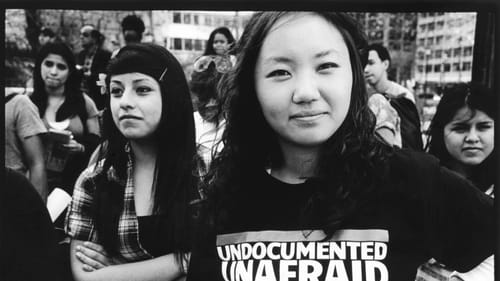

At a 2014 rally of Dreamers, Finkle waded into the sea of undocumented immigrants who’d been brought as children to the United States and found a teenage Asian girl. Smiling confidently at the camera, she stands hand on hip before Philadelphia’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) offices. Her t-shirt proclaims: Undocumented Unafraid Unapologetic.

In 1985, Disabled in Action staged a blockade on Chestnut Street, demanding better access to public transportation. Finkle’s photo shows a protester in a wheelchair with this sign: Paratransit Separate but Not Equal.

A lens for children

Words aren’t always necessary. In Indonesian Service in a Row House Mosque, Philadelphia (2002), four women in white chadors stand in soft focus, like snowy peaks, surrounding a small girl in the sharply focused center. The women’s heads are bowed and eyes closed, but the child’s eyes are wide, taking everything in.

Finkle’s lens is often trained on children, as if to tell anyone averse to his topics, “This is important, and here’s why.”

Deaf Olympics, 1989, a resonant image for the father of two grown children, was taken on an athletic track in bright sun. We see two pairs of feet standing close together and the crisp shadow of four hands, busily signing. “Both of my kids are deaf,” Finkle told Trey Popp of Penn Gazette last summer, noting the impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990). “When you look at what the world was like before they went to high school, and you see what it’s like now, it's incredible … Deaf people … have entitlements under the law—plus advances in technology.”

An empathetic artist

Finkle, 90, grew up in a Northeast Philadelphia family with roots in Russia and Poland. It took him a while to find his purpose, but it became clear while studying social work at the University of Pennsylvania and then working with the Pennsylvania Department of Public Assistance.

In Penn Gazette, Finkle described investigating reports of child endangerment: “You were going out to visit people who don’t want you to come into their home. … People knew there was a possibility of losing their kids. Our ambition was trying to help them remedy whatever the problem was and then help them keep their kids.” Finkle instinctively understood how the other person felt.

Close-up on humanity

Two depictions of protestors breaking into abandoned homes shuttered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) illustrate the impact of a vantage point. A 1996 image by Finkle of Cheryl Mucerino ripping boards from a front door was shot from the sidewalk. In 1995, he photographed Greg Rodriguez doing the same, but from inside the house, silhouetting the activist against the bright doorway. Shooting from inside, Finkle conveys the feeling of safety a shelter provides, underscoring the mantra of Project HOME cofounder Sr. Mary Scullion, “None of us are home until all of us are home.”

In another 1995 photograph, two squatters are trying to get some sleep. Finkle positioned his camera, and us, with them on the floor, makeshift pillows under their heads, a blanket pulled up to their chins. One of the trespassers, a young Black man, lies on his side and looks into the camera in exhaustion.

By putting his lens close enough for a conversation, Finkle draws viewers into an encounter, humanizing the people he photographs, forcing us to at least consider their concerns. Close up, we see differently.

He was there

Several themed books have grown from Finkle’s body of work, including Readers: Photographs by Harvey Finkle (1996), Urban Nomads: A Poor People’s Movement (1997), Still Home: Jews of South Philadelphia (2001), and Faces of Courage: Ten Years of Building Sanctuary (2021). The photographer has also assayed Philadelphia’s Mummers in offstage moments, exploring the subculture behind the flamboyant New Year’s performances.

In the Moment was inspired by Finkle’s gift of 100 images to Woodmere. The photographer’s prints, negatives, contact sheets, slides, research, and interview transcripts are archived at Penn’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts.

Wandering through the exhibition, you can’t help but hear the echo of Tom Joad, John Steinbeck’s hero of The Grapes of Wrath (1939) in Finkle’s images: “Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there.”

At top: Harvey Finkle’s 1999 photograph Economic Human Rights Campaign (Organized by Kensington Welfare Rights Union). (Image courtesy of Woodmere Art Museum.)

What, When, Where

In the Moment: The Art & Photography of Harvey Finkle. Through January 5, 2025, at Woodmere Art Museum, 9201 Germantown Avenue, Philadelphia. (215) 247-0476 or woodmereartmuseum.org.

Accessibility

Woodmere galleries are wheelchair-accessible, except for the Dorothy del Bueno balcony. Accessible parking is available near the Widener Studio building, to the right of the museum. Wheelchairs are available on request. For information and additional assistance, call (215) 247-0476 before visiting.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.