Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Remembering the dean of Philadelphia painting

Woodmere Art Museum presents Body Language: The Art of Larry Day

Larry Day (1921-1998) was as uncertain as any high school senior about his path. In his 1940 yearbook from Cheltenham High School, predictions ran toward music. Instead, Day became a painter and teacher, mentoring generations of artists at Philadelphia College of Art (now University of the Arts) and the University of Pennsylvania. In Body Language: The Art of Larry Day, Woodmere Art Museum examines his impact on American art.

From abstraction to representation

For most of his career, Day worked in figurative representation, painting places and people he encountered, including himself. He reworked classical compositions of masters such as Titian, Poussin, and Pollaiuolo, and inserted Renaissance elements into postmodern settings.

Briefly, though, Day was an abstract expressionist. Body Language includes Abstraction (1958), a canvas awash in soothing blue patches that fit together like leaves on a tree, and Journey (1956), with a more muted palette and vertical strokes.

According to exhibit curator David Bindman, professor emeritus of art history at London’s University College and Day’s close friend, even the abstract works “make open and explicit reference to vegetation in the form of undergrowth and bushes and sometimes figurative elements, always holding in balance free gestural brushwork and representational suggestions.”

Historical references and inquisitions

In the 1960s, Day turned to postmodern realism, foreshadowing Pop Art and Hyperrealism. The qualities for which he would become known are evident in the large 1967 work Narrative: To the Memory of Matteo Giovannetti, Day’s oblique commentary on the history and the cultural upheaval of the time in which he painted.

Giovanneti was a 14th-century painter known for religious frescoes, who pioneered architecture as a compositional tool. He painted in Avignon, France, then the Papal seat. Avignon’s palace and bridge haunt the background of Narrative, but the field is a cryptic contemporary scene of violence and expressionless onlookers. A man doubled over in pain is dragged by men in suits from a motorcycle parked in front of a studio. A young couple is perched on the back of the motorcycle. A middle-aged couple approaches. Inside the studio, a man in a dark suit surveys the scene, hands clasped behind his back. In the middle of it all, a man wearing sunglasses looks back at us, as if to ask, “What do you make of this?”

Day’s large, multi-person works repeatedly plunge viewers into ambiguous situations. Sometimes one character serves as an inquisitor, looking back. At others, several pairs of eyes return our gaze, as though we’ve just walked into the room.

In Picnic (Outing: Homage to Le Nain) (1970-75), seven people gather around a backyard table set only with glasses. Four look up expectantly—were we supposed to bring the food? Time after time, Day provides setting and characters, but the plot is up to us. “Here’s an artist who can really rope you into the conversations that he’s creating between figures,” noted Woodmere director William Valerio in a virtual conversation with artist Ruth Fine before the Washington Print Club. Fine, Day’s widow, concurred, “Larry very much believed that the work was completed by the viewer.”

Day’s approach to teaching was similarly evocative, according to former student and friend Bill White. In 2008, White, then a professor of art at Hollins University, curated a Day retrospective at the school and wrote, “He rarely gave you a simple yes or no response; more often to any question he replied with another question, acting as a painter’s Socrates. I always left my encounters with him with a deeper need to explore my own choices and considerations, to find my own way. Like all great teachers, Larry Day led us to our realizations and to our own aesthetic stance; he never told you what to do, as that would be short-changing our need to discover who we were and the necessity of our work as painters.”

Woodmere, the largest public holder of Day’s work, is one of three Philadelphia institutions recognizing the artist’s centenary. Partner exhibits, which closed earlier this fall, were presented at UArts’ Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery and Arcadia University.

After high school, Day served in World War II, participating in the battle for the island of Iwo Jima. Returning home, he entered Temple University and earned degrees in fine art and education. In 1953, Day joined Philadelphia College of Art, where he taught for the next 35 years. With the exception of military service and a decade in Washington, DC, Day spent his life in the Philadelphia area, living principally in Cheltenham Township.

Day brought an energetic intellect to the canvas. He read widely, wrote extensively, and thought deeply, with interests that ran toward philosophy, history, literature, architecture, and the significance of everyday events. According to the gallery text, “Day’s imagination was fueled as much by popular culture as by the discourses of contemporary philosophy.”

Let’s play

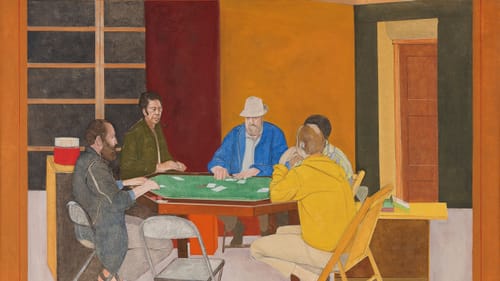

Games were a recurring motif. The Bridge Game (c. 1963), one of Day’s earliest figurative drawings, foreshadows The Poker Game (1970), which commemorates a monthly event in which the artist took part. In addition to exemplifying Day’s fascination with games as a narrative tool, Poker demonstrates his characteristic compositional reference to masterworks, in this case, The Card Players (1890-92) by Paul Cézanne.

Five friends sit at an octagonal table as the central figure, in blue, shuffles the cards. One folding chair—Day’s seat—is empty, as though he just stepped away to dash off this painting. The players’ attitudes and positions echo Cézanne’s group almost a century earlier. The poker game, which continues today, confirms Day’s belief that commonplace rituals anchor lives and strengthen bonds. For Day, Bindman wrote, “the ordinary in life is the source of all that is extraordinary.”

In addition to putting friends on canvas, Day frequently painted himself, and the best example is Day by Day (1991), which depicts the then-70-year-old artist painting himself at age six, in a pose taken directly from a family photograph.

The elder Day sits at an easel on a raised platform. The child stands below and in front of him. A low wall separates the two, like a time portal. The painting is strangely oriented—we observe the artist and setting from the side, but the child faces us, looking as he does in the photo. The elder Day’s view of his former self is incomplete, like a fading memory. Here, as in many works, Day assigns viewers the same task he gave students: draw your own conclusions.

What, When, Where

Body Language: The Art of Larry Day. Through January 23, 2022, at Woodmere Art Museum, 9201 Germantown Avenue, Philadelphia. $7-$10; free for members, children, and students with ID. (215) 247-0476 or woodmereartmuseum.org.

Adults 18 and older must show proof of vaccination or proof of a negative Covid-19 test within the past 72 hours. Children are only required to provide proof of vaccination or a negative Covid-19 test for events requiring close proximity over an extended time, such as concerts, lectures, and films, but not for museum entry or children’s classes, which are limited in size and maintain social distance. All visitors are required to wear masks in the museum and are encouraged to maintain social distance. Details and current procedures are available here.

Accessibility

All Woodmere galleries are accessible, with the exception of the Dorothy del Bueno balcony. Accessible parking is available near the Widener Studio building, to the right of the museum, separate from the main parking area. Wheelchairs are available on request. For information and additional assistance, call (215) 247-0476 prior to visiting.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.