Stunning photographs by formerly incarcerated men of color

TILT Institute for the Contemporary Image presents Wherever There Is Light

Near the start of the TILT Institute’s new exhibition, Wherever There Is Light, a stunning and introspective collection of photographs by formerly incarcerated men of color, is a self-portrait remarkable not for what it discloses but for what it conceals.

Jonathan Chiu—part of a Los Angeles cohort that worked with lead artist Larry W. Cook, who founded Wherever There Is Light as an evolving workshop series and artist network—has his back to the camera, his black shirt melding into the photograph’s dark background.

To Chiu’s left are six identity cards, among them a California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) Religious Diet Card, a CDCR inmate ID, and a “privilege” card, each carrying a stamp-sized mug shot.

But in the portrait, Chiu’s face is turned away; we see his close-cut hair, a jawline scruff, a hand curled to his chin. The image says: you can ID me, you can give me a number, but you cannot fully capture me. The artist’s power—as both photographer and subject—is his ability to decide what the viewer can see and know.

Agency and changing conversations

That sense of agency undergirds Wherever There Is Light, which features the work of four artists, two of whom found their passion for photography and art through Mural Arts Philadelphia’s restorative justice program while they were incarcerated at Graterford Prison (now SCI Phoenix).

The exhibition, which includes portraits, self-portraits, landscapes, and collage, changes the conversation about imprisonment, identity, and justice by putting formerly incarcerated folks on the other side of the camera. Typically, they are the ones being viewed through the lenses of others—judges, journalists, the general public—lenses warped by racism, classism, and misapprehensions about who ends up in jail and why.

Blues, reflection, and a king

Wherever There Is Light lets the artists speak for themselves. Akeil Robertson, part of the Philadelphia cohort that worked with Cook in 2023-24, photographed “blues”—what inmates in county jail called their uniforms—encased in plastic dry-cleaner bags and hanging from trees.

The clothes—light-blue scrub tops and darker pants—disembodied and wind-blown, dangling from branches and fences, evoke lynchings and histories of erasure. The empty garments are fragile and haunting, cerulean ghosts reminding us of all the people we pretend not to see.

According to the City of Philadelphia’s July 2024 prison population report, more than 4,800 people are currently incarcerated in the city; 90 percent of them are people of color. Don O. Jones, another of the Philly artists in the exhibition, used his camera to document one of them, former inmate (and longtime friend) Terrell Woolfolk, an author and anti-violence advocate who was released from prison in July 2022.

The series shows Woolfolk on city streets, in front of a rowhouse, posing before a brightly painted anti-violence mural, his gaze sober and reflective. One photograph is titled Looking Toward the Future, But Thinking of the Past.

Those words aptly describe the work of Vernon Ray, who arranged self-portraits in a pattern along with framed photographs of solid black and solid white, creating a chessboard-style grid. Some of the photos were shot on his iPhone while traveling to West Africa, a trip that, he noted to his cohort, carried intense emotional weight.

In one of the images, Ray holds a chess piece—the photo is titled A King Is What I See—while looking intently into a mirror. The work speaks of strategy and regret, choices and missed opportunities, destiny and self-regard. It asks: Who am I? Who might I become?

Beyond the IDs

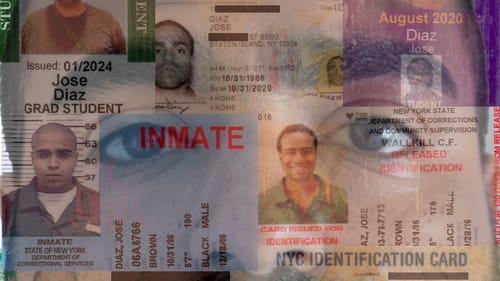

José Díaz poses similar questions in his collages, which layer portraits with childhood photos, family images, identification cards, and journal excerpts, evoking the complexity of any individual and the impossibility of “knowing” someone from a single image.

One collage includes the hand-written words, “I always felt like a stranger to myself—a foreigner within my own skin.” Another stacks translucent childhood photos, some tipped on their sides, with current portraits, as if to say, “Yes, the bearded man in the knit ski cap was once that wide-eyed boy in a crisp bow tie … Yes, every person behind bars is someone’s child.”

A short video includes interviews with some of the artists; in it, Díaz talks about his desire to create a photographic portrait that conveys emotion. Two pieces, The State of Me and Beyond the State of Me, do exactly that: ID cards from universities and the corrections system, collaged around and over the artist’s face, evoke both state-sponsored entrapment and the individual’s resilience, his resolute expression still legible through the thicket of “official” images and numbers.

No walls

Lead artist Cook widens his lens to examine landscape in contrast to the confinement and privations of prison life. He superimposes outdoor photographs onto the cutout figures of individuals so it appears that a prairie, a canyon, or a cityscape is literally coursing through their bodies.

These images invert the idea of a person imprisoned in a hostile environment. In Cook’s photographs, humans and the outside world merge. The self contains grandeur and beauty; the only limits are the far reach of our imaginations.

One of the largest photographs in the show is the final one, untitled, by Cook: a man in all-white—pristine sneakers, sleeveless undershirt, jog pants—with tattoos and cornrowed hair, crouches on a beach, facing the ocean. Around him is a wide apron of sand, then sea, then sky. He’s looking not at us but toward the horizon line. We can only imagine what he’s thinking. There are no walls.

On Thursday, November 14, TILT will offer a day of associated signings, screenings, and panel discussions at TILT and Icebox Project Space. More information can be found on the TILT website.

At top: Photographer Vernon Ray’s A King Is What I See. (Image courtesy of TILT.)

What, When, Where

Wherever There Is Light. Through December 21, 2024, at TILT Institute for the Contemporary Image, 1400 N American Street, Suite 103, Philadelphia. (215) 232-5678 or tiltinstitute.org.

Accessibility

TILT is a wheelchair-accessible venue. Ramp access to the main gallery is on the first floor. Call (215) 232-5678 during business hours, and a staffer will meet you and open the doors.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman