Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Reconstructing a Legacy

University of Pennsylvania presents Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect

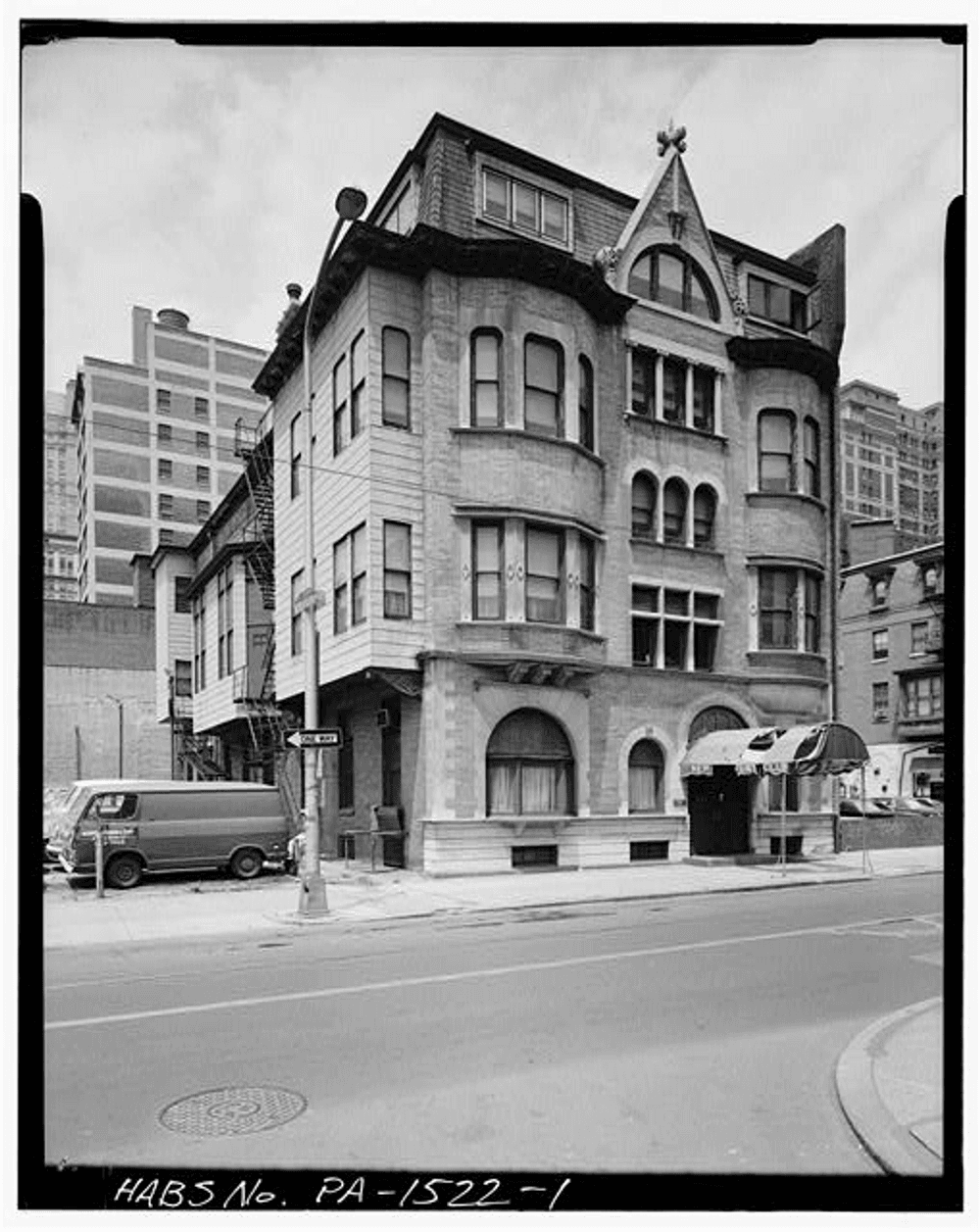

The New Century Club was where influential Philadelphia women developed a civic presence and political voice, where they changed ideas about what women could be, do, and achieve. Fittingly, their 124 South 12th Street headquarters was designed by the first woman in the United States to establish an independent architectural practice: Minerva Parker Nichols (1862-1949). The stately building disappeared decades ago, and its architect would have suffered the same fate, save for a diligent architectural historian, whose exhibit Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect, is on view at the University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives.

From historic to … history

The New Century Club was razed in 1973 for a parking lot, its destruction approved by the Philadelphia Historical Commission, which eight years earlier had declared the building a landmark. With it went significant visual evidence of Nichols, who in 1893 was prominent enough to have been among 11 Philadelphia architects—and the only woman—quoted in a Philadelphia Times article on the design impact of that year’s World Columbian Exposition.

Despite a national reputation, designing at least 80 projects, and writing for professional and popular publications, Nichols’s work would evaporate to a faint trail of demolished buildings, unbuilt plans, and a handful of extant structures hiding in plain sight. Her name almost vanished from architectural history.

Architectural historian and preservation planner Molly Lester discovered Nichols as a UPenn graduate student, and the exhibition results from her decade of detective work. Documents and images Lester uncovered are augmented by new large-format contact prints by Elizabeth Felicella of Nichols’s remaining buildings, many in and around Philadelphia, where her practice centered. They stand in Mt. Airy, Germantown, and the Northeast, and in Main Line communities that sprouted along the Pennsylvania Railroad: Bryn Mawr, Gladwyne, Wayne, and Radnor. Lester and Felicella’s goal is “to create an archive in the absence of one,” to reconstruct the entire portfolio, reestablish Nichols’s legacy, and introduce her to new generations. The research is ongoing.

Residential specialist

Nichols was born in Glasford, Illinois, to a Civil War widow and learned to draw from her maternal grandfather, a housebuilder. She and her older sister Adelaide moved with their mother in 1876 to Philadelphia, where Nichols became a governess to help with expenses. She also completed programs in technical drawing at Philadelphia Normal School (1882) and the Franklin Institute Drawing School (1886), after which she apprenticed with Edwin W. Thorne. Nichols provided the design training he lacked, and from him learned how an architectural practice functioned.

When Thorne sought larger quarters in 1889, Nichols, then 26, opted to remain in independent practice at 14 South Broad Street. A photograph from 1891, the year she married Unitarian minister William Nichols, shows her leaning over a drafting table, back to the camera, clad in a floor-length mutton-sleeve dress.

Believing architects should specialize, she selected residential design—a smart choice, given suburban expansion. With Thorne, she’d drawn plans for Rutledge, a Delaware County settlement targeted to workingmen, and she continued to pursue speculative clients, including Overbrook Land Improvement Company.

Nichols was convinced that women brought useful perspective to home design because so much of their work took place at home. For well-to-do clients, that involved household staffs, which added to design considerations. Nichols questioned clients extensively and planned for their specific needs. For parents with small children, she made life more convenient by shortening staircase risers, connecting bedrooms with doors, and leaving bookcases open for accessibility.

Thoughtful, hands-on design

Though she lacked society and Ivy League connections, Nichols built a network of patrons, artisans, and builders, many of them women. She was known to supervise projects onsite and to specify the finest materials and workmanship, which earned her the respect of clients and peers.

Mill-Rae (1890-91) the home Nichols designed for Rachel Foster Avery in Northeast Philadelphia (now a spiritual retreat, Cranaleith) may have brought her to the attention of the New Century Club, where Avery was a member. Nichols also designed Wilmington’s New Century Club, which now houses Delaware Children’s Theatre.

Though Nichols’s buildings are not streamlined by contemporary standards, she planned for simplicity and utility. Proportions are generous. Porches are deep, windows admit plenty of light, and stairways wind gracefully. From handrails to electric lights, fixtures and fittings are elegant but not fussy. These were inviting, comfortable, easy-to-care-for structures.

A truncated career

The exhibit mentions a few industrial designs, such as Eagle Iron Foundry in Nicetown and a macaroni factory in South Philadelphia, but homes are foremost in Nichols’s portfolio.

Among those still standing are homes in Mt. Airy designed for Mary Potts (1890) and her sister and brother-in-law, Harriet Potts Taylor and Edwin Taylor, and elsewhere in Philadelphia unusual twin homes for suffragist sisters Sara Jane and Mary A. Campbell. Those homes, oriented back-to-front rather than side-by-side, appear to be a single dwelling.

The professional portion of Nichols’s career ended in 1896, when the family relocated to Brooklyn for Rev. Nichols’s work. Separated from her client base, Nichols continued designing homes for family and friends, including Westport, Connecticut, dwellings for herself (Rev. Nichols died in 1917), and for Adelaide Nichols Baker and Jack Baker, her daughter and son-in-law. Nichols continued to write and speak on meaningful design, and became an advocate for improved housing and day nurseries for working families.

Who, and what, is missing?

The exhibit reminds us that the public record is often incomplete. Was Minerva Parker Nichols forgotten because she was a woman? Because she designed homes instead of skyscrapers? Because her career was limited by family obligations? Or is it that Philadelphia has a habit of tearing down historic buildings?

History is only as accurate, as thorough, as the information at hand, and careful readers need to consider what and who is missing. Will the archives being compiled today offer a more complete view, or will it be easier, in a virtual world, for perspectives to vanish in a keystroke? Who will be diligent and clever enough in the future to rediscover what’s being overlooked in the present?

Above: The New Century Club, designed by Nichols in 1891-21, and torn down in 1973 to make way for a parking lot. (Photo courtesy of the Historic American Buildings Survey and University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives.)

What, When, Where

Minerva Parker Nichols: The Search for a Forgotten Architect. Through July 22, 2023, at University of Pennsylvania Architectural Archives, Harvey & Irwin Kroiz Gallery, 220 South 34th Street, Philadelphia. (215) 898-8323 or design.upenn.edu.

Accessibility

The wheelchair-accessible entrance to the Architectural Archives is through the Duhring Wing, on the building’s south side opposite Irvine Auditorium. To access the entrance, please call (215) 898-8323 in advance.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.