Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

A precedent for presidents

The Rosenbach presents Succession: Why Presidential History Matters Now

Here we are again. On the precipice of what will be one of the most consequential presidential elections in American history, the Rosenbach Museum & Library presents Succession: Why Presidential History Matters Now.

Given that we’ve watched the hallmark of American democracy—the peaceful transfer of power—fall into doubt, can history offer anything in the way of guidance? Succession promises to change the way we think about the executive office. Don’t we do that already, considering that the “unprecedented” has become precedent for all three branches of government? What’s needed is reassurance, and Succession provides that.

A letter from Washington

The exhibit grew from the collection of David Rosenbach Sackey (1938-2017), a grand-nephew of Rosenbach founder Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach. When Sackey celebrated his Bar Mitzvah, his grand-uncle presented him with a letter George Washington wrote in May 1799. The handwritten letter, mounted with an image of Mount Vernon, where it was composed, set Sackey on a lifetime of collecting. Succession is drawn from Sackey’s trove of Americana, supplemented by the Rosenbach’s presidential holdings.

If relinquishing power is a democratic hallmark, Washington is its champion. Not only did he resign as commander of the Continental Army after independence was won, he willingly left the presidency in 1797. A handwritten transcript of Washington’s 1783 farewell to Congress is on view.

Held in awe by many Americans of his time, Washington probably could have remained president (yet the 22nd Amendment, limiting US presidents to two terms, was ratified in 1951). But he voluntarily turned things over to his duly elected replacement, setting the standard for every successor who survived to the end of his term in office … except one.

Independence and enslavement

Though exemplary in some ways, Washington was flawed. He enslaved Black people for most of his life, yet so admired the verse of formerly enslaved poet Phillis Wheatley that while commanding the Continental Army, he invited her to visit. A copy of Wheatley’s Poems on various subjects, religious and moral (1773), written before she gained freedom, is on display.

Several documents reveal the equally paradoxical Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence and third President. In a 1791 letter, written as the Constitution was being amended, Jefferson suggested that the Bill of Rights include the “right of personal freedom.” Inches from those sentiments sit two inventories, written in Jefferson’s small, neat hand, of 75 enslaved persons who maintained two of his plantations, Tomahawk and Bear Creek.

Concerns then and now

Familiar issues echo through the letters of second President John Adams, a tireless correspondent whose tart missives pepper the exhibition. A February 1776 observation sounds lamentably fresh: “You will find no instance of a Republic conquered by Monarchy, by arms, nor any other way but by Corruption and Division.” Adams’s worries about the threat posed by factions were shared by many in the founding generation.

During his assassination-shortened presidency (1843-1901), William McKinley was concerned about tariffs to protect American manufacturers (he was for them), Congressional gerrymandering (against), and increasing electoral participation, especially among Black voters (for).

From sojourn to way of life

The founders envisioned that people would hold office for a time and then return to their fields, law books, or printing presses. Though delegates to the Continental Congresses and Constitutional Convention were exclusively white, male, wealthy, and better educated than other citizens, they came from varied walks of life.

As the nation grew, politics became a professional pursuit and, for some, a lifetime endeavor. Pressure to win reelection increased, leading representatives to amend positions to accommodate what was popular and not necessarily best for the country. Electronic and social media have intensified this tendency, with expediency often diluting principle.

Though presidents are now term-limited, they too are subject to these forces, as gallery text explains: “In the early 21st century, we observe polarized politics eroding the mystique of the presidency—which is, in fact, an important part of the president’s power, at home and around the world.”

Words by Washington, Lincoln, and Truman

Set in hushed, necessarily low-lit galleries, the exhibit provides the perfect environment for quiet thinking, not to mention a relief from 21st-century political discourse. Explanatory signage helps decipher manuscripts which, though beautiful and remarkably preserved, are fragile and faded with age.

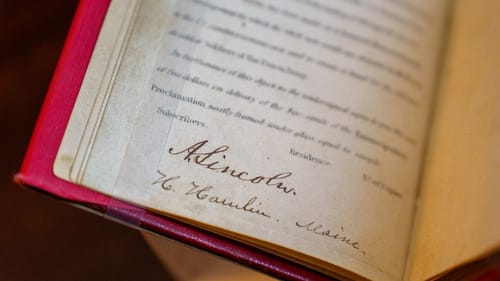

Though original documents can be challenging, it’s thrilling when a word jumps off the page, as with Washington’s boldly printed “Confidential” across the top of a 1789 letter to James Madison, then Speaker of the House. And you can almost hear Abraham Lincoln delivering the final words of his last message to Congress in December 1864: “In stating a simple condition of peace, I mean simply to say that the war will cease on the part of the government, whenever it shall have ceased on the part of those who began it.”

Typewritten papers from more recent presidents are easier to read. Harry Truman probably dictated the succinct 1970 note he sent to Sackey. By then, Truman was 85 and maintaining an active post-presidency. An inveterate walker, he sounds in a hurry to get out the door: “The duties of a President are so vast, demanding and unrelenting, that he cannot stop to reflect upon events that pass into history. Sincerely yours, Harry Truman.”

Presidential and human

While revealing the rarefied experience of being president, the exhibit also shows the chief executives as people.

Marvel at McKinley’s impeccable law-school notebook, with not a doodle in sight. Or sympathize with Ulysses Grant, whose purported problems with alcohol, desire to expand presidential power, and poor decision-making were fodder for a pamphlet of mocking cartoons, Ulysses the great, or Funny scenes at the White House (1875).

As trains connected the continent, rare photographs contrast the whistle-stop styles of Theodore Roosevelt and his successor, William Howard Taft. Roosevelt lunges over the caboose railing as though ready to launch himself into the rapt crowd, while Taft, a large man, poses stiffly in a crowd jammed onto the tiny caboose platform. He looks like he can’t wait to depart.

Though Succession may not produce a greater sense of calm as 2024 approaches, it confirms the nation has survived difficult presidencies and periods. Viewers will have to take reassurance from that and hope for the best.

What, When, Where

Succession: Why Presidential History Matters Now. Through November 26, 2023, at the Rosenbach Museum and Library, 2008-2010 Delancey Place, Philadelphia. (215) 732-1600 or rosenbach.org.

Accessibility

The Rosenbach is wheelchair-accessible at its south entrance. Please call (215) 732-1600, Ext. 0 for assistance.

Complimentary admission is provided to government-funded Personal Care Assistants (PCAs) accompanying visitors requiring their assistance. For information and to request a ticket for a PCA, please contact the Rosenbach at [email protected].

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.