Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The authors of democracy

The National Constitution Center presents its new First Amendment Gallery

In its new First Amendment Gallery, the National Constitution Center (NCC) explores the evolution of Americans’ most cherished rights. Shaped like an open hand, the exhibit devotes sections to freedom of speech, press, religion, assembly, and petition. Steps away, inscribed in marble, is the center’s massive First Amendment tablet, bearing the 45 words that guarantee citizens’ ability to think and express themselves freely and, in so doing, strengthen democracy.

The exhibit brings the practical impact of those words to life through legal decisions, artifacts, and video interviews with key figures. Interactive tools put visitors in the shoes of those who’ve tested, defended, and determined what the promise of free speech, press, religion, assembly, and petition means and has meant since the First Amendment was ratified in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights.

Speech: more is better

Free speech may be America’s calling card, but it’s not unlimited. First Amendment protections apply only to government entities, and though content generally can’t be restricted by the government, the time, place, and manner might be. For example, periods of national tension, such as wartime, have often caused greater restriction of speech.

In 1965, eighth-grader Mary Beth Tinker protested the Vietnam War at school by wearing an armband. She was suspended. Her parents sued and, aided by the American Civil Liberties Union, were vindicated in the Supreme Court with Justice Abe Fortas writing that neither students nor teachers “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” (Tinker v. Des Moines, 1969). Tinker, now retired and an enthusiastic student-rights advocate, spoke in September at a virtual NCC town hall marking Constitution Day.

Displayed near the armband is Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis’s draft opinion in Whitney v. California (1926), which upheld a conviction for remarks made at a Communist Labor Party meeting. Though Brandeis concurred, he expressed what became the modern foundation of free speech, that it should be allowed "unless intended and likely to cause imminent and serious injury."

NCC president and CEO Jeffrey Rosen quoted Brandeis at the 2022 installation of the First Amendment tablet: “If there be time to expose through discussion the falsehood and fallacies, to avert the evil by the processes of education, the remedy to be applied is more speech, not enforced silence. Only an emergency can justify repression.”

Press: rights with responsibility

Visitors can weigh in on landmark Supreme Court decisions related to press freedom, including prior restraint of publication (Near v. Minnesota, 1931), compelling reporters to disclose confidential sources (Branzberg v. Hayes, 1972), restraining publication of a school newspaper (Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 1988), and holding journalists liable for statements about public officials (New York Times Company v. Sullivan, 1964).

Sullivan is one of two decisions involving the New York Times considered pillars of journalistic freedom. It established the "actual malice standard" for coverage of public persons, in which the court said that inaccurate damaging statements can’t be considered libelous unless made with knowledge they were false or with reckless disregard for the truth.

In New York Times Company v. United States (1971), better known as the Pentagon Papers decision, the court prevented the Nixon Administration from halting publication of leaked classified documents about the Vietnam War, affirming that newspapers had a broad right to publish information critical of the government. The front page of the June 15, 1971 Times, carrying the series’ third installment, is on view.

Religion: let us pray … or not

Freedom of religion is protected by two clauses: Free Exercise permits individuals to believe or not, and Establishment forbids the government from favoring one religion over another or over no religion.

While belief is protected, religious conduct may be regulated. Individuals have the right to request exemptions from restrictions or obligations they feel are unjust, such as military service.

During ratification, those who had fled religious persecution were concerned that the right to worship would be curtailed. On view is a 1789 handwritten letter in which George Washington assures a community of Quakers that all Americans will have the right to believe as their consciences dictate.

Science and religion have often come into conflict, particularly in public school classrooms. The primacy of science was famously challenged in Scopes v. State (1925) when a high-school teacher was found guilty of teaching evolution in violation of Tennessee law. A copy of the 1914 textbook John Scopes used is on view. Recent science-religion clashes have involved the teaching of intelligent design as an alternative to evolution.

Assembly and petition: meet, march, and sign

Though fewer blockbuster decisions have involved the rights of assembly and petition, they are no less essential to healthy democracies. Had colonists’ petitions not gone unanswered by the British government, and had colonists not assembled to discuss and build consensus for independence, there would have been no new nation in which to enshrine those rights.

Assembly enables groups to gather in public, a critical right for the less powerful. Farm laborers, civil-rights demonstrators, and women demanding equality all needed to assemble to create awareness and support among the broad population. As with speech, the government can restrict the time, place, and manner of gatherings. The exhibit includes memorabilia for and against the Equal Rights Amendment, the focus of numerous assemblies and petitions, which still has not achieved ratification.

Closely aligned with assembly, petition enables people to bring wrongs to official attention and to seek redress. It’s been instrumental in shaping a more just society by holding the government to account for policies and practices that injure individuals and groups. On view is an 1884 petition made on behalf of the indigenous Paiute tribe, requesting that its members be returned to Oregon lands promised to them by the government.

We the authors

In September, the NCC partnered with national free speech organizations to host a National First Amendment Summit to examine increasing threats to freedom of expression. During the event, author Salman Rushdie, interviewed virtually by PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel, shared that the First Amendment was one of the reasons he chose to settle in the United States. Rushdie, who was brutally stabbed last year in an attack at the Chautauqua Institution, acknowledged concern about the rise of authoritarianism and the devaluation of truth. Still, he reminded listeners, “It’s necessary for us to understand that we must allow the speech of those we don’t like.”

In 45 elegant words, the First Amendment poses thorny questions that have occupied a nation for 232 years. If the words are democracy’s headline, the reams of argument and interpretation are its text. We’re the authors, and the writing continues.

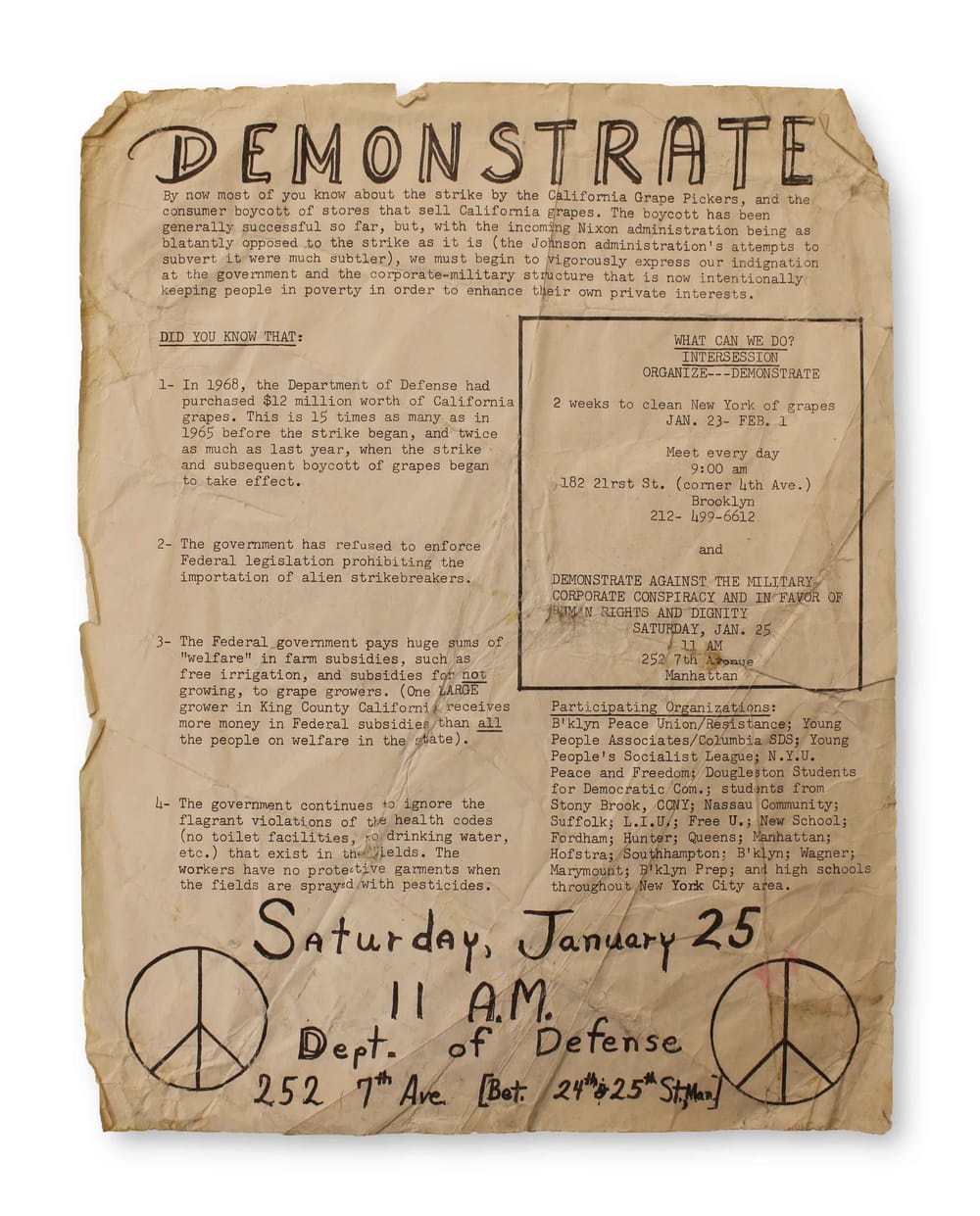

At top: This flyer (c. 1969) advertises a demonstration supporting the Delano Grape Strike, a labor strike led predominately by Mexican and Filipino grape pickers in Delano, California. (Image courtesy of the National Constitution Center.)

What, When, Where

The First Amendment. National Constitution Center, 525 Arch Street, Philadelphia. (215) 409-6600 or constitutioncenter.org.

Accessibility

The National Constitution Center is committed to making its facilities, exhibits, and programs accessible for all audiences. All entrances and spaces are wheelchair accessible, and the NCC garage provides spaces for visitors with disabilities. Accessible restrooms and family/gender-neutral restrooms are available. For more information, see the NCC's accessibility page or contact the center at (215) 409-6700 or [email protected].

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.