Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Exhuming the past, examining the future

The Mütter Museum presents its Postmortem Project exhibition

Mütter Museum is taking a hard look in the mirror, and wants the public’s help. Last October, the medical history museum initiated a two-year process to reconsider the presentation of its collection, which includes about 6,600 human specimens. The Postmortem Project exhibition will expand as the process continues.

The museum was established in 1863 by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia (CPP) and overseen by the CPP board, and the human remains it holds were often obtained under unacceptable conditions, without consent, and are still, in some instances, displayed in styles inconsistent with contemporary presentation standards.

Assessing the feelings of multiple groups is central to the examination and will shape the Mütter’s future. But the anticipated realignment of content consistent with contemporary sensibilities, while ensuring that stories of medicine and public health continue to be shared through historic objects and biological specimens, has unleashed strong emotions. It’s to the Mütter’s credit that issues are being met head-on with considerable transparency.

A question of consent

Permission and provenance are key concerns, as Mütter executive director Kate Quinn explained to WHYY’s Alan Yu: “How did these materials come into our collection? How are they in our possession today? Who consented to be on display? Did they? Do we have the paperwork in place? We can’t ignore these questions today. That work was happening prior to my arrival.” Quinn joined the museum in 2022 and has served as executive director of Michener Art Museum and director of exhibitions at Penn Museum.

Focus groups and open houses began last fall, but the project’s public phase really started in spring of 2023 when hundreds of the Mütter’s popular videos and online exhibits were suddenly removed from digital platforms, sparking controversy. After review, many videos were restored, and in August 2023, online exhibits were replaced by a searchable digital database, which advises users: “Our records may include historic language that is inaccurate, offensive, or inappropriate. We are committed to acknowledging and updating hurtful legacies in the collections in our care. We welcome your feedback in identifying harmful language or images as we continue to update our database.”

Popular exhibits remain, for now

Entering the Mütter’s upper gallery makes clear the need for a reset. Near the doorway rests a coffin-shaped vitrine containing the remains of a woman whose body, after death, turned to adipocere, a waxy organic substance. The period sign introduces her as “The Soap Lady,” signaling the macabre-bordering-on-flippant tone for which the museum has sometimes been known.

On the far wall is a congress of human crania: anatomist Joseph Hyrtl’s skull collection. Gathered in the mid-19th century to disprove racist theories, they came from persons who, as April White wrote on Atlas Obscura in 2021, “were not, by law, given bodily autonomy, such as those who died of suicide, were executed, or died in a workhouse.”

Context, not excuses

The Postmortem Project unflinchingly describes the collection and how it grew. It’s worth noting that the Mütter did not fully open to the public until 1976. At its founding, specimens were intended for the medical community.

A timeline offers perspective on institutional, medical, and world history. The years 1860 to 1880 were a time of rapid acquisition. Though records were kept, they lack details now legally, medically, and ethically required.

Despite those shortcomings, much of the core collection remains on view, including a full-body plaster cast and preserved livers of conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker. The famous twins’ livers were obtained when they were autopsied at CPP in 1874. College fellows obtained family permission after the fact.

Unlike the twins, most specimens came from the anonymous poor. Tag names likely belong to acquiring physicians. For example, it’s known the remains of the woman in the vitrine were purchased by Dr. Joseph Leidy for $7.50, but not who she was.

Donating one’s body to science after death was unheard of before the 1950s. To obtain cadavers, early anatomy instructors dispatched students to the nearest indigent cemetery. In 1883, Pennsylvania’s Anatomy Act stemmed graverobbing and provided cover for physicians by legalizing the distribution of cadavers for medical study. The law was written by CPP Fellow William Forbes, convicted of graverobbing at Lebanon Cemetery for Jefferson Medical College. The act did nothing to guard indigent rights.

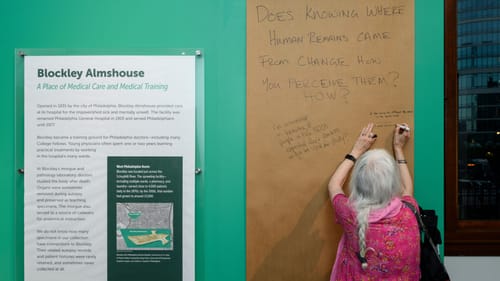

The Blockley connection

Blockley Almshouse looms large in the Mütter story because it’s where many specimens originated. Founded in 1834, Blockley included a hospital, indigent housing, a workhouse, and an asylum for the mentally ill. (It became Philadelphia General Hospital in 1902, evolved into a respected public hospital, and closed in 1977.)

Blockley was more crowded and more scantily supplied than private hospitals, with some patients providing labor in exchange for care. The dying likely couldn’t afford burial and may have had no one to claim them. Specimens and cadavers from Blockley’s pathology lab and morgue were often procured, without patient consent, as teaching tools.

Tough questions

“How does knowing where human remains came from change how you perceive them?” challenges a large sheet of paper on one wall. One visitor wrote, “It doesn’t. I look to what was learned in the past and what can be learned in the future…” Another disagreed: “It makes me question the previous living conditions of the deceased and whether their history is being respected.”

Provocative inquiries confront visitors at every turn. “Has racial bias impacted your medical care?” asks another poster-sized sheet near materials related to Dr. John Marion Sims. Sims, known for developing mid-19th-century surgical treatments for childbirth injuries, achieved advancements by experimenting without anesthesia on enslaved women. A prevalent racist belief of the time held that Black people felt pain less acutely than others.

In presenting unpleasant facts and asking hard questions of as many people as possible, the Mütter will offer new perspectives on the collection, according to the project’s lead community engagement consultant, Monica O. Montgomery. The museum wants to “engage the public about how to tell the stories … many of which touch on difficult issues such as provenance … and race and issues of what constitutes consent.”

“Is it legal? Is it ethical? Is it just?”

CPP and the Mütter are not alone in coming to terms with the past. On view are newly rewritten policies from the British Museum (2018), the University of Glasgow (2023), Harvard University (2022), and Penn Museum (2023). Visitors are invited to write directly on the documents, which sit beneath the query: “Is it Legal? Is it Ethical? Is it Just?” To which one writer replied: “If they consent.”

What might the reconstituted Mütter look like? Will it retain appeal for longtime fans and attract new viewers? Can it preserve something of its essential character while reckoning with its past? Time will tell. Right now, the Mütter’s only option is to keep going.

What, When, Where

Postmortem Project. Through 2024 at the Mütter Museum and Historical Medical Library, 19 South 22nd Street, Philadelphia. (215) 563-3737 or müttermuseum.org.

Accessibility

Mütter Museum has a wheelchair-accessible entrance on Van Pelt Street directly behind the museum; visitors can request assistance by using the intercom. Wheelchair-accessible restrooms are located on the second floor; visitor services associates can provide elevator access. More information is available here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.