Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

An Orthodox teen in a wider world

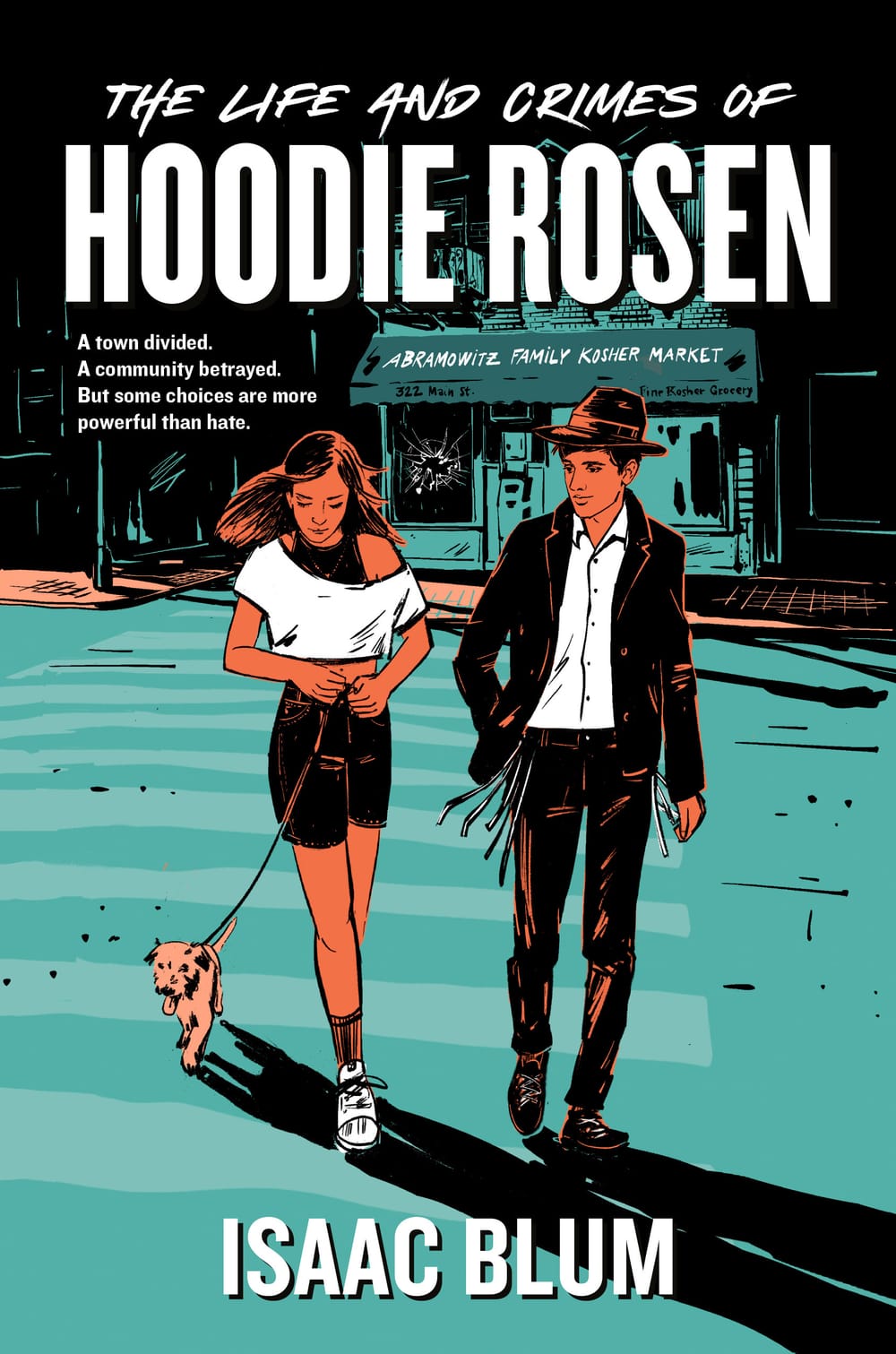

The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen, by Isaac Blum

When you pick up The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen—which you should—don’t be fooled by the noir-ish cover (blue-black shadows, a street empty but for two teenagers and a small dog) or its 18th-century-esque, tongue-in-cheek chapter subtitles (“In which we discuss livestock and the differentiation therebetween … In which I have forbidden thoughts about slow-cooked chicken.”)

Don’t be fooled, because Philadelphia writer and educator Isaac Blum has written a thoroughly up-to-the-minute YA novel, more nuanced than noir, a book whose soul beats steadily through the sarcasm of its main character.

That character is the titular Yehuda Rosen, known as Hoodie—the 15-year-old only son (he has five sisters) of an Orthodox family that has recently relocated, along with others from their former community, to a small town outside of New York. And in this town, residents are not thrilled with the influx of Jews.

Hoodie’s world

Lawn signs spring up: “Protect Tregaron’s Character.” The town council holds a late-night meeting to change the zoning laws and prevent Hoodie’s father, a developer, from building a high-rise for more Orthodox families. There is a ripple of antisemitism that begins quietly and rises to violent heights.

“[The locals] talked about us like we were an invading army, like we were going to ride in on horseback with torches and pitchforks, to set their buildings on fire and slaughter them kosher-style,” Hoodie observes with a characteristic mix of truth-telling and hyperbole.

Of course, because this is a YA novel, and because Blum is knowingly tipping his Borsalino (the fedora-like hat Hoodie wears) to every star-crossed love story you’ve ever read, Hoodie finds himself becoming friends (more than friends?) with Anna-Marie Diaz-O’Leary, who is not only a shiksa (non-Jew, in the parlance of his people) but the daughter of the town’s mayor, Monica Diaz-O’Leary, who is leading the charge against the incoming Orthodox.

In Hoodie’s world, even a platonic afternoon with Anna-Marie—a first date that consists of erasing antisemitic graffiti from Jewish gravestones in the local cemetery—violates his community’s rules. Word gets around fast—it’s a small town, and everyone is watching—and the rabbi at Hoodie’s yeshiva reprimands him for even thinking about Anna-Marie.

“I understood what he was saying,” Hoodie thinks after the rabbi’s tirade, “My friendship with Anna-Marie, the enemy, would keep me from Torah, and I couldn’t fight antisemitism with a gentile. Except that was what I’d just done when we removed the paint.”

“A walking bar mitzvah”

Blum, who has taught English at Orthodox Jewish and public schools, knows this world intimately—well enough to render it in all dimensions, dodging stereotypes in favor of specificity and, on Hoodie’s part, a wry, growing awareness of just how different his people are in the eyes of non-Jews, including Anna-Marie.

In the second chapter (subtitle: “In which I introduce you to my family”), Hoodie speaks (another 18th-century novelistic convention Blum plays with delightfully) directly to the reader: “You may have pictured me in your mind. If you’re going by grossly exaggerated Jewish stereotypes, then you’re spot-on. Mazel tov. I’m a walking bar mitzvah: dark curly hair and a rather prominent nose.”

But Hoodie and his family also up-end convenient tropes. Hoodie’s a basketball player. His older sister, Zippy, wants to be an engineer, with moxie enough to persuade their father to get WiFi in the house. One of his younger sisters has a habit of lobbing projectiles—empty Amazon boxes, staplers, balls—from the family’s roof. Their mother, an educator, emerges from her home office barely in time for Shabbes.

Holy attention

If God is in the details, then Blum’s narrative is suffused with holy attention: the family’s two panini presses (one for meat-containing sandwiches, one for dairy); Hoodie’s penchant for kosher Starburst (the British-made candy passes muster; the American-made version does not); the ancient rabbi whose barely-understandable lecture in Hebrew somehow makes Hoodie feel seen.

Through Hoodie’s eyes, Blum pokes at the internal contradictions governing Orthodox daily life—for instance, without an eruv (a literal and metaphoric string wrapped around the town, extending the private home into the public realm and permitting activities that would normally be forbidden on Shabbes), Hoodie’s parents cannot carry their younger daughters or push a stroller to the synagogue after sunset on Friday.

It’s Hoodie who observes, translates, and—increasingly, as the novel unfolds—questions the precepts of this world, one he cherishes even as he finds its limits confounding and divisive.

Exile and embrace

When he persists in seeing Anna-Marie, his family and community respond with “cherem”—essentially, an internal exile during which Jewish neighbors avoid him, his best friend shuns him, and his father confiscates his flip-phone, Hoodie’s only means of communication with Anna-Marie.

While exploring questions of belonging and identity, hatred and courage, the story ramps to a climax that is tragically, painfully, real-world resonant. Hoodie breaks and heals, shames his family and is eventually re-embraced by them, experiences brief, worldwide renown and close-to-home, intimate grief.

He emerges changed: no less sarcastic than he was at the start, and without easy answers about how to square his Orthodox upbringing with the wider world, but with a deeper understanding of what is at stake—the gravity, potential, and love that ride on his choices.

What, When, Where

The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen. By Isaac Blum. New York: Philomel Books/Penguin Random House, September 13, 2022. 218 pages, hardcover; $18.99. Get it on bookshop.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman