Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Tales of epidemics past

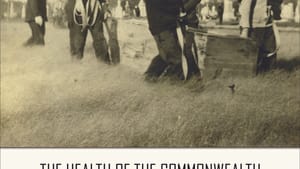

‘The Health of the Commonwealth’ by James E. Higgins

Though James Higgins’s narrative ends slightly before the arrival of Covid-19, the novel cornoavirus is an implied presence throughout Health of the Commonwealth: A Brief History of Medicine, Public Health, and Disease in Pennsylvania. The succinct yet comprehensive text traces the evolution of medicine and medical care, along with how society responds when overtaken by diseases it doesn’t understand. From yellow fever to Legionnaires disease to AIDS to Ebola, Covid is following a familiar script, although with better science.

Politics, industry, and medicine

“The history of medicine in Pennsylvania is no less vital to understanding the state’s past than its political or industrial history,” writes Higgins, a lecturer at Rider University. Moreover, those three threads have interacted since the colonial era to influence quality and availability of care.

Dividing the past into chronological, themed periods, the text, part of the Pennsylvania Historical Association series on state history, introduces people and topics worthy of more exploration. For example, the physicians who revolutionized battlefield care in the Civil War, one of whom was Samuel Gross (later immortalized on canvas by Thomas Eakins), who wrote an indispensible pocket surgical manual. Or the laboratory rats that the Wistar Institute bred in 1906, which some say are related to half of all modern lab rats.

The evolution of care

The book contrasts allopathic medicine (scientifically tested drugs, surgery, and other treatments administered by licensed, regulated practitioners) with the practices that predated it, which ranged from life-saving to quackery.

The Indigenous Lenni Lenape people of the region “cared for wounds and extracted foreign bodies, including musket balls, with a skill not matched by the most proficient colonial surgeons,” Higgins writes. “Treatments for skin problems, including burns and boils, were effective, and success was claimed with the bite of the copperhead and rattlesnake.” Native Americans stabilized fractures and closed wounds, prevented infection and reduced fever, but were defenseless against unfamiliar microbes that arrived with Eurasians and Africans and devastated Indigenous communities.

Eighteenth-century German immigrants combined Christian-based practices, Indigenous traditions, and botanicals in “powwowing.” According to Higgins, the practice “utilized sacred symbols such as crosses, stones, and other items thought to [heal or] draw out curses … The healing process demanded that both practitioner and patient believe in the power of powwow and Christ.”

Homeopathy, the "like defeats like" approach developed by German physician Samuel Hahnemann in the early 19th century, claimed that diseases could be overcome by ingesting small doses of substances that induced similar symptoms. Though unscientific, Higgins says, the practice was popular.

Patients had confidence in folk practices and, even if they didn’t actually cure disease, many of these practices inflicted less harm than the bleeding and purging that dominated treatments by early doctors. But as scientific understanding advanced, licensed medical practitioners abandoned ineffective, dangerous treatments. Beginning in the 19th century, physicians formed associations to enhance education and professional standards, and unscientific approaches lost credibility.

When public health came first

Today, absent a crisis like the current pandemic, public health often operates at the edge of popular awareness as it serves those without health insurance and enforces sanitary standards in the public realm.

Eighteenth-century public health, however, was quite visible as the only line of defense against repeated outbreaks fueled by crowded, filthy streets, contaminated water, disease-bearing pests, and unknown maladies arriving on each ship.

Public-health leaders applied available techniques, not all of them successful. Quarantining ill travelers helped; burning noxious smudge pots to “cleanse” disease-ridden air did not. Nevertheless, Higgins writes, “public health and public medicine reduced morbidity and mortality in the state long before effective treatments were developed for most diseases.”

Cities and large towns formed health boards, but rural areas lacked oversight until a statewide board was created, a measure delayed by politicians and unscientific practitioners. The former feared committing tax dollars, and the latter saw a challenge to their livelihoods. Typhoid outbreaks in northeastern and western Pennsylvania finally decided the question. A state board was created in 1886, and in 1905 was replaced with a stronger state department of health.

Women in medicine

For much of the past three centuries, the most familiar care provider was a midwife. Experienced midwives handled much more than childbirth, Higgins explains, and likely were more skilled than the average country doctor. This made midwives a valuable resource for poor families, and a threat to physicians struggling to establish their profession.

Most medical schools, meanwhile, excluded women. One exception was the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, founded in 1850. Known for its educational rigor, it accepted students of any class or race. But for the most part, women determined to practice medicine were shunted into midwifery or nursing. Nursing programs and hospitals multiplied after the Civil War, and increasing ranks of nurses expanded care as they worked in physicians' offices, schools, the community, and public-health organizations. In the face of disease for which answers did not yet exist, nurses offered practical care that improved conditions for patients.

The more things change

The déjà-vu quality of Health of the Commonwealth goes beyond the current pandemic. The book recounts ostracism of immigrants, blamed for causing outbreaks. It demonstrates that care quality and access has always depended on status and location. It reveals resistance to inoculation—for smallpox, a precaution George Washington ordered for soldiers at Valley Forge. And it reports a 19th-century backlash to recording vital statistics, because patients felt it reduced them to numbers, diminishing their relationship with physicians. From age to age, medical science changes, but people don’t.

Image description: The cover of the book The Health of the Commonwealth, by James E. Higgins. It has an old sepia-toned photo of men wearing white facemasks while carrying a wooden coffin through a field.

Image description: A black-and-white photo from 1900 showing a group of ten young women nurses posed in two rows. They wear white pinafores and gauzy-looking frilled hats.

What, When, Where

The Health of the Commonwealth: A Brief History of Medicine, Public Health, and Disease in Pennsylvania. By James E. Higgins. Philadelphia: Temple University Press in partnership with The Pennsylvania Historical Association, October 20, 2020. 138 pages, softcover; $19.95. Find it at Temple University Press.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.