Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

A Philadelphia graphic novelist at the top of his game

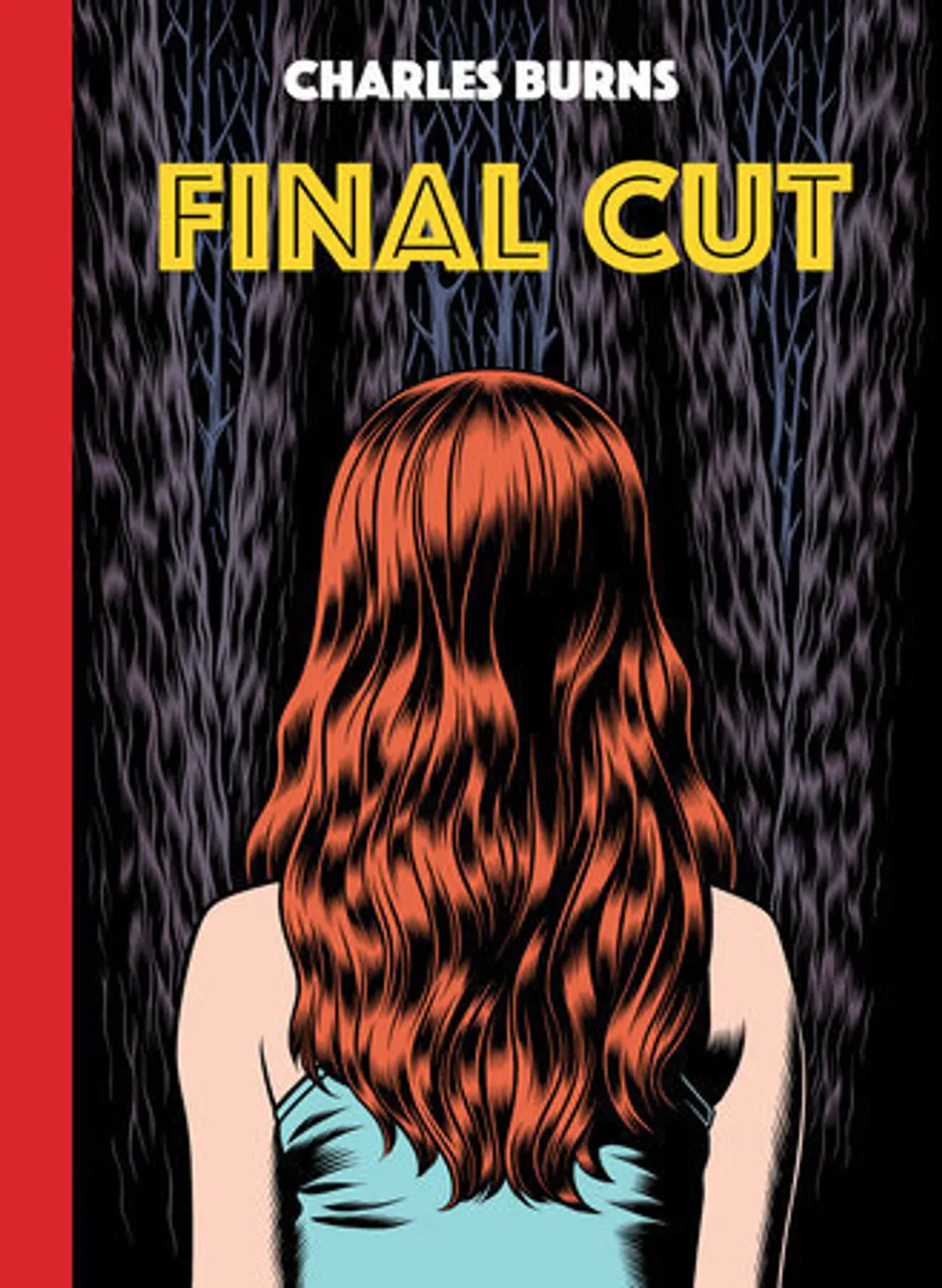

Final Cut, by Charles Burns

What is it that so compels us toward the images in our heads? Especially those that are deviant, disturbing, grotesque? This is the question at the heart of Final Cut, Charles Burns’s latest graphic novel. For Burns especially, it’s a ripe question. Few independent comics have achieved the kind of fervent cult following of Black Hole, the author’s now-seminal work about teens who contract bodily mutations through sexual contact.

In this new work, first published in France as three sequential issues, Burns returns to the thematic territory that Black Hole occupied—namely, teenage alienation made literal through Burns’s alien images—to tremendous effect. Final Cut is Burns at his best, a deeply ruminative work on the uncanny, executed with uncommon formal control. Like much of Burns’s work, it also carries a touch of the autobiographic. Brian, our protagonist, also an artist, is also drawn to the inexplicably strange.

Alien landscapes, human hearts

The year is 1971. Brian Milner is a soft-spoken teenager who loves to draw, making low-budget home movies with his childhood friend Jimmy. Their movies pay amateurish homage to the lurid cinema of their youth: The Flesh Eaters, Destroy All Monsters, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein. It’s at a screening/house party where Brian meets Laurie, an attractive girl with a glossy spill of red hair, and the soon-to-be star of Brian and Jimmy’s next film. She approaches Brian in the kitchen, where he’s drawing an alien self-portrait, a caricature of his warped reflection in a toaster. When she asks him what their new movie is about, he pauses for an eerie beat too long, then tells her: “The movie is about my head … It’s about all the fucked-up shit going on inside my head.”

It’s the kind of premise that Burns was born to write, a wistful portrait of early-70s Americana with dark psychological undercurrents roiling beneath. Burns, who is surely Philadelphia’s greatest comic artist, crafts an evocative simulacra of Brian’s mental landscape, intercutting the hazy images of day-to-day reality with stunningly precise phantasmagoric landscapes. A bulbous, pulsating alien becomes a recurrent symbol of Brian’s subconscious, floating like tumbleweeds over rocky plains. These dreamlike interludes, as surreal as they are, are woven continuously through the book’s reality. Whereas Burns’s past work would diverge into dreams in maximalist fashion—the edges of panels distorted in wavy lives, images crashing into each other like shards of broken glass—Final Cut offers no such digression. Its fantasies are presented as tangible objects, come to feel more real than reality.

Occasional images of film compound this blurring of art with real life. No scene in the book appears more painstakingly realized than a clip of black-and-white film: Timothy Bottoms and Cybill Shepherd in The Last Picture Show. Later, when Brian recalls the film to his friends, it’s his most outwardly emotional display in the book. Art, not life, becomes the conduit to these deeper emotional reservoirs.

Pursuing the questions

As Brian and Jimmy direct their film—a riff on Invasion of the Body Snatchers filmed at a cabin in the woods—the book further reveals itself as heir to a certain pulp tradition. Like so many comics of Burns’s childhood, it draws you in with the promise of strange sci-fi thrills but is powered by the engine of a romance. Amidst alien landscapes, it is the longing, the secret desire, the imagined kiss, that propel the characters forward. We never lose sight of Brian or Laurie—the latter especially becomes a far richer character than her introduction as a romantic muse would seem to suggest.

Throughout, Brian wrestles with his mental terrain, sleepwalking toward his mind’s eye in an almost alcoholic stupor. Are the images secret desire? Psychosexual longing? The yearning for stability in an unstable world? That’s all part of it, yes, but in the end, Burns is less interested in finding an answer than he is in the questions themselves, in their hazy, unknowable pursuit. Some half-octopus, half-brain floats just beyond our reach. Brian follows it, as do we, in Burns’s stark and sensual horizons.

What, When, Where

Final Cut. By Charles Burns. New York City: Pantheon Books, September 24, 2024. 224 pages, hardcover; $34. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Kiran Pandey

Kiran Pandey