Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Putting the collection in context

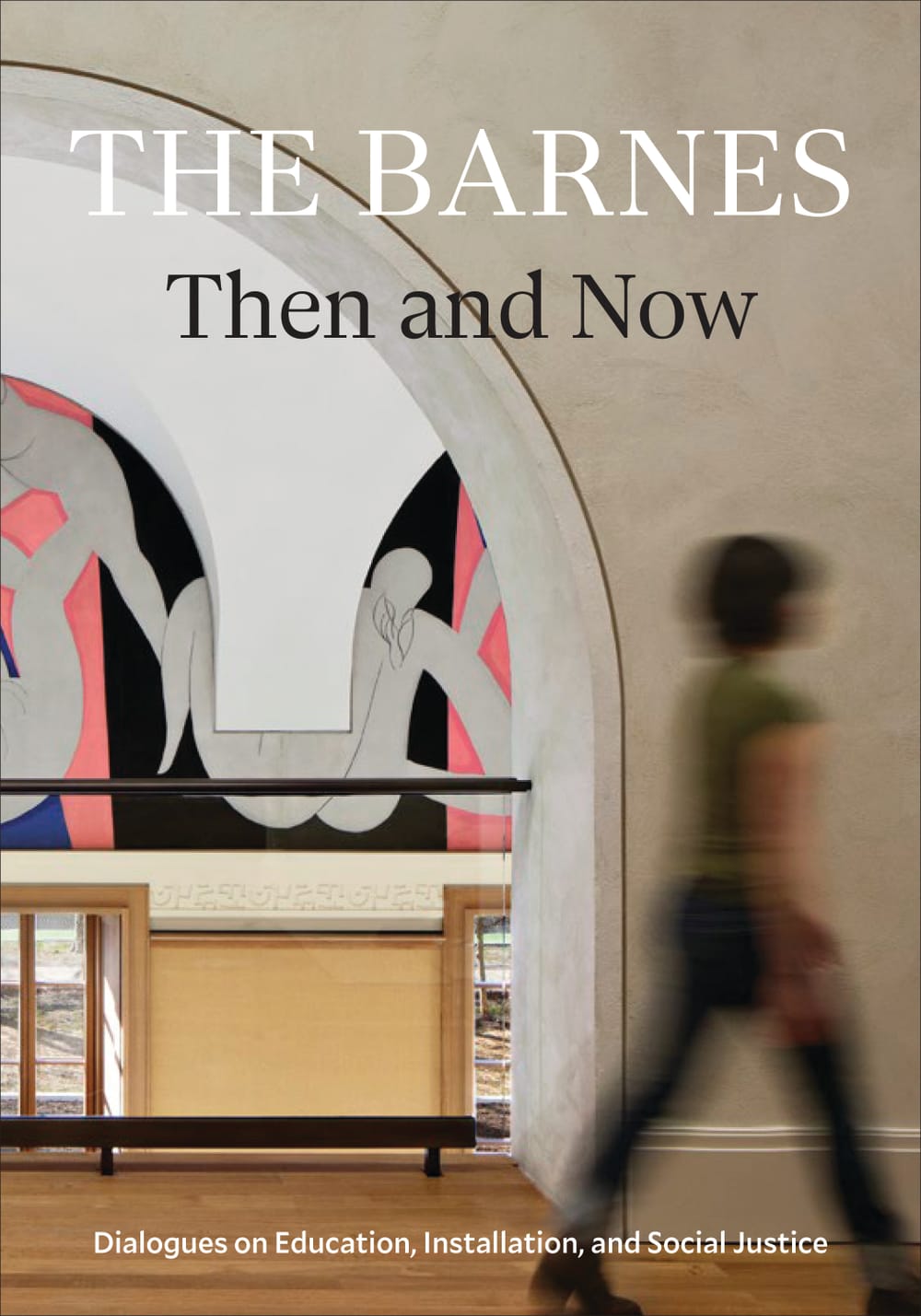

The Barnes Then and Now: Dialogues on Education, Installation, and Social Justice, edited by Martha Lucy

Now in its second century, the Barnes Foundation is a bit different from its neighbors on Benjamin Franklin Parkway. First, it isn’t a museum but an educational foundation, a distinction which has, on occasion, led to controversy. Its founder? Also controversial, due to his distinctly untraditional views on how art should be interpreted and shown. Was Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) an iconoclastic visionary or an eccentric egotist? In The Barnes Then and Now, a new book edited by Martha Lucy, inside and outside experts present nuanced assessments of the man and the foundation he created as it strives to honor its original mission and respond to changing expectations for the arts. This extensively illustrated volume includes essays and conversations on themes of education, installation, and social justice.

An anti-elitist founder

Its founder’s legacy continues to influence the Barnes Foundation in ways that are beneficial and challenging. He came from Philadelphia’s working class and made a fortune developing and marketing the antimicrobial drug Argyrol. By the time he was 30, Barnes was studying the arts in depth and collecting work by European modernists who had not yet gained acclaim, such as Pablo Picasso and Vincent Van Gogh. Initially, he hung paintings in his West Philadelphia factory to be viewed by mostly Black employees.

Barnes detested what he perceived as elitism in the art world, an attitude that made for capricious admission policies when the collection settled in Merion, Pennsylvania—art elites were often refused and public access was not granted until 1961. Barnes wanted ordinary people to experience the works, a view that grew from his admiration of the philosophy of John Dewey.

Progressive views, with flaws

Alison Boyd, who recently joined the foundation as director of research and interpretation, describes Barnes's thinking and the classes he offered for workers from 1908 to 1929. Though his aims were egalitarian, Boyd observes that Barnes made race- and class-based assumptions about Black students: for example, that they were better able to appreciate color, form, and rhythm than white students.

Tatiana Flores of the University of Virginia and Rebecca Uchill of the University of Maryland note limitations in Barnes’s opinions of African work. Notably, he was one of the first to collect and present it as art rather than ethnographic artifacts. Barnes thought European artists could learn from and be reenergized by African art but did not believe the reverse to be true. Also, though Barnes identified what he collected as “primitive,” his African masks and sculptures were produced contemporaneously with other pieces in the collection.

By 1925, when the first students entered the foundation’s Merion building, designed by Paul Cret, Boyd writes that Barnes’s goal “was nothing less than the social and political transformation of the United States.”

At war with the academy and the art museum

Ultimately, Barnes did not transform the nation, but he did turn the art world on its head.

Applying scientific principles he knew well, Barnes taught his art students to observe, question, test, and conclude. William M. Perthes, Barnes director of adult education, explains: “Ultimately, Barnes concluded that he could learn more directly from paintings than from any text written about them, and the foundation was intended to provide that experience for its students.” For Barnes, understanding art required nothing more than the ability to discern light, line, space, and an artist’s intention: titles and other contextual information were not essential and were not posted.

“Barnes’s insistence on this put him at war with a powerful alliance—the academy and the art museum,” said Rika Burnham, former Frick Collection head of education, in conversation with Perthes. “The method was like a line in the sand: this is where we begin, and this is what matters.”

After Barnes’s sudden death, his administrative and artistic principles were maintained by Violette de Mazia (1896-1988), who served the Barnes Foundation for more than 60 years and is the individual most identified with the institution after Barnes himself. Bertha Adams, associate archivist, writes, “The Barnes Method was Violette de Mazia’s mission. And over the years, she taught nearly five thousand students how to look at life and art.”

Polarizing ensembles

In 2012, the controversial relocation to Philadelphia was further complicated by Barnes bylaws stipulating that the original physical arrangement remain unchanged. That stipulation led to the exact recreation of the Merion galleries in the city.

Though ensembles, as the art arrangements are called, were frozen in place at Barnes’s death, he’d often moved things around. “The most decisive change,” according to Dario Gamboni of the University of Geneva, “was the inclusion during the 1930s of functional objects traditionally categorized among the decorative arts, which gave to the Barnes Foundation display its distinctive and ‘eccentric’ appearance.” When andirons and cast-iron fittings joined the Cezannes, the art world lost its mind.

Gamboni, an art historian, counters criticism of the approach, noting that styles change and some of Barnes’s preferences, such as spare galleries and natural light, are now standard. “Hanging medieval works around a large Renoir picture means that he finds other common elements more important,” Gamboni said in 2022, “It was also about demonstrating that modern works were at the level of older works.”

Even so, viewing the ensembles may not be easy due to crowding and odd positioning. And though Barnes championed African art, the original collection contains little by women and artists of color and depicts subjects who are mostly white. Lucy, Barnes deputy director for research, interpretation, and education, said in 2022 the issue is acknowledged with visitors: “We have a lot of students, young learners of color … and they’re not seeing themselves represented … so we talk explicitly about that problem.”

Context, after all

Achieving social justice through art education was Barnes’s imperative, and the foundation continues that mission, addressing evolving conceptions of what social justice actually means. To augment the original collection, changing exhibitions feature underrepresented artists and subjects. Technology, a digital application, offers visitors as much information as they wish so that, as Thom Collins, Barnes executive director and president explained, “Barnesian visual analysis is buttressed by sociohistorical context.”

New audiences are cultivated through outreach in Philadelphia schools, libraries, and recreation centers. Barnes pursued educational alliances throughout his life and the longest such relationship, an ongoing collaboration with Lincoln University, is profiled by Barbara Anne Beaucar, former Barnes archivist and historian, who spent years organizing Barnes’s voluminous correspondence with Horace Mann Bond, Lincoln’s first Black president.

The Barnes Then and Now is a thorough exploration of an institution many know only through dated headlines and hearsay. Ironically, it provides the very thing Barnes so readily dismissed when interpreting art: context.

What, When, Where

The Barnes Then and Now: Dialogues on Education, Installation and Social Justice. Edited by Martha Lucy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2023. 304 pages, softcover; $60. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.