Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The OGs of their genres

The Barnes Foundation presents Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes

This summer, the Barnes offers a rare and historic opportunity to see paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Henri Matisse in conversation with each other. Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes pulls these works out of their usual places in the collection’s permanent galleries, and I recommend taking them in.

Full disclosure: I’m not a Renoir fan, and I’m not alone (a @renoir_sucks_at_painting Instagram account has more than 18K followers). Important art critics such as Roberta Smith and the late great Peter Schjeldahl (and others) have skewered Renoir’s legacy of flaccid nudes. He is quoted as once telling a journalist that he painted with his prick. But a few of the Renoirs chosen by curator Cindy Kang and assistant curator Corrinne Chong for this exhibition are some of his best efforts.

Labor and leisure

Renoir (1841-1919) and Matisse (1869-1954) are the OGs of their respective genres: Impressionism (circa 1870s) and Fauvism (circa 1905). Matisse befriended the elder Renoir as a mentor in 1917, two years before he died. Both depicted bodies in spaces and achieved wealth and fame in their lifetime. Dr. Albert Barnes was dazzled by their works and collected them in abundance.

For this show, the Barnes reception room holds Renoir’s compelling Grape Gatherers (1888-89) where two women recline in a field on break from their labors. Although rendered using a vibrant prismatic palette with feathery brushstrokes, the viewer senses the workers’ physical and psychological fatigue. Since Impressionism typically concerned itself with scenes of leisure, I was struck by the Realist subject of poor workers. Nearby is Matisse’s Young Woman Before an Aquarium (1921-22), in which a brunette leans over a table gazing dreamily at her fishbowl. The two paintings are a cunning juxtaposition of class and leisure. It’s this kind of dialogue between artworks that thrill; it places images from long ago into a current context, connecting me to the past in a meaningful way.

Four more galleries to explore

The remainder of the paintings are arranged over four galleries by way of artist and period. The first highlights Renoir’s late work of landscapes, still life, and figures. A trip to Italy inspired classical awe and for the rest of his life, he aimed to move beyond the spontaneity of Impressionism. The second section displays Fauve works by Matisse that were so radical that critics called them “wild beasts.” His expressive lexicon of color exudes energy and daring such as in the outsized The Joy of Life, which shocked Paris audiences in 1906.

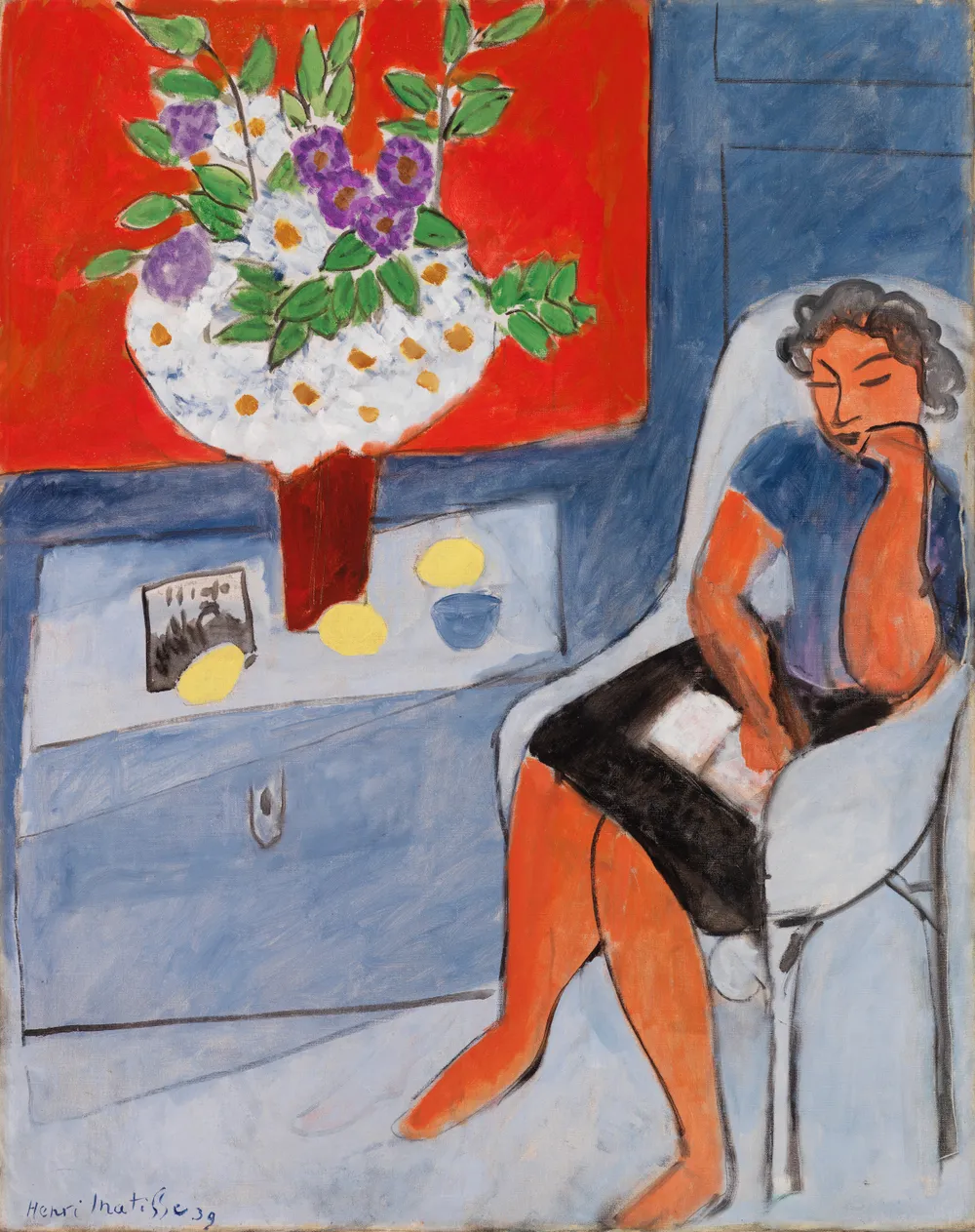

The third section displays large-scale paintings by both artists situated across from each other. Matisse’s Three Sisters (1917) triptych was a studied response to admiring earlier Renoirs. The arrangement of the paintings in the room encourages the viewer to spend time comparing. The final gallery is all-Matisse paintings of bourgeoise women in interior spaces referencing Renaissance nudes and Orientalism. The theme of leisure unifies these paintings in which Matisse creates a world of inactivity and pleasure. The exception is The Music Lesson (1917), where he renders a cheerful familial milieu while playing with real and imagined space.

The need to connect past and present

The Barnes promotional publications claim this exhibition is an expansion of the foundation’s educational program, with an emphasis on art historical contexts. Yet wall notes emphasize mostly biographical particulars for Renoir and Matisse. These underwhelming didactics skimp on political, cultural, and economic contexts. While the artists’ relationship certainly is interesting and relevant, I found myself with questions.

One display mentions how Matisse’s odalisques in the last gallery reference a “colonial fantasy of exotic non-Western sexuality.” This is a great example of the context we need, and I wish there was more of it, like reflections on the male gaze, objectified female bodies, representation, and class. Could the curators have addressed the absence of people of color in the work? Or how France at the time was struggling with post-Industrial Revolution social hierarchies, new environmental pollution, and rampant capitalism? Both artists seem to have ignored World War I, although two of Renoir’s sons were wounded on the front lines. Did their wealth make it easier to create a bubble?

Museum viewers are keen to understand art and history, not simply take in masterpieces. One hundred years ago, we were facing the same challenges: war, injustice, sexism, climate change, and financial instability. Art history and old art can generate new dialogues. Exhibitions are compellingly relevant when curators draw connections between the past and the present.

At top: Henri Matisse’s Figure with Bouquet, August 1939, Oil on canvas. The Barnes Foundation, BF980. © 2024 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

What, When, Where

Matisse & Renoir: New Encounters at the Barnes. Through September 8, 2024, at the Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. (215) 278-7000 or barnesfoundation.org.

Accessibility

The Barnes is accessible to standard-size wheelchairs and has designated parking for visitors with disabilities. Assistive listening devices are available and trained service animals are welcome; it offers complimentary admission for paid personal care assistants and ACCESS/EBT cardholders, including those receiving Medical Assistance only. More accessibility info is on the museum’s visitors page.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

K.A. McFadden

K.A. McFadden