Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Defying bias

American Philosophical Society presents Pursuit & Persistence: 300 Years of Women in Science

Maria Mitchell’s father bought her a telescope aimed toward the stars. Émilie du Châtelet’s father made sure she received a comprehensive education. Publishing was in Maria Sibylla Merian’s blood: with the craft, she and her daughters revealed the natural world. In Pursuit & Persistence: 300 Years of Women in Science, the American Philosophical Society (APS) introduces scientists whose first task was to defy societal biases.

The stargazing Mitchell (1818-1889) is considered America’s first professional female astronomer. She was the first to report sighting a particular comet that became known as “Miss Mitchell’s comet,” and her discovery is celebrated in a contemporary sculpture positioned near her story. The sculpture is one of several works on view by artist and lecturer Rebecca Kamen, who probes the connection between art and science, a connection instrumental to women who aspired to study science in the 17th and 18th centuries when art was deemed an “acceptable” vocation for aristocratic girls, while science was not.

Visionary views

Insects, particularly caterpillars, were fascinating to Merian (1647-1717), a German botanical artist who recorded them transforming into moths and butterflies. Her large-format book, The transformation of the insects of Suriname (1705), is full of delightful and accurate engravings of observations she made over two years of exploration. Merian’s travel through the South American Republic, then a Dutch colony, was guided by enslaved and Indigenous people.

One engraving depicts a pineapple as a laboratory of metamorphosis, pulsing with life: caterpillars crawl, pupae crack open, butterflies hover. Little wonder Merian’s drawings were purchased by Russian Tsar Peter the Great and Sir Hans Sloane, founder of the British Museum, which credits Merian with the development of entomology and zoology as independent disciplines.

Royal connections

Du Châtelet’s (1706-1748) father, a member of the court of Louis XIV, ensured that she learned six languages, mathematics, and science. She wrote Foundations of Physics (1740), a text that advocated a logical scientific inquiry.

Linguistic ability enabled du Châtelet to translate learned works, and she also corresponded with intellectual elites, such as officials at France’s Royal Academy of Science, which women were not permitted to join. One such letter, dated 1741, is on view here.

Collaborating with the philosopher Voltaire, she translated and summarized Isaac Newton’s Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy but received scant credit. The 42-year-old du Châtelet then undertook a full translation independently while experiencing a pregnancy she believed she would not survive due to her age. Working furiously, she added a mathematics section and personal commentary. Du Châtelet completed the work and died a week after giving birth. Her translation was published 11 years later.

Emma Diruf Seiler’s (1821-1886) father, court physician to the king of Bavaria, exposed her to art, music, and science, and she applied them all in studying the human voice. Singing provided women opportunities to perform and teach, but vocal problems led Seiler to question how sound is produced and shaped by vocal folds, tongue, and lips. To observe the process, she inserted a simple laryngoscope, a rod tipped with a small mirror, down her own throat and trained herself to sing with the rod in place.

She later wrote, “There is not only an aesthetical side to the art of singing, but a physiological and a physical side also … without an exact knowledge … what is hurtful cannot be discerned and avoided, and no true culture of art, and consequently no true progress in singing, is possible.”

In 1866, financial troubles forced Seiler and her two children to settle in the United States. Her books, The Voice in Singing (1868) and The Voice in Speaking (1874), were both published in Philadelphia. Seiler’s son Carl followed his mother’s lead, becoming a throat specialist.

Delayed, not deterred

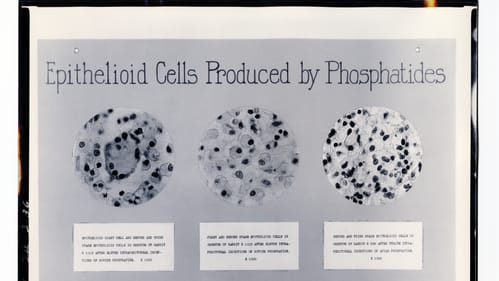

Immunologist Florence Rena Sabin (1871-1953) postponed entering Johns Hopkins Medical School to earn tuition by teaching. She became one of the first women to establish herself as a research scientist, was Hopkins’s first female faculty member, and authored An Atlas of the Medulla and the Midbrain, which became a standard anatomy text. In 1925, Sabin became head of the Rockefeller Institute’s cellular immunology section, where she led research into white blood cells’ role in fighting tuberculosis.

Sabin understood the importance of networking, joining groups of women scientists, compiling lists of colleagues, and advising anyone who sought her counsel. In 1931, she was the only scientist chosen among the nation’s leading women by readers of Good Housekeeping magazine (and an all-male selection panel). The group included social worker Jane Addams, author Willa Cather, and disability advocate and lecturer Helen Keller.

When Barbara McClintock (1902-1992) began studying botany at Cornell University, women were not permitted to study genetics. So, she studied the cellular characteristics of corn. At the University of Missouri, concluding she wouldn’t be granted tenure, she left. McClintock ultimately found an intellectual home at the Carnegie Institute in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, where she studied plant genetics for the rest of her life.

According to a National Institutes of Health profile, McClintock did “groundbreaking” research on the movement of genes in corn plant chromosomes, developing theories about how genetic information is suppressed or expressed. But “after encountering some skepticism about her research and its implications, she refrained from publishing her data in professional journals and only shared her research with a small circle of loyal colleagues.”

McClintock’s research was published in 1981. On view at APS are brown bags she used to cover corn tassels to control fertilization, inscribed with her penciled field notes.

Opening doors for new generations

Two recent pioneers have connections to Fox Chase Cancer Center: biochemist Mildred Cohn (1913-2009) became a senior scientist at Fox Chase following her 1982 retirement from the University of Pennsylvania, and developmental geneticist Bea Mintz (1921-2022) spent 60 years at the center investigating how cancer forms at the cellular level.

Women pursuing science still face barriers that have nothing to do with their capacity to learn, practice, or advance scientific knowledge, but those barriers are now less daunting thanks to the scientists on display at APS. They worked within and around existing systems, earned respect for their achievements, and opened the door a little wider with each generation.

Editor’s note: BSR associate editor Kyle V. Hiller is on staff at APS as the visitor services lead.

What, When, Where

Pursuit & Persistence: 300 Years of Women in Science. Through December 30, 2023, at the American Philosophical Society Library & Museum, 104 S 5th Street, Philadelphia. (215) 440-3440 or amphilsoc.org.

Accessibility

The APS Museum is on the second floor of Philosophical Hall, accessible by a flight of stairs. A wheelchair lift and elevator are available, and staff can help with their use. Visitors need only inquire at the entrance. Accessibility questions can be directed to (215) 440-3440 or [email protected].

Note that restrooms are not available on site.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.