Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

In plein sight

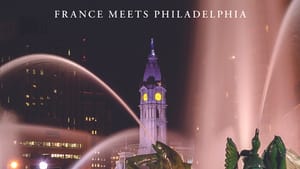

‘Salut! France Meets Philadelphia’ by Lynn Miller and Therese Dolan

Philadelphia has more in common with France than most of us realize. Salut! France Meets Philadelphia documents connections so extensive, so fundamental, that the book, by political scientist Lynn Miller and art historian Therese Dolan, reads like a history of the city told through French eyes.

Revolutionary precepts

French Enlightenment philosophers provided the theoretical underpinning for American independence. Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and Condorcet were read extensively by the founding generation, who used the rationale of equality and natural rights to argue for American independence. Members of the Enlightenment still living when the colonies separated from Britain viewed it as the fulfillment of theoretical aspirations.

The commonwealth's founder, William Penn, as well as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, spent time in France. Penn’s Quaker beliefs were informed by French humanism, while Franklin and Jefferson, who represented the emerging nation abroad, absorbed not only France’s intellectual outlook but its culture. The French adored Franklin, who conducted a nine-year charm offensive while negotiating critical military and trade assistance from 1776 to 1785.

Jefferson so loved France that he was reluctant to leave in 1789, after five years as United States minister. He shipped home crates of art, furniture, and books, including documents on political theory addressed to James Madison that would resonate through the US Constitution.

Culture and commerce

Within a decade of aiding the American Revolution, France initiated a revolt of its own. That uprising and another in the French colony Saint-Domingue caused so many to immigrate here that by 1795, one in 10 Philadelphians was said to be French. Principally aristocrats, the new arrivals influenced society and business, a pattern that continues: Miller and Dolan write that French influence in Philadelphia is most evident in high, rather than mass, culture.

The du Ponts illustrate the point. Pierre S. du Pont de Nemours arrived in 1800 and assisted in one of the most significant transactions in American history, the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. The agreement doubled the United States land mass overnight and fueled westward expansion. His son Eleuthère Irénée established a business manufacturing gunpowder on the Brandywine Creek that evolved into a chemical dynasty. Successive generations of du Ponts have influenced not only business but politics, art, and philanthropy.

Art lessons

The book’s 169 color illustrations, amplified by detailed interpretation, demonstrate that Philadelphia’s most obvious French ties are artistic: Philadelphia Museum of Art is home to the largest collection of French art outside France; the Barnes Foundation holds more works by Renoir and Cezanne than the nation of their birth; and Philadelphia’s Rodin Museum houses the largest collection of the artist’s sculptures outside France.

Artistic bonds extend beyond works on view to the formation of American artists, drawn to France for creative freedom and education. In the 18th century, Americans went abroad to bask in legendary museums, seek instruction from masters, and test themselves in government-sponsored salons. Among the first was Philadelphian Rembrandt Peale, who’d studied with his father, portraitist and Philadelphia Museum founder Charles Willson Peale, as well as studying in London, but felt his development depended on France.

To artists of marginalized groups, France offered acceptance not in evidence at home. In 1865, though women were not permitted to enroll in France’s premier institution, the École des Beaux-Arts, Mary Cassatt arranged private tutoring and sketched in the Louvre. The Philadelphian would spend her entire celebrated career in France. Similarly, African American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner found Paris more conducive to his artistic growth.

PAFA and Paris

Cassatt and Turner are two of several artists who sought training in France after studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA).

The most notable is Thomas Eakins, who would advance American art by representing workaday people and pursuits on canvas, including surgeons (The Gross Clinic, 1875) and athletes (Max Schmitt in a Single Scull, 1871). Eakins was an early adopter of photography to make preparatory studies, endorsed sketching from life, and as a PAFA faculty member, shocked his superiors and the public by employing nude models, a practice that eventually forced his resignation.

PAFA artists returned from France with expansive new ways of representing the world, including urban realism and impressionism, which developed a local variant, Pennsylvania impressionism, exemplified by Edward Redfield, William Schofield, and Daniel Garber.

Our Champs-Elysées

It isn’t necessary to enter a gallery to encounter Philadelphia’s French inheritance—just walk around. Many quintessential Philadelphia landmarks, most prominently the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, are the work of French architects Paul Cret and Jacques Gréber.

Cret, explain Dolan and Miller, “took his cue from the great diagonal slash of the Champs-Élysées and, like that boulevard, ended his Philadelphia avenue in an open space similar to its counterpart’s terminus at the Place de la Concorde.” In 1916, Gréber modified Cret’s 1907 plan, extending the boulevard beyond Logan Circle toward Fairmount Park. Gradually, elegant neoclassical buildings arose along the thoroughfare, including the Rodin Museum, on which Cret and Gréber collaborated in 1929.

Cret’s hand is visible across Philadelphia, in the design of Rittenhouse Square, the Benjamin Franklin and Henry Avenue bridges, and the original Barnes Foundation building in Lower Merion.

Below William Penn

Philadelphia is also punctuated by the art of a family of French-inspired artists, all named Alexander Calder. Alexander Milne Calder designed the iconic statue of William Penn atop City Hall, which itself is a prime example of French Renaissance architecture. Milne Calder’s son Alexander Stirling Calder produced the Swann Fountain at Logan Circle and the nearby Shakespeare Memorial. Stirling Calder’s son Alexander (Sandy) is known for the monumental mobiles that grace a number of prominent public spaces, including the great stair hall of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

From its founding to the present, Philadelphia has been shaped quietly by French visionaries. Though its French heritage may not be Philadelphia’s most obvious characteristic, it’s there to be discovered, subtly marking America’s first city as uniquely European.

The authors will discuss Salut! in a free virtual event on Wednesday, December 9, at 6pm at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

Image description: The cover of the book Salut!. It’s a nighttime photo of Philadelphia City Hall, its tower with clock faces illuminated in yellow. In the foreground is the Swann Fountain sculpture by Alexander Stirling Calder, which has giant naked human figures reclining with fishes or birds on their backs. The view is crossed by arcs of water from the fountain.

Image description: An 1871 painting by Thomas Eakins titled Max Schmitt in a Single Scull. It shows a rower in his boat with his back to the viewer, but turning his face over his right shoulder to look. The river he’s on is very calm. The glassy water reflects the blue sky, the boat, the brown banks and trees, and bridges in the distance.

What, When, Where

Salut! France Meets Philadelphia. By Lynn Miller and Therese Dolan. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, November 20, 2020. 416 pages, hardcover; $40 at Temple University Press.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.