Missing Kennedy’s energy

Round House Theatre and McCarter present Adrienne Kennedy’s ‘Etta and Ella’

After a month’s delay due to COVID-19 restrictions, this month Adrienne Kennedy’s Etta and Ella on the Upper West Side had its world premiere thanks to McCarter Theatre Center and Round House Theatre’s streaming festival of Kennedy works, which launched in November.

An unconventional voice

Kennedy’s work was first popularized during the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s, and her best-known work, Funnyhouse of a Negro, won an Obie Award in 1964. Despite an induction to the Theater Hall of Fame in 2018, her oeuvre, though prolific, has remained largely excluded from the canon and untouched by theater companies. Being a Black woman with an unconventional voice has never endeared one to traditionally white institutions like the theater.

With an experimental style that has been called (and perhaps dismissed as) surrealist and absurdist, Kennedy’s work often touches on very real themes of race, mental health, family dysfunction, and social inequity. The recent renewed interest in her work during a resurgence of racial tensions and reckonings in this country allows for fresh perspectives on her evergreen narratives.

Etta and Ella

Etta and Ella Harrison are two sisters in a codependent and competitive relationship, professionally and personally. Each is respectively brilliant and accomplished, but their lives, memories, and work become so enmeshed that mania and, eventually, murder ensue. Here, a sibling rivalry of such epic proportions is not larger-than-life as one might expect, but nuanced and niche in its neuroses. Adapted for the stage from a longer narrative piece, Etta and Ella is a complex tapestry of layered timelines, narrative voices, and literary styles (including poetry, prose, and monologue) tightly woven into just a few pages.

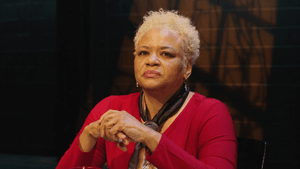

In stark contrast to the intricate writing, this production is very sparse. Caroline Clay stars in a one-woman show, appearing as a vision in a red dress and scarf. Her eyes are intense and expressive, and her golden fro frames her head like a halo. With the exception of her entrance and exit, she is seen only from her torso up while sitting at a desk outfitted with a red cup and an answering machine. Lights projected on the background allude to an ambiguous and blurry New York cityscape.

Kennedy’s expression

Though Clay is credited as playing the role of Ella Harrison, she is every character, and indistinguishably so. While I assume part of Kennedy’s intention with the original piece was to recreate the disorientation and delusion of madness, a stage adaptation might be expected to add some elements providing additional context, insight, access, or clarity. Instead, I found that director Timothy Douglas’s interpretation made the content harder to engage with and understand. Clay is at once eloquent, elegant, and as dynamic as she can be.

But she can only do so much solo and seated. The source material simply demands more than a static, single-framed shot can deliver. The production feels like a table reading or an audiobook recording rather than a fully realized performance, leaving a disconnect between the story and what viewers see. Some well-timed pauses, different angles, pictures, or projections might have helped add texture. Coronavirus constraints undoubtedly played a role in this. But while the pandemic era presents new limitations, it also offers opportunities for artistic experimentation and innovation. And something a little more energetic, edgy, or eclectic would have been more in line with and in service to Kennedy’s evocative expression.

Up to the challenge

With all the political theatrics playing out in our lives and on our screens already, theater as an evolving medium has its work cut out to find its lane in this new landscape and to discover fresh ways to entertain, engage, and enlighten us. Kennedy’s body of work is up to the challenge, and I am excited to see future iterations and interpretations of this piece. That new generations are being introduced to and engaging with Kennedy’s work is invaluable.

Image description: Actor Caroline Clay, a Black woman, sits with her elbows on a desk and her hands joined in front of her, looking at the camera with a wary expression. She’s wearing a long-sleeved bright red dress and brown scarf, and there’s a brick backdrop behind her.

What, When, Where

Etta and Ella on the Upper West Side. By Adrienne Kennedy, directed by Timothy Douglas. Available to stream from Round House Theatre and McCarter Theatre Center through February 28, 2021. Stream the show at mccarter.org.

Closed captioning is available.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Hanae Mason

Hanae Mason