Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The three hundred years’ war

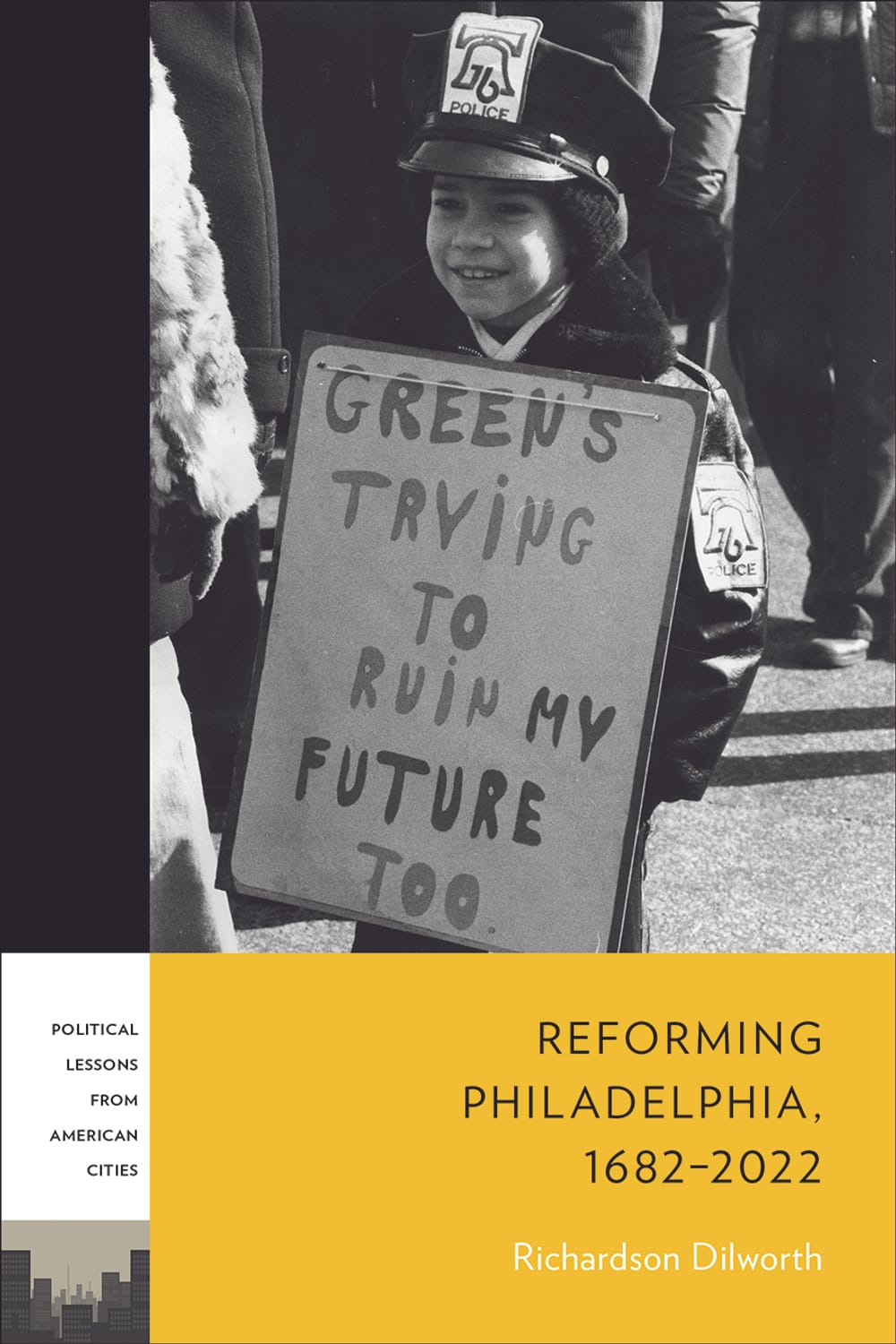

Reforming Philadelphia, 1682-2022, by Richardson Dilworth

“Reform” might not be the first word identified with Philadelphia politics, but author Richardson Dilworth contends that it has happened several times in city history and, potentially, is happening again. In Reforming Philadelphia, 1682-2022, the Drexel University professor defines what a reform cycle looks like and evaluates periods of city history in those terms.

At less than 100 pages, the book is packed with details of a three-century tug-of-war between power-wielding machine politicians and coalitions of reformers. Dilworth, who heads Drexel’s department of politics, is the grandson of Richardson Dilworth, mayor from 1956 to 1962, whose public service coincided with one of Philadelphia’s brightest civic eras.

What makes a reform cycle?

Dilworth defines reform cycles as periods in which government changes in response to evolving ideas about the city and its purpose. In addition to new ideas, reform cycles require four things: actors who challenge the prevailing power structure; elections in which reformers gain some control; implementation of new ideas; and acknowledgement by the public and the media that reform has taken place. By this model, Dilworth concludes that Philadelphia experienced periods of reform in 1905-1916, 1951-1962, and 1991-2000.

Reform can be driven by watershed events, as in 1854, when Philadelphia grew overnight from two square miles to 130, merging with its six surrounding boroughs and 13 townships. Dilworth writes that the 1854 consolidation made possible new coalitions that gave Republicans dominance in city politics for almost a century.

Not surprisingly, consolidation faced strong opposition, but became feasible as elites saw the benefit of combining. In 1846, regional leaders collaborated to establish the Pennsylvania Railroad linking Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, which circumvented a proposed B&O Railroad link between Pittsburgh and Baltimore, thereby protecting a valuable trade route.

New coalitions needed

Though 18th- and 19th-century reformers would not recognize the terms synergy and networking, they understood the concepts. According to Dilworth, reform cycles are “incubated in social networks fostered in … business associations, among intellectual communities at universities, in local media outlets, in liberal labor unions, and, more recently, in philanthropic foundations.”

Bankers, lawyers, merchants, physicians, and other elites met and socialized in private clubs and fraternal organizations. Farther down the social scale, concerned citizens congregated at work, in church, or through community groups. And when the impetus for reform crosses class lines, movements gain political influence.

This happened early in the 20th century, in the Progressive Era, when considerations of education, safety, health, and living conditions entered the public conversation, and people’s expectations of government began to change. Progressive professionals led reform groups and backed candidates willing to challenge entrenched interests. Blue-collar laborers increasingly gained leverage through unions and, when necessary, striking for improved wages and working conditions.

Dilworth notes that reform movements and political machines are similar in the way they form and operate. The machine acts to preserve its power, and reform groups work to gain influence. “The city had been organized … to serve the interests of a large coalition that only partially overlapped with the city’s business leaders,” Dilworth writes, “thus, those business leaders organized and led reform efforts against the perceived (and real) abuses of the machine … the categories … would define much of the dynamism in city politics throughout the twentieth century.”

Context is key

Reform cycles require more than just crusading leaders, however. The surrounding environment has to be ripe for reform. Dilworth contrasts the mayoral administrations of W. Wilson Goode (1984-1992) and Rudolph Blankenburg (1911-1916). Both had campaigned as business-friendly reformers, faced opposition, and are not considered effective mayors, but only Blankenburg is remembered as a reformer. Dilworth credits the disparity to Goode having led Philadelphia during the Reagan era, when the less-government-is-good-government idea prevailed. Blankenburg, however, took office as Philadelphia’s population and economy were on the rise. Additionally, Goode was Philadelphia’s first Black mayor, and his race, rather than reform reputation, takes precedence in public memory.

As a former district attorney and Democratic insider, Edward G. Rendell was hardly a reformer when elected in 1991, but Philadelphia faced multiple crises of massive debt, rising crime, and epidemics of AIDS and drugs. Jobs and residents were disappearing, leaving the city poorer, less able dig out of a deepening financial hole. “If Rendell was not interested in reform,” Dilworth writes, “he found himself mayor in a context that practically required it of him—in stark contrast to Goode, a reformer in the absence of the conditions necessary for reform.”

Complemented by a pro-business Democrat (Bill Clinton) in the White House and better federal funding, the Rendell administration (1992-2000) made city government more efficient, transformed deficits into surpluses, and attracted new investment and development into Center City that brought back employers, residents, and visitors.

Is it happening again?

Dilworth believes that Philadelphia’s contemporary landscape is similar to that of a century ago. Reform is on the rise, spearheaded by groups like Reclaim Philadelphia, Philadelphia 3.0, the Working Families Party, and the stalwart Committee of Seventy, which has been holding the powerful to account since 1904.

Hopeful signs include the passage of campaign-finance rules, advocated by then-City Council member Michael Nutter (mayor from 2007-2015), and new faces running for office, challenging assumptions about accepted practices in planning, land use, and “councilmanic prerogative.” Formerly third-rail issues, such as the soda tax, are being discussed and passed, and the conversation about city services is evolving to include things like universal pre-kindergarten. Dilworth even finds value in Trumpism, which he says galvanized reform in Philadelphia, leading in 2017 to upset wins by District Attorney Larry Krasner and former City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart, now a mayoral candidate.

The myth of Philadelphia

While Philadelphia may never be as perfect as reformers envision, nor as tightly controlled as organized politicians might want, the tension between those groups energizes and unifies the city around a myth of possibility, which Dilworth describes as “inherently corrupt, virtually always on the brink of some form of collapse, yet also perennially worthy of redemption. However illusory it may be, this myth of Philadelphia is the conceptual glue that has maintained a sense of political identity for more than three centuries.”

What, When, Where

Reforming Philadelphia, 1682-2022. By Richardson Dilworth. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2023. 130 pages, paperback; $19.95. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.