Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Making theatrical sense of Joyce

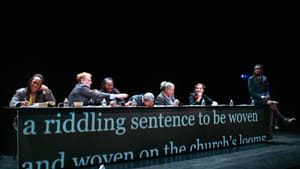

Philly Fringe 2024: Elevator Repair Service presents James Joyce’s Ulysses

Two years after the 100th anniversary of James Joyce’s Ulysses, New York-based theater company Elevator Repair Service takes its adaptation of the iconic Irish novel on the road, including a quick stop at this year’s Philly Fringe. The show drew me because I have struggled with Ulysses since my graduate days.

As a former academic attracted to race, gender, and dense 18th-19th-century novels, Joyce's monument to Modernism befuddled me. Joyce cared less about clear, linear narrative and more about innovative word construction. You read Ulysses less for the plot and more for the linguistic constructions. But Elevator Repair Service dares to adapt an abridged version.

Must-read, rarely finished?

Joyce's Ulysses is a novel every English major must read alongside Homer's The Odyssey and Samuel Richardson's Clarissa (unabridged), yet no one ever finishes. As I have 688 pages filled with marginalia that I barely remember writing, I wondered how anyone could make theatrical sense out of Joyce’s deliberate nonsense. I volunteered to review this play to see if a theatrical visualization would overcome my hatred of the text.

Was it successful? Partially. The deliberate academic reading style of the show’s first half reminded me of why I disliked Joyce, but I loved it when the second half leaned into a more visual production.

Facing a smug obsession

The first half was excruciating as it reminded me of my dislike of Joyce’s smug obsession with words over characters. A theatrical fast-forward effect smartly reflected how readers typically treat Joyce, where we read just a couple of pages before flipping to the next section. However, because Joyce focuses on sentences over sentience, the show became more like a catalog of events.

Without viewing Joyce’s erratic sentence construction, having actors just announce chapters or quickly enact truncated scenes felt more like Joyce abridged rather than the fresh re-envisioning of Ulysses I hoped for. It reminded me of the video installment of Ulysess I saw at the Museum of Literature Ireland, with concurrent videos playing of actors tonelessly reading Joyce, but without emotions or joy or the novel’s frenetic energy to bring it to life.

Theatrical changes

When the show’s second half leaned into visual theatricality, it gave a fresher spin to Joyce. While Ulysses has become the seminal Irish novel, many overlook Joyce’s usage of a Jewish lead in Leopold Bloom and his over-inclusion of antisemitic sentiments in almost every single chapter. Elevator Repair Service wisely cuts down those epithets. However, staging Bloom’s confrontation with the Citizen as an encounter with drunken buffoons rather than an episode of blatant antisemitic hatred, which forces Bloom to investigate his own identity politics, softened the bite too much. Likewise, the staging of the Nausicaa episode captured the sensuality of Bloom’s sexual awareness but softened the creepiness of a middle-aged man masturbating to a 17-year-old disabled girl.

However, as the second act progressed, with wild staging, including desks and light filling the space, Bloom and the character Stephen journeyed the areas together and brought the text to life.

My favorite moments weren’t the text but the theatrical flourishes. I loved it when the novel’s words literally overwhelmed the stage. I laughed at Bloom’s personified cat (Christopher-Rashee Stevenson) and actor Kate Benson air-flicking invisible snot. I enjoyed the show’s opening staged as students in a class, and its closing in a pseudo dissertation defense. Each actor had their moment, including Stephanie Weeks as the opening narrator, Scott Shepherd as Boylan\Buck, Maggie Hoffman as Molly Bloom, and Dee Beasnael's voice.

Most importantly, like my fellow BSR reviewer, I respected the decision not to truncate Molly’s voice. Considering female voices appear only twice in the novel, the decision to truncate all of Joyce’s writing except Molly’s closing monologue was extremely smart and added a modern spin to an old piece.

Is this for you?

If you are a hater of all things Joyce, no, this play is not for you. It will just activate old academic traumas. However, if you love Ulysses and quirky, weird plays (with the realization the first hour might be confusing), then give it a try if you get the chance (the show’s Fringe run ended on Saturday, September 7). To me, Ulysses always felt like the ultimate white male novel. However, in this case, a cast with racial and gender diversity changed that.

What, When, Where

Ulysses. Text by James Joyce with dramaturgy by Scott Shepherd, directed by John Collins. $49 ($15 for students and anyone under 25). September 5-7, 2024, at FringeArts, 140 N Columbus Boulevard, Philadelphia. (215) 413-1318 or phillyfringe.org.

Accessibility

FringeArts Theater is a wheelchair-accessible venue with gender-neutral restrooms. Hearing assisted headsets are available. Complete accessibility information is available on the FringeArts website. Ulysses contains periodic use of fog, bright lights, and loud noises.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

An Nichols

An Nichols