Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Democratizing American art

Penn’s Ross Gallery presents From Studio to Doorstep: Associated American Artists Prints, 1934-2000

That sketch hanging in your parents’ living room, the one you loved growing up—or hated? You might have Associated American Artists (AAA) to thank. For most of the 20th century, AAA enabled people of modest means to acquire art affordably and conveniently. Its legacy and works are recalled at Arthur Ross Gallery in From Studio to Doorstep: Associated American Artists Prints, 1934-2000.

For $5 in 1934—about $106 today—you could purchase a limited-edition print of new graphic art by someone like Grant Wood or Thomas Hart Benton. For each creation, AAA paid artists $200 ($300 if they were well known), and published no more than 250 copies.

According to the Smithsonian Institution, the company published more than 600 limited edition prints between 1934 and 1945. The company advertised in mainstream periodicals such as Time, Life, and Reader’s Digest, and sales were conducted by mail-order. In 1939, AAA opened a Fifth Avenue gallery in New York to display sculpture and paintings. In the 1950s, it expanded into home décor, including wallpaper, textiles, and ceramics.

A whole new way to market art

From Studio to Doorstep focuses on prints and lithographs from the University of Pennsylvania art collection, along with documents that accompanied purchases. There are also examples of AAA’s attention-grabbing advertisements, such as one from Life’s November 17, 1941, edition that trumpeted, “What! Only $5 for a SIGNED ORIGINAL by THOMAS BENTON the Great American Artist … Yes, INCREDIBLE but TRUE!”

Founder Reeves Lewenthal perceived opportunity in the depths of the Great Depression, when artists and many others truly were starving. Artists would be willing to create work for guaranteed income, he reasoned, and those fortunate enough to have incomes would be receptive to affordable, good-quality prints and lithographs. Lewenthal proceeded to commission work, build a catalog, and advertise widely.

He saw a market for art beyond wealthy, elite collectors. His advertising explained AAA’s philosophy to prospective customers: “To set up a worthwhile heritage and incentive for the younger American artists … to stimulate further interest in American art.” Readers were assured of exclusivity (“Editions strictly limited”), and were invited to send for a free catalog.

Ads were positioned alongside everyday products like toothpaste and coffee, notes Lynn Smith Dolby, Penn art collection manager and assistant curator. “The business model was completely novel, brokering a direct relationship between contemporary artists and consumers through mail-order sales and, for a time, through local department stores.” Positioned beside household commodities, art competed for disposable income.

A new home for artists

Benton (1889-1975) was among the first to sign. His lithograph Goin’ Home (1937) typifies the rural, sentimental themes of early AAA work. Two children drowse in the back of a horse-drawn cart, legs dangling off the back as their father drives along a narrow road in the moonlight. The label includes Benton’s recollection of creating the work: “From a drawing made – 1928 – in North Carolina – Smokey Mountain country. With a companion driving the car I followed these hill people until the drawing was finished.”

John Edward Costigan’s (1888-1972) similarly titled engraving Going Home (1940) could be a scene from The Grapes of Wrath: a family crosses desolate land on foot, accompanied by an exhausted horse. The father and horse walk in shadow, heads hanging. The mother and two children are bathed in light. She carries one child and gazes up, as if following a star. Her other child, a small girl, walks behind, seeding the ground from a bag she carries at her hip. Beams radiate around the family, glorifying them.

Initially, the artists were mostly white men producing representational works, but over time, contributors and artistic style diversified. Dolby credits the influence of Sylvan Cole, AAA director and president from 1958 to 1984: “Despite his admission of not being particularly risky when it came to contemporary art, Dorothy Dehner’s Mirage, Red & Black (1971) is an example of exceptional abstract work.” Interestingly, Dolby says, Cole turned down abstract expressionists Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol. Conversely, there are indications that Lewenthal once approached, and was rejected by, Jackson Pollock.

Art for everyone, by everyone

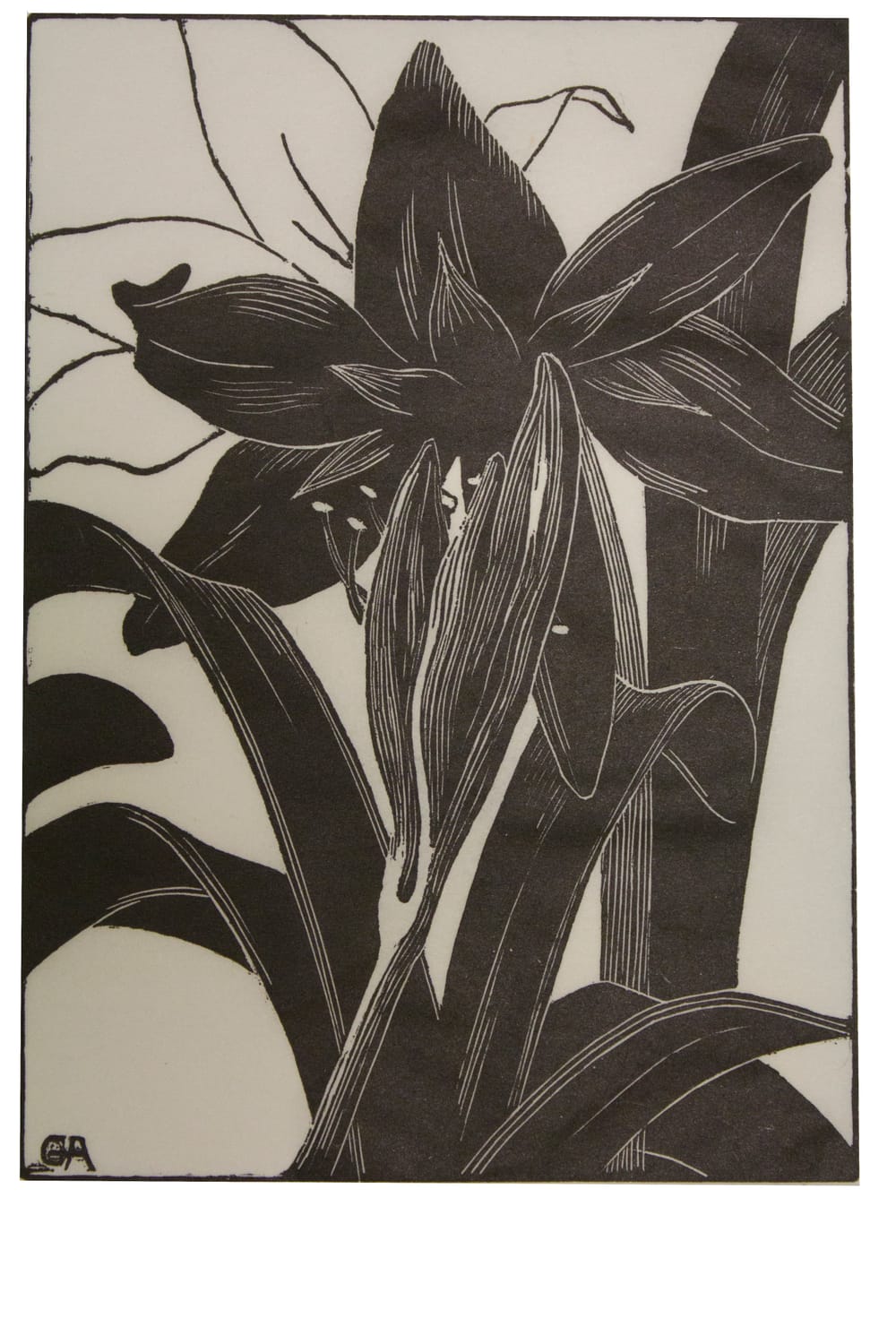

Women are well represented in the exhibit, including Grace Albee (1890-1985), whose Amaryllis (1978), an elegant woodblock print, greets visitors, and Norma Morgan (1928-2017), a Black painter and engraver known for depictions of the Scottish moors, whose Moorland Sanctuary (1972) is included. The exhibition’s latest work, The Big Snow (1984), was created by the youngest artist represented, printmaker Sarah Sears (b. 1953).

Mexican People (1946), portraits of workers grinding maize, laying brick, cutting down trees, and mixing clay for pottery, was created by many artists, most of them Mexican. The bucolic lithographs show native and Indigenous laborers producing goods Americans encountered in trade, but can also be read as populist statements: many of the contributors were active in the Mexican Muralist tradition championing workers, and some were members of the Mexican Communist party.

Irrespective of political agendas, the works are excellent. Grinding Maize by Leopoldo Méndez (1902-1969) depicts thatched cottages as big as mountains, overwhelming a courtyard where tiny people go about their chores, a woman kneeling at a grindstone, a man tilling soil, and a field hand toting sheaves on his shoulders.

From the other side of the globe, Korean painter Tchah-Sup Kim’s etching Window (1977) is simply sublime. Kim (b. 1942) shows a wood-frame window with a vine curling down one side. He doesn’t provide us a view through the opening, but instead directs eyes to the impossibly fine screen that spans it, the grain so microscopic that it looks like velvet. How did he create it? Whatever the print cost, whatever its provenance, this picture is priceless.

What, When, Where

From Studio to Doorstep: Associated American Artists Prints, 1934-2000. Through August 21, 2022, at Arthur Ross Gallery, University of Pennsylvania Fisher Fine Arts Building, 220 South 34th Street, Philadelphia. (215) 898-2083 or arthurrossgallery.org.

Face masks are optional inside the Fisher Fine Arts Building and Arthur Ross Gallery.

Accessibility

The accessible entrance to Arthur Ross Gallery and Fisher Fine Arts Library is through the Duhring Wing, on the building’s south side opposite Irvine Auditorium. To access the entrance, call (215) 898-2083 in advance, or (215) 898-1479 (guard’s desk) when on site.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.