Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Spiritual art … with a twist

PAFA presents Making Strange: Sacred Imagery and the Self

Jesus appears perturbed. In Albert Van den Berghen’s Ecce Homo (c. 1886-1889), on view in Making Strange: Sacred Imagery and the Self at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), Christ narrows his eyes, surveying those clamoring for his crucifixion. This is not the patient stoicism believers have come to expect.

Which is exactly the point. "Making strange," a term coined by Temple University art historian Marcia Hall, refers to artists’ expression of divergent views through the distortion of sacred images, thereby deepening viewers’ engagement, a movement that originated during the Counter-Reformation (1545-1648). Curated by Han McCoy of PAFA, the exhibition surveys the technique across time, cultures, and faith traditions, as embodied in work from PAFA’s collection and produced through its Brodsky Center for Papermaking and Printmaking.

Leave assumptions at the door

Visitors are meant to take their time, view closely, and see what’s actually shown, rather than what they expect. Helpful handouts offer guidance on elements to seek out and questions to ask.

Van den Berghen’s papier-mâché work is one of two pieces in this exhibition titled with the words attributed to Pontius Pilate as he presented Jesus, crowned with thorns, to the crowd: “Behold the man.”

Umberto Romano’s painting Ecce Homo (1947) shows Jesus, hands tied, leaning over another man on the ground, as though the two were walking in a line and the first man stumbled. Arms outstretched, the man reaches one hand toward Jesus while the other is flat on a piece of wood, palm up. Is he a thief being positioned on his cross? A guard leading prisoners to Calvary? The work is dark and the subjects twisted, consuming the whole canvas, which adds to the sense of misery and confinement. A bright spot on Jesus’s garment stands out, a small waterfall, flowing along his ribcage. Does it foreshadow the water and blood that will flow from his side on the cross? Nothing is clear.

What’s the meaning of this?

Another pair of entwined figures dominate Chitra Ganesh’s Delicate Line: (Corpse She Was Holding) (2009-2010), an abstract interpretation of sacred Hindu art. We see an amalgamation of body parts: lots of arms, a hand with 15 fingers, a nipple on a chin, and two animal heads, which stretch up and back, like sword swallowers. In Hindu iconography, multiple arms traditionally signify divinity. Is one of these a goddess and one a corpse, and if so, which is which? Would the image so perplex a viewer better versed in Hinduism?

In Ex Voto (2000), Rodríguez Calero combines Catholic and Egyptian symbols. The lithograph is a head-and-shoulders view of a young woman, her eyes closed demurely, wearing a blue wrap—visual signals indicating the Virgin Mary. Except this Mary wields symbols of pharaonic authority, the crook and flail, which she holds crossed over her chest, in the style of King Tut. Pharaohs were seen as intermediaries between people and the gods, and Catholicism confers a similar status on Jesus’s mother, presenting her as an intercessor for believers with her son. The Latin title, Ex Voto, which translates to “from the vow made,” refers to offerings made in gratitude to a saint or divinity. This raises the question: is the lithograph the artist’s offering, or merely a depiction of an offering being made? And, if the latter, by whom, and for what favor?

Still significant

Several pieces in Making Strange diverge from organized religion to explore secular humanism and personal spirituality, addressing societal, political, and ethical themes.

Nell Painter’s William Still Triptych (2022) masterfully communicates the transcendent significance of the Underground Railroad, by which people escaped enslavement. Philadelphia abolitionist William Still, a free Black man, provided funding and shelter for the effort, but his greatest contribution is the record he kept, at great risk, of escaping travelers, their names, and where they were headed. Still’s recordkeeping would enable many formerly enslaved families to reunite.

Consisting of jagged lines sweeping upward and converging in the upper right corner, the first panel could depict the blood vessels of a hand until you notice that each line is inscribed with handwritten echoes of Still’s jottings: “Sep 9 56 Arrived (4) Four Came at one Arrival as follows Geo. Solomon … May 25 56 Arrived Giles & Harriet Eglan both escaped.” In the second panel, the paths have become folds in a woman’s billowing skirt, converging at her head. She seems to be moving forward, looking back as she goes. In Painter’s last panel, the paths form a map of the Chesapeake Bay estuary, the lacy waters of which were traversed by Black people escaping along the railroad’s easternmost routes.

The sacred in the mundane

The works in Making Strange are organized into sub-themes, including Found Objects, where we find Willie Cole’s amazing print Quick as a Wink (2002), which transforms a household appliance into a contemplation.

Photographed from above, we see an iron, unrecognizable as itself. Instead, it’s a gleaming amphora or even an elongated tribal mask. Patient gazing reveals its true identity and with that, the realization of who sees an iron from this angle: the person doing the pressing. This leads to thoughts of meticulous mothers, invisible domestics, the heat of laundries and steaming clothes, and then, the other things to which hot irons have been applied: hair deemed inappropriate, and, most heinously, human skin.

Pause, inspect, reflect

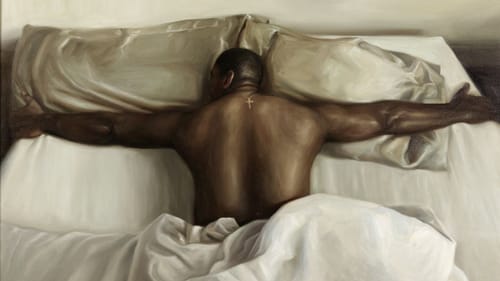

Though neither artist may have intended it, works by Yvonne Muinde and Philadelphia’s Anne Minich stand at the intersection of religious practice and art appreciation. In Muinde’s painting Blind Faith (2002), a Black man is spread-eagled and face down on a bed dressed with snowy linens. His position mirrors the small gold crucifix hanging on a chain between his shoulder blades. He grips either side of the mattress tightly.

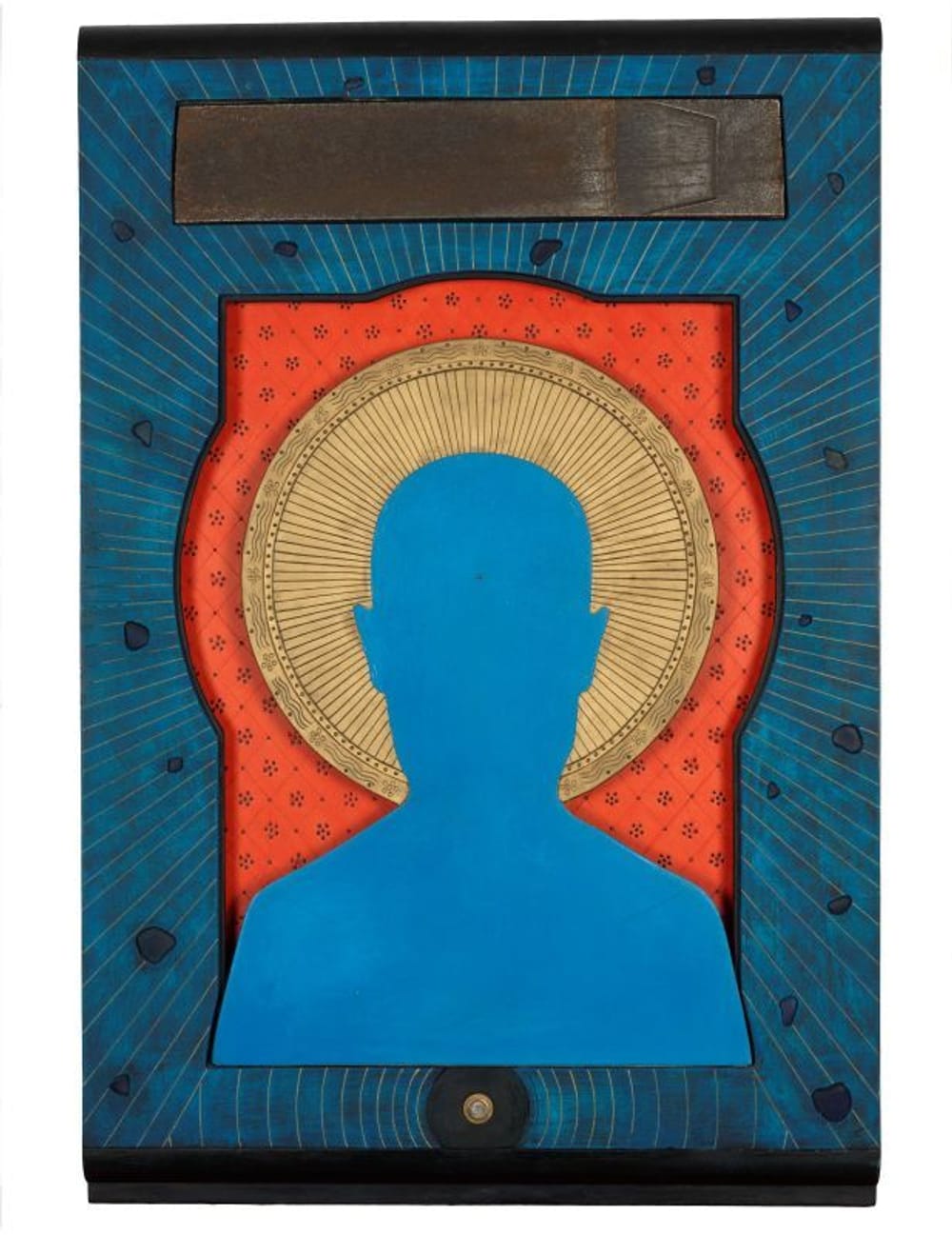

In Minich’s three-dimensional work Vermillion (1991), a bright blue silhouette of a head is superimposed on a golden halo. It’s as though we’re blocked by another viewer looking at an icon on the wall. In a blink, we notice that the blue noggin is perfectly centered, making our fellow viewer appear divine. And if they’re divine, maybe we…? The shift took me just a second; all I had to do was notice what was there.

Muinde and Minich thus offer useful approaches for those caught in the confusion Making Strange deliberately produces. Our approach to this art can be applied to anything we don’t fully understand: hold on and keep watching.

At top: Anne Minich’s 1991 Vermillion. (Image courtesy of PAFA.)

What, When, Where

Making Strange: Sacred Imagery and the Self. Through April 6, 2025, at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Samuel M.V. Hamilton Building, 118-128 North Broad Street, Philadelphia. (215) 972-7600 or pafa.org.

Accessibility

PAFA galleries in the Hamilton Building are accessible to wheelchairs and strollers at the Broad Street entrance, which is at street level. Wheelchairs are available at no charge on a first-come basis at the front desk. Accessible restrooms are located on each floor. For more information, call (215) 972-7600.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.