Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Chasing completeness

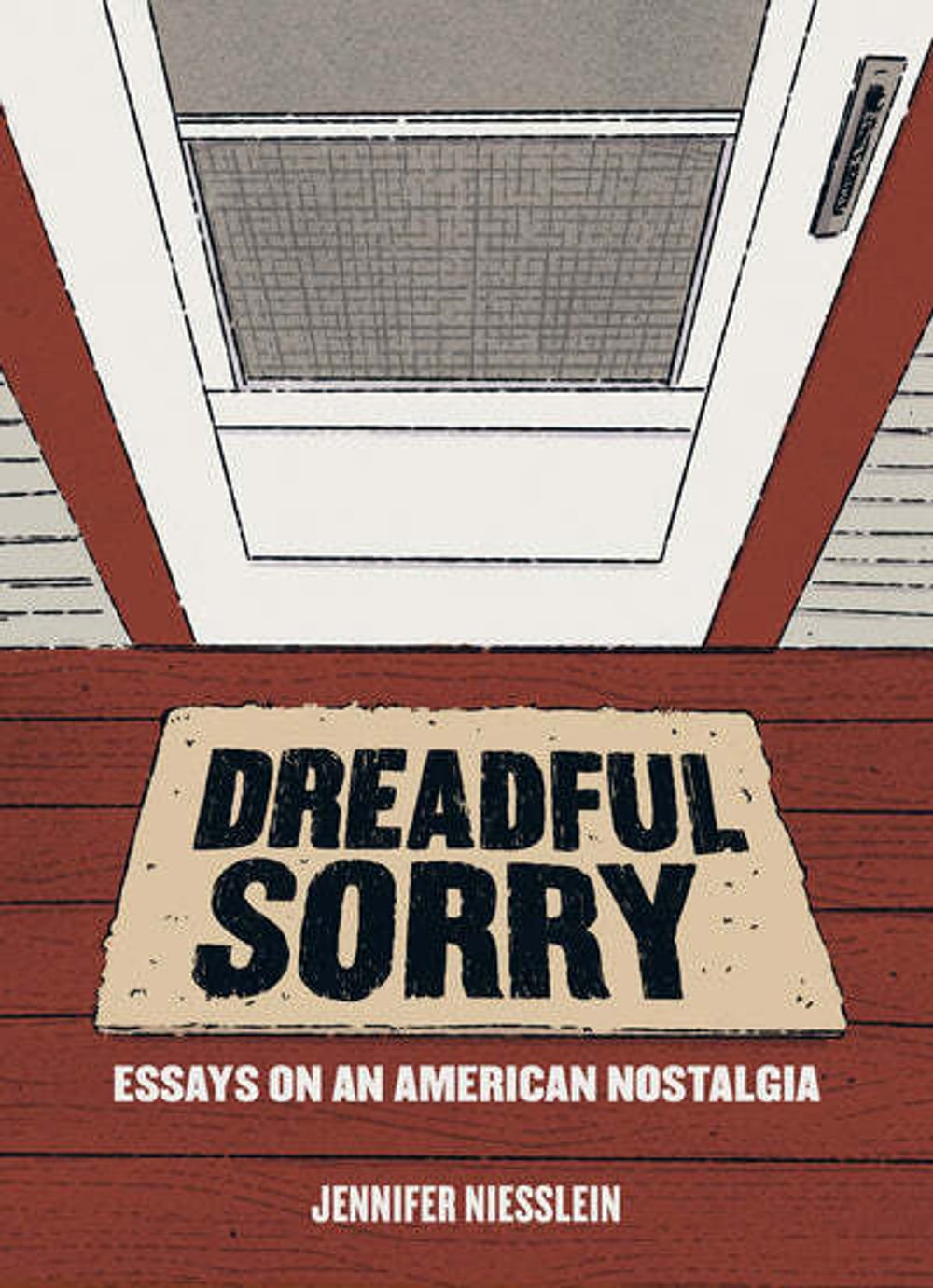

Dreadful Sorry: Essays on an American Nostalgia by Jennifer Niesslein

“I have a nostalgia problem, and I’m not the only American who does,” writes Jennifer Niesslein in the introduction to her candid and thoughtful new essay collection, Dreadful Sorry. Niesslein explores this problem, asking what it means to be nostalgic in a world where the feeling has been co-opted by those sporting “Make America Great Again” t-shirts. Is it possible to feel nostalgic for the past while working to create a better future?

Niesslein was born in western Pennsylvania and raised across the Rust Belt. Her family was firmly rooted in the white working class—her ancestors were Polish immigrants considered to be “the perfect fit for manual labor” by the white American elite. Niesslein opens this collection with the story of her great-great-grandmother, the first of her ancestors to come to America and a mythic figure in Niesslein’s life. She was a mother of four (one of whom was rumored to be mixed-race) who began bootlegging to support her family and was later murdered, her body found by a creek.

After this crime, the family fell into poverty, living in company housing and struggling to make ends meet—a cycle that Niesslein herself was one of the first to break. Examining the myth of her “bad-ass” bootlegging ancestors enables Niesslein to “click the lens away and transform nostalgia into plain-old history.”

"Mighty White of Me"

Each of the subsequent essays attempts to do the same: take on the personal, cultural, and political myths we hold and unpack the nostalgia surrounding them. In “New Galilee,” Niesslein brings her son and husband to the town where she formed her fondest memories, only to be reminded by her father that it was a time of intense financial strife. In “Little Women,” she rewatches the film with her beloved sisters and is forced to confront the possibility of a future where one of them is gone. And in “Mighty White of Me,” she strives to tackle the most insidious myth of all: whiteness.

Niesslein grew up in a white family in largely white spaces. When reflecting on whether she can remember hearing any racial slurs from her family members, she comes up blank. But she does not let herself off the hook, acknowledging that this gap in her memory is likely “a protective reflex to safeguard my nostalgia … a kind of white mental contortionism that my brain performs to make me believe myself unscathed by white supremacy.”

Trouble at Homestead

This same contortionism appears during a visit she takes to the Homestead, a luxury resort in Virginia established in 1766. She arrives just after the election of Donald Trump in 2016, and she finds herself sleeping with the myth of white southern hospitality. The only photos on the walls at the Homestead are those of white dignitaries, and any mention of slavery has been wiped away. The resort was even used as an internment camp for Japanese diplomats and their families during World War II. She asks, “What is the Homestead’s nostalgic draw except as a place where human rights were abused in the name of luxury?” And, “What is ‘Make America Great Again’ except nostalgia for a time when many Americans didn't have the rights they do now?”

I appreciate Niesslein’s candor and willingness to take on such deeply rooted American problems, but her commentary at times falls short of revelatory. At the Homestead, she wears, albeit skeptically, a safety pin (a symbol some used to show solidarity with marginalized people) as “a reminder to the other guests that they don’t own whiteness.” In “Mighty White of Me,” she admits to her past complacency and ends her commentary with a list of the ways she is now engaged in the fight against white supremacy. It’s reminiscent of a confessional Facebook post, or the shallow calls to wear a “pink pussy” hat in protest of Trump’s election—well-meaning, yet performative.

The end of the beginnings

But the true strength of Niesslein’s collection does not lie in her racial or political commentary, but rather in her deeply personal and lovingly written ruminations on her own memories. Of sitting with her husband and son in a park in her hometown, Niesslein writes, “I’m having a rare moment of seamlessness, the feeling that somehow Brandon and Caleb can really understand me now, seeing where I came from. I feel whole.”

Niesslein can recognize that this feeling of completeness is an illusion, but that doesn’t stop her from chasing it. She is at the age where there are no longer any “big beginnings,” living, instead, in the “squishy middle.” Writing these essays down is, in part, a way for Niesslein to give shape to the muddled moments of her life, to take apart the puzzle pieces of her memories and figure out how they fit back together.

Nostalgia as hope

Nostalgia is a comfort, but it is also a crutch. We hold on to our illusions of the past because they make us feel secure and “whole,” as if we can somehow stop time barreling forward, sending us into the unknown.

So what do you do, as a self-identified nostalgic?

In the final essay, Niesslein attempts to give us an answer. When she asks her son what he thinks about nostalgia, he says, “Isn’t part of nostalgia for a place meaning you love it enough to make it better?” It is a hopeful definition, and one I’d like to believe, or at least attempt. Can nostalgia be more than a regressive grip on the past? Can it, instead, be a form of active love? Niesslein says yes.

What, When, Where

Dreadful Sorry: Essays on an American Nostalgia. By Jennifer Niesslein. Cleveland, OH: Belt Publishing, March 1, 2022. 162 pages; paperback; $16.95. Get it on bookshop.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Grace Kennedy

Grace Kennedy