Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

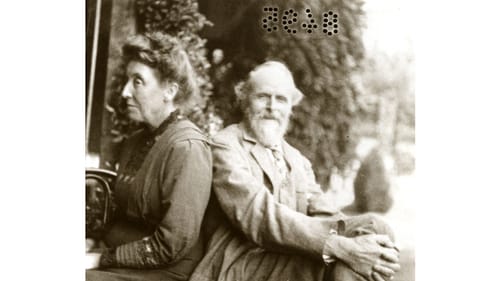

Rediscovering a Victorian power couple

Delaware Art Museum presents A Marriage of Arts & Crafts: Evelyn and William De Morgan

The Delaware Art Museum offers an opportunity to see art history in the making: a stunning exhibition of two influential Victorian artists lauded in their lifetimes but relatively unrecognized in ours. Astoundingly, A Marriage of Arts & Crafts: Evelyn and William De Morgan is the first exhibition of arts and crafts pottery maker William De Morgan (1839-1917) and Pre-Raphaelite painter Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919).

Organized by the museum over the past five years and making its debut there, this gathering of 77 artworks from the UK includes large paintings and fragile ceramics. The exhibition was a joint project of museum curator emerita Margaretta Frederick and Sarah Hardy, director of England’s De Morgan Foundation. The foundation has no building or permanent home, so though its holdings have been periodically displayed, this is their first dedicated exhibition. Extensive scholarship and curatorial savvy have brought this powerhouse couple to the fore. The De Morgans encouraged one another’s work as they moved in influential cultural circles, sharing an interest in spiritualism, women’s suffrage, and the social issues of their day.

A daughter and an artist

Born May Pickering, the artist changed her name to Evelyn (pronounced with a long “e”), a gender-neutral moniker at the time, in order to sidestep prejudice against women in the arts. Influenced as a child by the often-morbid tales of the Brothers Grimm, she was educated alongside her brother, unusual for the times. Though her mother “wanted a daughter, not an artist,” her father encouraged the young woman and supported her painting career. Taking inspiration from Botticelli for her symbolic works, Evelyn excelled in anatomical drawing (something not thought proper for a lady), characterization, and a masterful handling of drapery.

These strengths are apparent in her works. Her pencil drawing Head of Jane Morris in Old Age (1904-05) is a sensitive tribute to that famous doyenne of the Pre-Raphaelite world. Deeply felt portraiture abounds in her paintings as well, also remarkable for the feminist subject matter swathed in Evelyn’s classical handling of lush textiles, seen especially in The Gilded Cage (1900). Her lifelong interest in spiritualism is apparent in Earthbound (1897) and others, but the exhibition’s most remarkable painting is Flora (1894). Overwhelmingly beautiful, and simply overwhelming, this almost life-sized personification of spring nearly steps off a huge canvas. Evelyn frequently utilized gold paint, and here, under the exhibition’s perfectly calibrated lighting, the work glows with virtuosity and joy. It’s a showstopper.

A lustrous reinvention

William Frend De Morgan created brilliantly colored tiles, pots, and plates with distinctive, shimmering luster-ware surfaces. He was brought up by his mother, a practicing medium, and studied at Britain’s Royal Academy, becoming friends with Burne-Jones (one of the era’s great painters) and arts-and-crafts pioneer William Morris. Beginning his career in stained glass, William noticed that when certain glass paints were fired, they gained an unexpected luster, which piqued his scientific curiosity. He built a kiln in his rented house (actually, he set the house on fire) and began to craft the exceptional ceramics that would become his life’s work.

William was celebrated as a ceramicist, taking multiple commissions and designing tiled interiors. But his most remarkable achievement was to reinvent the lost art of Persian lusterware, a delicate and unpredictable process that requires multiple firings, each fraught with the possibility of destruction. His works—ewers, bowls, and tiles, many made between 1898-1907—often feature anthropomorphized animals: Antelope and Fruiting Tree Dish shows a shy antelope observed by a sly lizard. One of the most remarkable pieces in the exhibition is Moonlight Lustre Galleon Punchbowl. Its blue “moonlight suite” of three glazes is the pinnacle of his artistry, an amazing feat of ceramics chemistry that remarkably survives in perfect condition to dazzle us still.

A stunning first-time exhibition

Their work was shepherded during the couple’s lifetime and after their deaths by the De Morgan Foundation, created by Evelyn’s long-lived sister Wilhelmina Sterling (1865-1965). Sterling wrote a book about the couple (one of the few works of scholarship until the museum’s publication) and was a lifelong advocate for the acquisition and protection of their works.

In the exhibition, their works are displayed to perfection by Keith Ragone, noted for his elegant and sensitive design, who created a period ambiance to match the lustrous ceramics glazes and the glow of the gilded paintings. The exhibition also includes rare books and autographed letters from the University of Delaware’s Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. There is a scholarly publication, edited by Dr. Frederick and published by Yale University Press, and upcoming programs include a new Pre-Raphaelite art history course (in person and virtual) and weekly tours.

After it closes in February, the stunning exhibition travels to the Crocker Art Museum (Sacramento, California) and the Museum of Fine Arts (St Petersburg, Florida). Also inaugurating the museum’s “Year of the Pre-Raphaelites,” through February 5 a smaller exhibition on the second floor, titled Forgotten Pre-Raphaelites, highlights American painters of the same period with works from the museum’s permanent collection.

What, When, Where

A Marriage of Arts & Crafts: Evelyn and William De Morgan. $6-$14 (free for kids under 6). Through February 19, 2023 at the Delaware Art Museum, 2301 Kentmere Parkway, Wilmington. (302) 571-9590 or delart.org.

Accessibility

Masks are optional inside the museum, but required in the auditorium, on tours, and in studio classes.

The museum and Copeland Sculpture Garden are wheelchair accessible, with free parking and a barrier-free entrance. Wheelchairs are available; personal care attendants admitted free.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder