Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Revealing Philadelphia’s almost-invisible past

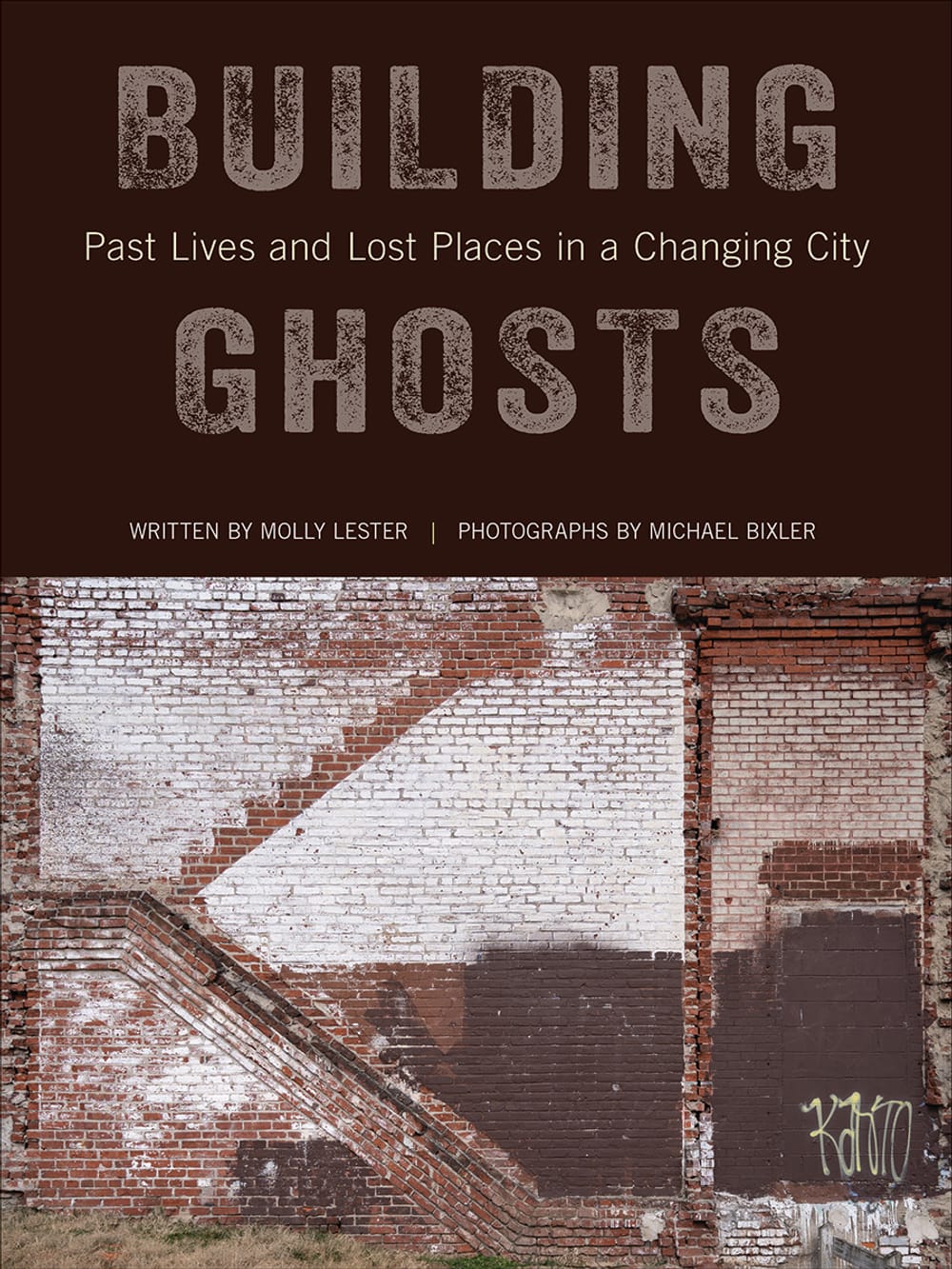

Building Ghosts: Past Lives and Lost Places in a Changing City, by Molly Lester and Michael Bixler

Molly Lester and Michael Bixler spent the pandemic hunting ghosts. In Building Ghosts: Past Lives and Lost Places in a Changing City, they make a compelling case for visiting sights that aren’t on any “must see” list.

Lester, an architectural historian and associate director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Urban Heritage Project, and Bixler, editorial director and chief photographer for Hidden City Philadelphia, sought “building ghosts”: imprints of demolished buildings on walls they once shared with neighboring structures. Architecturally speaking, Philadelphia, with plenty of party walls and a penchant for demo, is thoroughly haunted.

A ghost’s lifespan depends on its location. Those on parcels that interest developers vanish quickly. Others remain for years, becoming part of the urban landscape.

Over four months in late 2020, Lester and Bixler documented 194 building ghosts, a count that fluctuated even as they searched. Eighty-one are depicted in the book, half of them profiled by Lester, who dove deep into public records to uncover the stories. Each chapter begins with a map plotting building ghosts in one geographic section, along with a discussion of the area's history and incidence of ghosts.

Structural racism

North Philadelphia has the most building ghosts, due to neighborhood age and racist practices by realtors, lenders, and neighbors to segregate Black and Jewish people looking to buy or rent homes. Exacerbated by poverty over decades, structures fell into disrepair, sometimes leading to collapse or, if deemed public hazards, demolition.

From 2010 to 2020, Philadelphia demolished all or part of almost 5,500 “imminently dangerous” buildings for public safety. Of those, 56 percent were in North Philadelphia, though it had just 14 percent of the city’s buildings. “When they are the work of the city—with nothing constructive introduced in their place—building ghosts are evidence of collective failure, not success, in a neighborhood,” Lester writes.

In Strawberry Mansion, 2546 North 28th Street was part of a group of homes owned by neighbors who in 1923 signed an agreement “not to grant sell or convey lease or sublet … to any member of the negro race.” The covenant, filed with the city, was deemed legal until 1948 when the US Supreme Court reversed its own earlier ruling allowing the practice, which violates equal protection under the Constitution’s 14th Amendment.

Retail legacies

Building ghosts reveal the legacies of small shops that once anchored neighborhoods. A jeweler lived and worked in the last half of the 19th century at 519 South 4th Street, a typical residence-over-shop in Center City. In 1903, the property became home to a baker, his family, and their boarders, and in the 1940s, 519 was purchased and torn down by Israel Forman, who built a Kosher meat company that operated into the 1970s. The Formost Provisions building still stands, but gaze above its second floor to spy the ghost of the original three-and-a-half-story structure.

Few ghosts inhabit Northwest and Northeast Philadelphia, for different reasons. The Northwest has more single homes, so fewer party walls. The Northeast’s housing stock is newer, constructed for post-WWII homebuyers who, tending to be middle-class and geographically stable, made that swath of the city less susceptible to rapid turnover, invasive development, and structural decline.

Undocumented lives

Shadowy building ghosts represent generations who lived, worked, died, and sometimes were themselves invisible. Lester notes that official records can be spotty, particularly for Black and female property owners. Take 2327 West Oxford Street (circa 1876), well documented until 1923, when the white Gourleys sold to the Black Montgomerys, at which point, coverage in the Philadelphia Inquirer dropped off. Lester picked up the trail, however, in the pages of The Philadelphia Tribune, the nation’s oldest continuously published paper covering African Americans.

Poor neighborhoods have less political influence, making them vulnerable to zoning permitting industrial, sometimes environmentally dangerous, businesses to move in. This happened in South and Southwest Philadelphia, as well as North Philadelphia.

At 5247-5251 Whitby Avenue, Lester and Bixler found the ghost of a 75-car automotive garage and mechanic shop constructed in about 1925, an example of the dirtier businesses that congregated in the southwest and lower river wards. Unusually, the garage was built and operated by a divorced woman, Florence Stockton, who hired builders, mechanics, and salesmen in what was then a young automotive industry. She even sold an innovative new paint that enabled buyers to choose their car’s color, instead of settling for the universal black. Surprisingly, in 1926, Stockton sold the property and disappeared from official records.

Buildings crumble, art breaks out

In South Philadelphia, Lester and Bixler encountered ghosts gussied up with spontaneous art. A bistro set was graffitied on the remains of 1600 South 24th Street, which is appropriate: while it stood (1909-2000), 1600 contained a butcher shop and after that, a grocery wholesaler.

In Philadelphia, even sound buildings become canvases. Isaiah Zagar’s sparkling mosaics appear in the unlikeliest places, and in the 1980s, the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network was established to better channel wall writers’ impulses. That program sowed the seeds for the internationally known Mural Arts Philadelphia, the nation’s largest public art program, which creates colorful, community-based wall art across the city.

Lester proposes that building ghosts are themselves a form of wall art: “Philadelphia’s montage of building ghosts … pierces the liminal space between the city’s creativity and its destructiveness. With these party walls … the city has inadvertently fostered public art of a different sort, a series of accidental creative works interspersed with more deliberate canvases.”

Grasping a history we barely know

Even in its historic heart, Philadelphia has been inexplicably slow to value preservation over destruction, but Lester points to hopeful signs, including loan programs for city homeowners and small landlords to make repairs. In 2021, a University of Pennsylvania study found that repairing one home under the Basic Systems Repair Program, which funds free repairs to major home systems (roof, plumbing, etc.), was associated with a 22 percent decrease in crime on the home’s block.

By capturing images and details of structures’ interior lives—the sawtooth silhouette of a missing staircase, the outline of a lost bedroom closet, the hint of an absent fireplace—Building Ghosts grasps the last wisps of a history we barely know. The memories, if not the buildings themselves, are surely worth preserving.

What, When, Where

Building Ghosts: Past Lives and Lost Places in a Changing City. By Molly Lester; photography by Michael Bixler. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2024. 288 pages, hardcover; $40. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.