Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

From page to screen, to page again

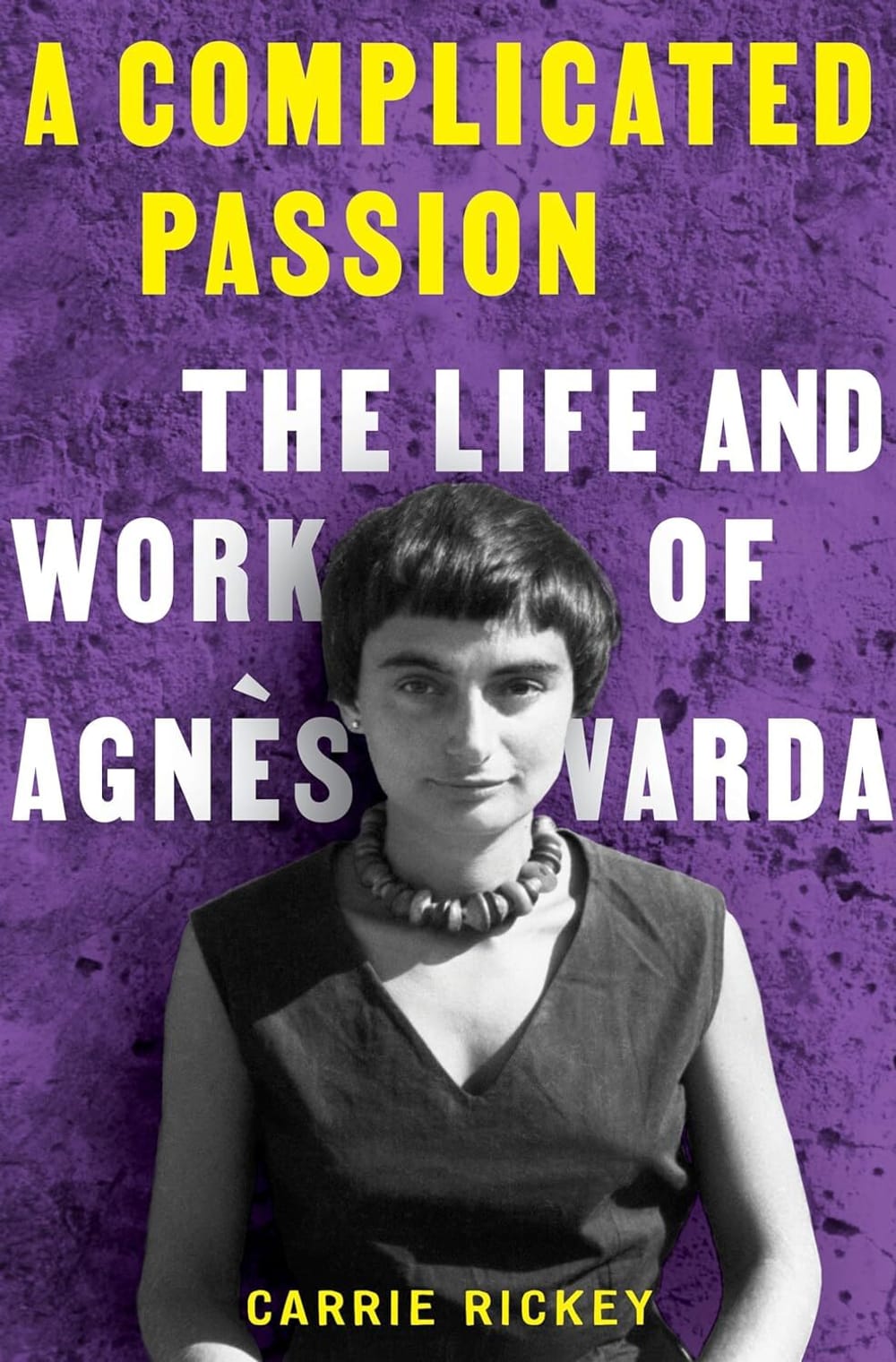

Capturing film legend Agnès Varda with Carrie Rickey's A Complicated Passion

With a career that constantly evolved over more than six decades and included directing such classics as Cléo from 5 to 7 and Vagabond, French director Agnès Varda gets an English-language biography courtesy of former Philadelphia Inquirer film critic Carrie Rickey.

It's a known injustice that many great artists have gone their lifetimes without knowing how much future generations would revere their work. Fortunately, that wasn't the case with director (and all-around artist) Varda, who was finally given her flowers, including an honorary Oscar, before passing away from breast cancer in 2019. It took long enough, though, for her many contributions to cinema to be recognized. From being an early adopter of the digital camera to kickstarting the French New Wave, Varda's accomplishments and backstory are finally being recorded in Rickey's new book, A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda. Rickey (who resides in Philadelphia and has written for outlets including Artforum and Film Comment) answered some questions about the biography.

Rachel Bellwoar: Having written about film for years (including 25 years for The Philadelphia Inquirer), what made you want to write your first book, and were you always committed to Agnès Varda as your subject?

Carrie Rickey: Every journalist thinks she has a book in her. In 1996, I had signed on to write a biography of Doris Day but returned the advance when my husband and I suddenly were able to adopt a baby. I had floated some ideas to publishers about writing the story of female filmmakers who, 100 years ago, were flourishing in America, Australia, and France but inexplicably erased from movie history. In 2020, a few weeks before the Covid directive to stay at home, I was approached by Paul Bresnick, an agent wondering if I wanted to write a proposal for a Varda bio. Given that most of my journalism outlets were drying up, I thought, well, I love Varda's movies, and this would satisfy my interest in how directors like Agnes Varda, Gina Prince-Bythewood, Ava DuVernay, Kathryn Bigelow, etcetera, fought for their space in a profession dominated by men.

Once, when reporting the shockingly low percentage of women working as directors in the US (then about five percent) in, I think, 2008, I phoned the Philadelphia Bureau of Labor Statistics to talk about the low number of female filmmakers. The woman I spoke with told me that, "The two professions with the lowest number of working women are coal miners and film directors." I have both a stepdaughter and a daughter and believe that for young girls, seeing the world through the eyes of a woman enables them to see women who are not sexually objectified and have meaningful work.

Bellwoar: Besides being very open to interviews throughout her life, Varda wrote a memoir and directed multiple autobiographical features. What additional insight do you feel a biography brings to her story?

Rickey: If you read Varda's 1994 memoir, which is non-chronological and more like an annotated photo album than a memoir, you find huge gaps in her history. I wanted to fill those gaps.

Bellwoar: While lack of material wouldn't seem to be a problem with Varda, one obstacle that does come to mind is language and access, depending on if you were able to travel to France and Belgium. Did you have any issue finding footage or translated documents when researching her life, and do you speak French?

Rickey: Fortunately, just when I signed the book contract with Norton, Criterion announced that it was assembling a box set of all her films, so I had easy access to her complete works. Unfortunately, it took two years before I could travel to France and Belgium. A wonderful Varda scholar named Kelley Conway at the University of Wisconsin connected me with Bernard Bastide, who assisted Varda on the 1994 memoir and had organized her archive. He was an enormous help. I do not speak French fluently. (My first language was Spanish, and I just couldn't get my mouth around French pronunciations and ended up taking German in high school.) Varda's son and daughter were helpful at first but wanted to do their own book, which I completely understand. I used the advanced translator, DeepL, which, belatedly, helped me learn French without having to pronounce it correctly. I was also lucky to live in Philadelphia, where Patty White of Swarthmore and Homay King of Bryn Mawr live (within a few blocks from me), and Varda scholar Sandy Flitterman at Rutgers was available. These four generous women served as a Varda "swat team" to suggest interpretations of her life and films that often differed from my own.

Bellwoar: In the introduction, you explain that the title, A Complicated Passion, came from an interview you did with Varda in 1988, where she used that phrase to describe her marriage to director Jacques Demy. Why do you feel that phrase applies well to her career as a whole?

Rickey: I hadn't understood that the French New Wave was financially successful for only three or four years, roughly 1959 to 1963, by which time the only directors lucky enough to continue to find consistent funding were men. Varda had a much more challenging time getting money than, say, her husband, Jacques Demy, Francois Truffaut, or Jean-Luc Godard. She was passionate about making movies, but the ones she made in the early part of her career were, at best, modest successes. Movie producers didn't always reciprocate her passion, and she found her own way of making films with a different model. Beginning with Vagabond, she had a script outline and woke up early every morning to write the dialogue for the day.

Bellwoar: Cléo from 5 to 7 was the first film of Varda's that you watched, but is there one that you’ve returned to the most?

Rickey: My five favorite Varda features are Cléo, Le Bonheur, Vagabond, The Gleaners and I, and The Beaches of Agnes. All so unique and artisanal.

Bellwoar: Unlike most of her peers, Varda wasn’t a cinephile when she took up directing. Do you think that’s something modern film students could learn from?

Rickey: It's true—Varda, who was a still photographer before she made her first film in 1954/1955, had developed her own singular visual language on her own and wasn't compelled to quote other filmmakers [like] Godard and Resnais did.

Bellwoar: While documentaries and narrative features are usually kept separate, Varda didn’t make that same hard distinction. Is that still rare today, or have other documentarians followed suit?

Rickey: Isn't every movie in part a documentary of its time and place? She knew that. I do think that Gleaners had a powerful influence on the work of other documentary-makers.

Bellwoar: Starting with her first film, La Pointe Courte, Varda would use filmmaking as a means to deal with death. How much do you think grief drove and colored her work?

Rickey: Certainly with La Pointe Courte and the trio of films about her late husband. And her film Documenteur, which she made when Demy left her for another relationship.

Bellwoar: Some of my favorite stories in A Complicated Passion include finding out that Varda’s first paid photography job was taking photos of children with Santa Claus and learning how Varda convinced Alain Resnais to edit her first feature. Do you have a favorite anecdote of the ones you discovered?

Rickey: As her son, Mathieu, said at her burial, "She could convince you that the glass was full when it was half empty." She had such moxie. She had the enviable capacity to project absolute certainty. Resnais was flabbergasted when she timed and numbered thousands of feet of footage from La Pointe Courte in a matter of days and realized that she was serious. When Demy was courting Michel Legrand to write the music for The Umbrellas of Cherbourg and the composer initially declined, it was Varda who convinced Legrand to take on the project.

What, When, Where

A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda. By Carrie Rickey. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2024. 288 pages, hardcover; $29.99. Get it here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Rachel Bellwoar

Rachel Bellwoar