Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

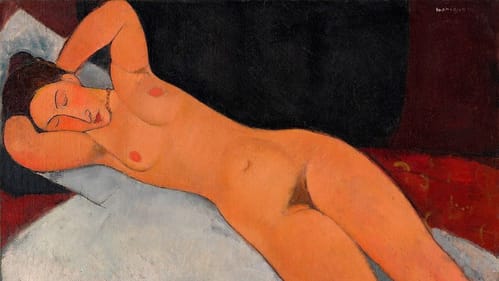

Expanding the Modigliani canon?

The Barnes Foundation’s Modigliani Up Close will feature newly examined paintings

The sinuous nudes and luminous portraits created by Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) appear deceptively simple, seducing forgers since the Italian artist’s death in Paris at age 35. His work is among the world’s most valuable and most often faked. Wouldn’t it be great if we had a reliable list of Modigliani’s artworks? Well, we don’t.

A catalogue raisonné (CR) is a verified list of every work by a given artist. Modigliani has five, and none of them are correct. Each has problems like questionable scholarship, very few photographs of the artworks, or inclusion of obvious fakes. Only the CR by Milanese critic Ambrogio Ceroni (1907-1970), which lists 337 paintings, is generally trusted. The problem is, scholars believe as many as 80 additional Modigliani paintings exist. But which ones are they?

This year, the Barnes Foundation identifies four likely candidates in Modigliani Up Close, an exhibition opening on October 16. That’s big news, especially because Nancy Ireson (deputy director for collections and exhibitions and Gund Family chief curator at the Barnes) and Simonetta Fraquelli (an independent curator) are among the leading advocates of forensic studies of Modigliani works. Their choices for this show carry a great deal of weight.

"A judgement call"

“There are four paintings not in Ceroni in our exhibition,” Ireson told BSR, “all of which underwent the same rigorous research and technical analysis as other works on display. Stylistic similarities are clear, but for art historians, visual assessment is a judgment call.” Among 47 paintings and sculptures in Modigliani Up Close, the Barnes will display four newly considered paintings: Tate London’s Madame Zborowska (1918); Guggenheim New York’s Portrait of a Student (c. 1918-19); Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Portrait of a Polish Woman (1919); and privately owned Portrait of Thora Klinckowström (1919).

A lot has changed since late 2017, when Ireson and Fraquelli co-curated a massive retrospective of 100 works, Modigliani, at the Tate. “Everything on display in this show is from Ceroni,” Ireson told Ilze Pole for Arterritory in 2018. “Other organizations could try to expand the canon, but, as a public museum, we have a public trust. We had a very conservative view about what we would include in the show.” (A 2017 exhibition at the Palazzo Ducale in Genoa was less careful: it included 20 Modigliani forgeries and closed in disgrace.)

Since then, scholars have completed a number of Modigliani studies, using X-rays, infrared reflectography, ultraviolet photography, light microscopy, and paint chemical analyses using X-ray fluorescence. The French government tested its publicly owned Modigliani paintings and sculptures, displaying the results in Les Secrets de Modigliani, which opened in early 2021 at Lille Métropole Musée d’Art Moderne. In London, the Tate’s Modigliani Technical Research Study was led by Ireson and Fraquelli. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, and the Barnes in Philadelphia, have tested their works as well. Results were reported extensively in The Burlington Magazine (March, April, and May issues, 2018) and noted in The Art Newspaper, but the exhibition at the Barnes is the first American exhibit to explore the new discoveries.

Beyond the last self-portrait

Modigliani Up Close highlights the recent technical studies of the artist’s paintings, sculptures, and drawings that placed Modigliani works under a microscope, literally. Focusing on the physical objects, Ireson and Fraquelli organized Modigliani Up Close

with conservators Barbara Buckley, senior director of conservation and chief conservator of paintings at the Barnes, and Annette King, paintings conservator at Tate, London. Says Fraquelli, “Our conversations over the years that led to this show have given us a far deeper understanding than any of us could have gained working alone: there are more than 50 authors for the exhibition catalogue.”

The curators downplay their inclusion of the four non-Ceroni paintings labeled as by Modigliani in the exhibition catalogue (though according to the Barnes, the exhibition's wall text notes that the research on these pieces was inconclusive), and beyond this, Modigliani Up Close is a terrific exhibition. The loans to the show are so magnificent that the 12 Modigliani paintings belonging to the Barnes (it’s tied with the National Gallery of Art for the world’s largest Modigliani collection) remain in their usual places in the permanent exhibition. Many of the loans have not been seen in Philadelphia before, and two are especially beguiling.

Jeanne Hébuterne, Seated (1918), owned by the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, was last seen in the US in 1971. The most enigmatic portrait is of Modigliani himself, holding a palette loaded with the colors he’s using in Self Portrait (1919). It belongs to the Museo de Arte Contemporâneo de la Universidad de São Paulo in Brazil and hasn’t been shown in the US since 1951. Modigliani hardly ever painted self-portraits, and this was his last.

A vulnerable legacy

One reason so many forgeries of Modigliani’s work exist is that after he died in Paris on January 24, 1920, no one had the authority to protect his legacy. His pregnant companion, Jeanne Hébuterne, died by suicide the next day. Their only child, Jeanne, born in 1918, was adopted and raised in Italy by her father’s family.

Modigliani’s artwork belonged by agreement to the gallerist who had supported him, Léopold Zborowski, so his reputation was informally in the hands of his Paris art dealers. They also died young: Zborowski in 1932, and Paul Guillaume in 1934. By then, forged Modiglianis had begun proliferating, a problem worsened by the chaos of World War II. Besides the artworks themselves, photographs from shows, lists of works, and sales records were scattered, leaving myriad opportunities for forgers, whose work is a con on the viewer and a crime against the artist.

The dangers of verification

The best defense of an artist’s reputation is a reliable, complete CR, listing every artwork by the artist, supported by verified documentation (ownership, exhibition, and condition history) and color photography. The International Foundation for Arts Research (IFAR) collects information about existing and in-progress CRs; details about the five Modigliani CRs, published from 1929 through 2012, and two active projects, are on IFAR’s website.

The most recently published author there, Christian Parisot, has been repeatedly accused of fraud and forgery; a 2008 conviction was overturned on appeal. Modigliani’s daughter Jeanne, who died in 1984, allegedly gave Parisot droit moral (moral rights) to thousands of documents related to her father. Only Parisot knows where they are. In 2014, one of Modigliani’s two granddaughters tried to reclaim droit moral and control of the archive from Parisot; incredibly, an Italian court ruled against her.

Knowing that Ceroni is incomplete leaves a number of collectors and institutions holding artworks that might be genuine. The most promising of these deserve the chance to be proven. However, owners risk a great deal by investing in the expensive, time-consuming process. If the artwork can’t be verified, the owners lose millions of dollars, possibly in the price they paid and surely in the price they’ll never get. Plus, suspicion falls onto their entire art collection. Picture the angry owner whose $50 million painting is now worth very little, and you can practically hear them summoning their lawyers to sue everyone involved.

The CR revolution

Just as technology has changed how art is examined, it has revolutionized the way CRs are created. Digital CRs are growing more popular: they’re much less expensive to produce than books (though still not cheap), and because they’re databases, objects can be sorted by owner, exhibition, subject, year created, and more. Unlike books, they’re easily updated. Some of the databases are designed to be exported to a publisher, so scholars can print traditional CR books and continue updating their research online.

The art world now prefers teams of experts, rather than a single author. These committee members look at the artwork in person, ideally in a group including known works by the artist. They check its ownership history (provenance) and documentation: for instance, are there photographs of it in a show during the artist’s lifetime? Using scientific testing and imaging, the paint, what’s underneath it, and its support (canvas, panel, cardboard) can be compared with materials the artist was known to use, or were available. When all of the research is complete, the committee members contrast any red flags with the attributes in a work’s favor. Then, they vote. Rarely will a single scholar “authenticate” a painting by Modigliani, although they will cry fake if they suspect one. Rather, they say it appears to be correct. Nobody wants to be sued, harassed, or even ensnared as a witness in drawn-out litigation and appeals.

Two new CRs

Besides the five published Modigliani CRs, there are two in progress, each led by well-known scholars. Marc Restellini, based in Paris, announced his CR project in 1997, with support from Wildenstein-Plattner Institute (WPI). They parted ways in 2014, and litigation between Restellini and WPI is ongoing. Restellini, who curated a Modigliani exhibition at the Albertina Museum, Vienna, in 2021, says his CR will be published in six volumes next year, followed by an online version.

“Surprisingly, the curators did not contact me for [the Barnes’s] exhibition,” Restellini tells BSR, “while I have been studying, analyzing, and documenting in detail how Modigliani created his works over the past 30 years. I appreciate that public institutions get together to study Modigliani’s œuvre. However, they refuse to collaborate with private institutions and collections, which I regret, as this does not contribute to progress in knowledge of Modigliani’s art.”

Kenneth Wayne has also studied Modigliani for decades; he curated Modigliani & the Artists of Montparnasse, which traveled to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art after opening in 2002 at Buffalo AKG Art Museum, New York. He works with a committee.

“Discussions with fellow Modigliani experts are interesting,” says Wayne, “and we only accept a work if we’re unanimous in our thinking that it’s correct.” The Modigliani Project, which Wayne founded in 2013, publishes images, exhibition history, and provenance of newly accepted works on its website. He says they’re not building a whole new CR in the traditional sense: “We’re adding to Ceroni, who said himself that his catalogue was incomplete.”

Working with Modigliani

Among the Modigliani-related programs at the Barnes is a January 2023 symposium, and neither Restellini nor Wayne have been invited. Asked why, the co-curators responded that Modigliani Up Close and its catalogue are about “understanding Modigliani’s working practice,” and the symposium will feature the show’s participating art historians, conservators, and conservation scientists. “The exhibition and its curators are not involved in any catalogue raisonné projects,” they said.

In the movement for team-based research, there is hope for clarity around Modigliani. Hurdles abound, like persuading private collectors to submit their works, shielding workers from litigation, and soothing dissension among Modigliani experts. But the artist’s legacy deserves better than it has received at our hands for the past century. In the meantime, whether you visit the exhibit for the technical studies, the exquisite artwork, or both, Modigliani Up Close will be a stellar show and a worthy setting to consider the four newly anointed paintings.

Disclaimer: The author is a member of the Catalogue Raisonné Scholars Association and a former freelance assistant at The Modigliani Project in New York City.

Editor's note: A previous version of this story characterized the four non-Ceroni paintings as additions to the Modigliani canon by the Barnes curators; they maintain that their intent is to promote discussion on assessing Modigliani, not make new determinations.

What, When, Where

Modigliani Up Close. October 16 through January 29, 2023, at the Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. $30 (good for 2 days). (215) 278-7000 or barnesfoundation.org.

Face masks are welcome, but not required.

Accessibility

The Barnes is a wheelchair-accessible venue; it offers free admission for personal care attendants and ACCESS/EBT cardholders.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Emily Schilling

Emily Schilling