Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

This art crime will produce nothing but victims

Barnescam: or, how to steal $20 billion

Enron? Tyco? Refco? For sheer chutzpah, political jobbery, legal manipulation, and creative accounting, the coup against the Barnes Foundation and the potential theft of its great gallery art collection is in a class by itself.

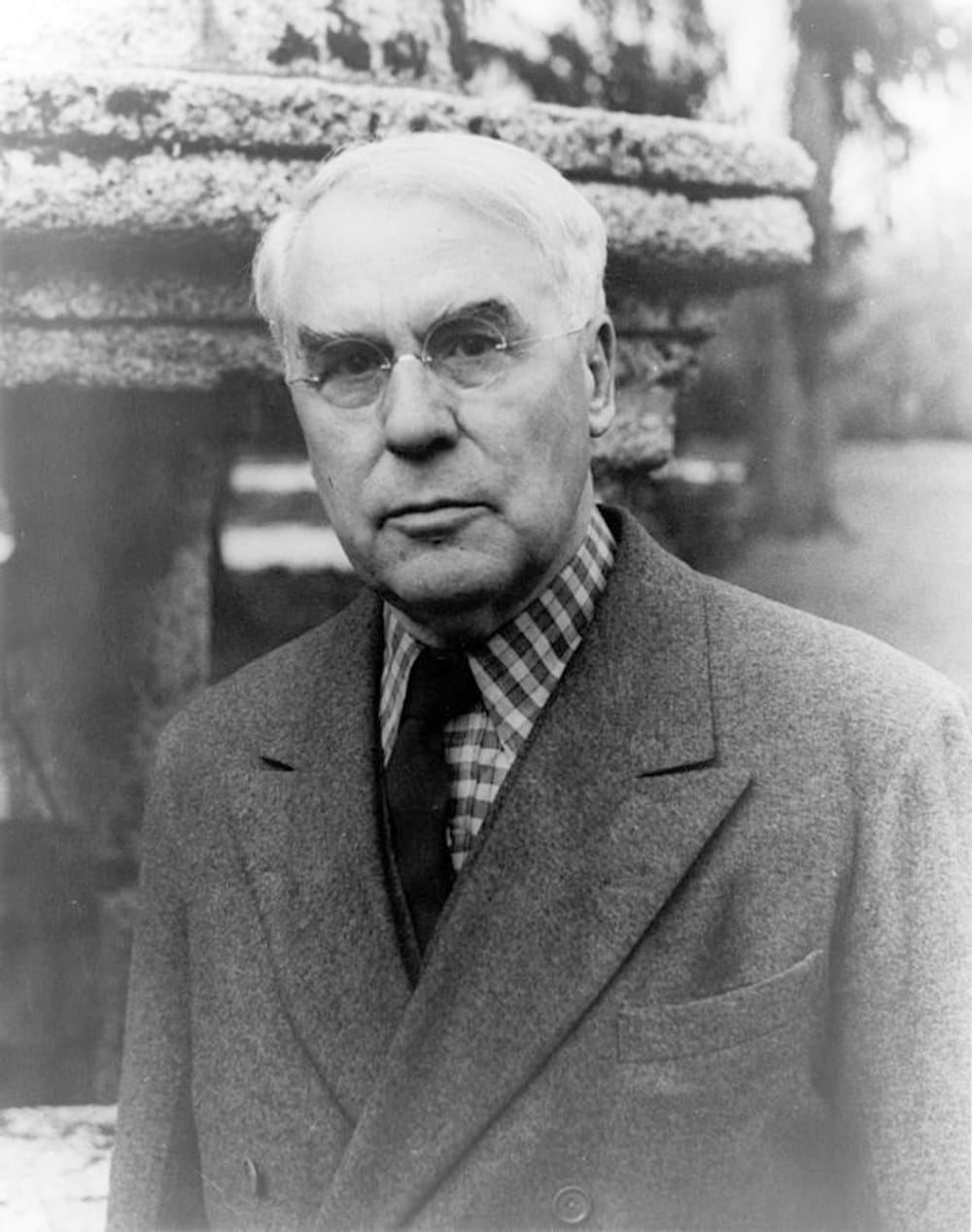

The story goes back to the infighting between the late Albert C. Barnes and the Philadelphia establishment in the 1920s and 1930s, when, shortly after setting up his foundation as a nonprofit educational institution for the betterment of the masses through art education, Barnes quarreled with the Museum of Art and crossed swords with Walter H. Annenberg, the publisher, quondam diplomat art collector, and eminence grise whose influence, even today, seems scarcely diminished by the grave. The details need not detain us; suffice it to say that, at a time when, for most Philadelphians, John Singer Sargent seemed the apex of daring and modernity, Barnes was collecting an unrivaled trove of Cézannes, Matisses, and Renoirs. These he used as the basis of an art program based on his own aesthetic principles.

After Barnes's death and that of his wife, Laura, his foundation passed under the nominal control of Lincoln University, a Black institution that Barnes selected in part because of his sympathy for the oppressed, his admiration for African art, and his desire to spite the local poohbahs. Barnes further instructed that the art contained in the foundation’s galleries—the choicest part of his collection, although a small percentage of the whole—be maintained in perpetuity, never to be sold, loaned, commercially reproduced, or even rearranged on the walls. As far as lay in his power, he wished to stop the clock with his death, and to keep his collection from the hands of the art world’s promoters, bounty hunters, and curatorial flacks. Above all, he wished to keep it out of the hands of Walter H. Annenberg, who, for 50 years after Barnes’ death in 1951, sought to obtain control of it.

Annenberg mounted a series of challenges to the Barnes trust through obliging proxies, including Pennsylvania’s then-deputy attorney general, Lois G. Forer, and the Philadelphia Inquirer, which Annenberg then owned (and, on the subject of the Barnes, still seems to). Under his prodding, a ruling was obtained from Judge Michael Musmanno construing the foundation to be a “museum” rather than a private educational foundation, thus requiring public access in order to maintain its tax-exempt status. The public was duly admitted at specified hours, beginning in 1961, and its access was increased over the years.

Still, the Barnes retained its fundamental character. The Lincoln trustees were silent partners, and the foundation was run by Barnes’s confidante and successor, Violette de Mazia. The collection had (as before) great cachet among art cognoscenti, but the general public had little awareness of or interest in it, and, after the initial flurry of publicity at its opening, the Barnes Foundation sank again into happy obscurity.

Thus it was when I first visited it in the late 1980s. Admission was a dollar; one simply paid at the gate, walked in, and, virtually undisturbed, had one of the world’s great collections of art at one’s disposal.

All of this changed with De Mazia’s death in 1989. A politically connected Center City attorney, Richard H. Glanton, became president of the Lincoln board and de facto director of the foundation. If the Barnes had been in fiscal distress prior to his arrival, no one had ever given indication of it. It had operated, at modest cost and within the bounds of its indenture, for more than 60 years; it had coexisted amicably with its neighbors on the quiet residential street of Latch’s Lane in Lower Merion, who were (and are) proud of its presence in their midst; it had never appealed for funds.

It was true that the restrictions Barnes had placed on investing its endowment had depleted its reserve; true as well that the collection lacked proper security and conservation. The proper recourse for that, however, was a funding campaign. Glanton spoke grandly of raising a $50 million endowment but did nothing to accomplish it. Instead, he pulled the emergency cord.

To Glanton, Lincoln was sitting on billions of dollars of unexploited capital. His goal was to turn the Barnes into a cash cow by raising its profile, opening its doors and marketing its product. Judge Musmanno had said the Barnes was a museum. Thirty years later, Richard Glanton was determined to make it one.

Glanton was not content to advertise. Declaring the Barnes to be in financial crisis, he announced his intention to auction off part of the collection. When curators and art scholars around the country protested that selling assets to pay current expenses was contrary to all sound museum practice, Glanton, happy to have it both ways, reminded them that the Barnes was a private foundation and made its own rules. He did not mention that the indenture of trust forbade him to sell any part of the gallery collection.

Glanton’s fire sale was only a ploy; his real objective was to gain permission from the Barnes’s judicial overseers to mount a round-the-world tour of French masterpieces from the gallery. This, too, violated the founder’s indenture, but Judge Stanley R. Ott of the Montgomery County Orphans Court granted a waiver, with lobbying support from the Philadelphia Museum of Art and behind-the-scenes maneuvering by Walter Annenberg. The PMA’s quid pro quo was to be its designation as the last stop on the tour, an absurdity given the fact that the entire Barnes gallery had been closed for two years and would remain so through the PMA exhibition, though the foundation was only five miles away. The PMA included Georges Seurat’s The Models in its show, despite a court order that had found this masterpiece too fragile to be moved. The art of the Barnes was now capital in the hands of entrepreneurs, and capital entailed risk, even to one of the great paintings (I personally regard it as the greatest) of the 19th century.

The fiasco of exhibiting paintings five miles from their permanent home served an educational purpose of its own, however. It piqued the dormant interest of the local public, as it was intended to; it excited the greed of Philadelphia officials, ever on the lookout for revenues; and it provoked the question of why such treasures should languish behind the gates of the Barnes Foundation when they could give the whole city a badly needed makeover. In short, it set the stage for a bid to pilfer the entire collection from Merion and move it to the Ben Franklin Parkway downtown.

The last 10 years have seen that strategy played out to near-perfection. The prevarication and legal trumpery involved would have shamed most cities, but not Philadelphia.

Richard Glanton, who was forced out as board president in 1997, is on record as opposing a move of the Barnes collection. It was he, however, who made it possible, and he should certainly be willing to take the credit.

The proceeds of the world tour were supposed to pay for renovation of the elegant mansion that housed the Barnes collection. No accounting was given of its disbursement, but large sums seem to have been spent frivolously, and much of the Barnes's financial assets were wasted on suits against the Barnes's neighbors, who, suddenly confronted with the consequences of Glanton’s Barnumesque marketing (noisy bus tours that backed into their driveways, etc.), sought relief to protect their privacy and property. By the time the dust had settled, the foundation was genuinely in debt, with legal judgments hanging over its head.

At this point, Glanton was dismissed, and, seeing opportunity strike, a consortium of Philadelphia-based philanthropies—the Pew Charitable Trusts, and the Annenberg, and Lenfest Foundations—took financial and, finally, executive control of the Barnes.

The last act of the charade was to appear once again in Orphans Court before the ever-obliging Judge Ott, when the Barnes trustees requested permission to move the Barnes collection lock, stock, and barrel to an unascertained location on the Ben Franklin Parkway, there to become part of a new Miracle Mile of the arts. The foundation was so poorly prepared to argue its case that even Ott ordered it to come back with its homework in order. When it did so, it presented not a plan to achieve prudent solvency but one to recklessly expand the scope of its activities in violation of Albert Barnes’s indenture of trust and the law of deviation governing exceptions to it.

Unable to manage its finances at a single location, the foundation now proposed to operate three separate campuses: the first, a new facility downtown to house the collection itself, to be built at a cost of $150 million; the second, a satellite museum of folk art at the Barnes estate of Ker Feal in Chester County; and the third, an administrative center at the Latch’s Lane mansion. The millions of dollars already spent to renovate the latter site would, presumably, be written off.

The hearing revealed that the extent of the Barnes's operating losses had been grossly exaggerated. The Foundation had claimed an annual deficit of $2.5 million, but the auditors, Deloitte and Touche, found it to be only between $1 and $1.2 million. Richard Feigen, the New York art dealer and a former Barnes board member, noted that the Foundation could realize $8.5 million by the sale of a single Courbet not protected by the indenture, and offered to find a puchaser by the end of the day. The Foundation, however, resisted all alternatives to the Pew-designed plan, which included the expansion of its board from five to fifteen members, the additional seats to be filled by Pew nominees, and a state payoff to Lincoln, guaranteed by Governor Rendell and courtesy of the Pennsylvania taxpayer. As one of The Inquirer's own critics commented privately, the Pew Foundation had acquired a $20 billion asset for an outlay of $150 million—a steal, one might add, by any definition of the word.

Judge Ott's decision approving the Pew plan said nothing about the Foundation's dismal record of mismanagement and its trumped-up deficit, and nothing about the law. It simply ratified the heist, while indulging itself in the cynical prediction that the foundation would be back in court again to seek further relief. You can bank on that.

The art world is full of news these days about pilfered treasure. One of the Getty Art Musuem's former curators is on trial. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is being pressured by the Italian government for the return of booty. But the greatest art theft since the end of World War II is taking place right in our fair city. That the loot is moving barely five miles makes it no less a crime—only more of an absurdity.

It is a crime that will produce, in the end, nothing but victims. Lower Merion is losing its crowning glory. Philadelphia's art venues will find themselves beggared as scarce foundation resources are poured into the Barnes boondoggle. The law is already a loser, and so will be art institutions across the country that rely on donors now skeptical of the security of their bequests. The public will lose too, for, as Peter Schjeldahl has written in The New Yorker, the Barnes Foundation has offered not just an aggregate of paintings but a unique and irreplicable aesthetic experience. Even the Pew itself will ultimately lose, its reputation permanently tarnished by a trust-busting power grab.

It doesn't have to be this way. The Barnes can be restored to financial health, its collection retained in the magnificent jewel designed for it, and its educational mission reaffirmed. The resources about to be needlessly squandered can be redirected where they are truly needed in the Philadelphia arts community. The law can be saved from the political and judicial hacks who have flouted it.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller