Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

“The access is the art”

“Access artists” like Alice Sheppard, Natalie de Segonzac, and Carolyn Lazard ignite new languages in dance, theater, and visual art

“The access is the art,” says Alice Sheppard, leaning forward in her custom-built, backless wheelchair, looking simultaneously energized and spent after performing Under Momentum with dance partner Laurel Lawson at Lincoln Center. Her curly, natural hair, normally dyed blonde, has a pink and orange halo. Sheppard is a dancer, choreographer, and founder of Kinetic Light, a disability arts ensemble. She is also one of today’s most eloquent and outspoken champions of a growing movement at the intersection of disability and the arts that (for her and many others) includes gender, queerness, and race.

As Sheppard explains in a March episode of WNYC’s The Takeaway, “My dance is not about overcoming. Disability is at the heart of the creative force—the line, the aesthetic, the movement. The chair is the source. … It’s not adapted from mainstream dance vocabularies. It’s not a sort of deficit translation.”

Defying a deficit mentality

A sea change is underway across the arts, propelled by people with disabilities who—like Sheppard—are defying a deficit mentality and generating new languages in dance, theater, and visual art. Fresh ways of experiencing the arts are also emerging, such as haptic vests that translate music into body vibrations and lyrical audio descriptions of visual media. These constitute emergent art forms in and of themselves, with practitioners using titles such as “access artist.”

One example of this shift is Evidence, now on display at Frenchtown, New Jersey’s ArtYard. It features photography, video, and sculpture by Natalie de Segonzac, who uses a wheelchair. Another, Carolyn Lazard’s non-visual dance installation Long Take, just closed at the Institute for Contemporary Art (here’s the BSR review), though its text is still accessible online to all readers.

At the root of the changes, and what Sheppard, de Segonzac, and Lazard all share, is the conviction that “constraints” can be liberating and expansive. Not only for the artists and their collaborators but for audiences as well.

Fierce forms of freedom

Words like fierce and joyous come to mind when Sheppard and Lawson careen across their ramp-strewn stage in Under Momentum. Like skateboarders on a half-pipe, they use gravity and momentum as key elements of their choreography while still managing to express emotions such as tenderness and playfulness.

“Standard dance is vertical with people moving largely up and down in space,” explains Sheppard at a post-performance Q&A. “Wheelchair dance is horizontal.” However, in Kinetic Light’s Wire, performed at the Shed in New York City last August, they employed circus-like rigging to fly in their chairs, swooping and circling with a verticality that few dancers would dare. (Here’s a captioned, described, and ASL-translated PBS video about Kinetic Light with scenes from Wire.)

Bodies in space

De Segonzac was always interested in bodies in space, her own in particular. Her early photographic work features her naked form alternately embracing and contained by wall-less cubes. She explains the nudity as a way to make the work timeless but also as a form of “hiding in plain sight,” her body more sculptural than anatomical.

In 2016, a dive into the ocean left de Segonzac paralyzed from the neck down at the age of 25. She prefers to call this “my injury” rather than “my accident,” believing it gives her more agency. Years of intense work and rehabilitation have restored significant control of her arms, hands, and legs. A poignant yet humorous video called How to Sit shows her interacting with her wheelchair in every position except the one she was sternly instructed to use. Similarly, Headstand shows the artist standing, facing a corner, back-to-camera, seeming to use her head as a wedge to hold up her body.

De Segonzac felt a powerful urge to make art from her earliest days in the hospital. Balloons 2016 is a stark image of a bundle of dark balloons nearly covering the artist’s body as she lies prostrate in a hospital bed, tubes and wires connecting her to the wall. The balloons were a congratulatory bouquet marking the day she first picked up a blueberry. “I went with [the idea that] the whole world was kind of collapsing in on me,” she remembers, “all this weight, and yet, you know, they're just filled with air. At any moment, they could pop and then I'd be free.”

Whereas Sheppard repudiates anything medical in her choreography (she does not talk publicly about why she uses a wheelchair), de Segonzac embraces the clinical with rebellious flair. The photo Build Myself Thicker Skin is a tightly framed self-portrait in which the artist peers out through a mask woven of heavy wires, plugs dangling like bonnet strings. She explains that these were electrodes used to stimulate her muscles into firing so that she could begin to move them at will. Far from macabre, de Segonzac turns what might evoke pity into profundity.

Three of the show’s most memorable images portray de Segonzac seated in her large electric wheelchair, covered by a huge, white veil that trails behind her like a monarchical train. “Some people see the wheelchair first and that gives them preconceived notions about who I am as a person,” she says. “That veil is just accentuating: ‘Well, if you’re not going to see me, I might as well not show you who I am.’ Perhaps putting the veil on is making myself even bigger and odder.”

Access is art

Driven by its mission to treat accessibility as “an aesthetic of the work and an integral part of the creative process,” Kinetic Light partnered with Lincoln Center to provide 12 forms of experiencing Under Momentum designed for nonvisual, low-sensory, and deaf audiences, in addition to accessible restrooms, routes, and seating. ArtYard reconfigured the building where it houses artists-in-residence to match de Segonzac’s mobility while she worked on its campus, opening the door to future artists.

A new kind of dance film

Lazard, a native Philadelphian, makes art that explores “the relationship between access, aesthetics, and politics.” They cofounded Canaries, “a network of women-identified, femme-presenting, and gender non-conforming people living and working with autoimmune conditions and other chronic illnesses.” Though relatively early in their career, Lazard has had a significant impact on other artists, according to Meg Onli, who curated the show for ICA, which closed earlier this month.

Lazard says they wanted to expand on the 1960s and 1970s movement to democratize dance by making it accessible through film and television: “I wondered what it would be like to make a dance film without images. Art can produce an infinite variety of sensory experiences.” The result is Long Take, which challenges vision as the primary means of perceiving dance. Lazard also strives to make museum-goers active participants in their work rather than a pair of “disembodied, observing eyes.”

In the large, unlit exhibit space, the flooring, engineered for dancers, is noticeably soft. Lazard also added comfortable padding to the standard museum benches in the room. Sounds of movement begin to register in the hushed darkness, seeming to come from everywhere. Three low, black boxes offer digital displays. They are textual “scores” for an invisible dancer.

Lazard refers to Long Take as a “chain of access.” First, they wrote a series of prompts to inspire an improvisation by dancer/choreographer Jerron Herman, also a member of Kinetic Light. Many small microphones attached to Herman’s body captured the sound of his performance—including breath, weight, and percussive use of the floor. This audio mingles with voices reciting the text displayed on the boxes. One voice/text pairing is Lazard reading their prompts, minimalist cues such as “build sequence” or “reverse.” One is a poetic audio description co-written by Lazard and Joselia Rebekah Hughes. This includes phrases such as “tip-toe teeters on the edge” and “disoriented, feet cross, stumble.” The third offers straightforward descriptions of the unseen movements. All three narratives are available in screen-readable text via the exhibition webpage.

Through body sounds, voice, LED text, and ancillary files, Lazard gives people multiple ways to experience dance, noting that “every way of accessing the work is equal and is equally valid.” They want people who encounter Long Take to be “actually transformed in the moment of contact with the work.”

Read part two of this feature: "A responsibility to open the door": How do we embrace disability on an institutional level?

Image descriptions:

At top: Sheppard balances, feet planted, lifting her wheels slightly off the ground as she reaches her arms high overhead. Lawson mirrors her lower embodiment, and leans over, placing her hands on Sheppard's knees and looking up toward Sheppard's raised hands. Lawson is a white dancer with cropped blue hair and Sheppard is a multiracial Black woman with short curly orange hair; they both wear shimmery sleeveless costumes. Text provided by Sheppard. Photo by Christopher Duggan, courtesy of Lincoln Center.

Sheppard performs in Under Momentum: Sheppard zooms up a wooden ramp in her wheelchair, curved arms extended behind her and hair flying. Sheppard is a multiracial Black woman with coffee-colored skin and short curly hair; she wears a shimmery sleeveless costume. Another ramp sits expectantly behind her. Text provided by Sheppard. Photo by Christopher Duggan, courtesy of Lincoln Center.

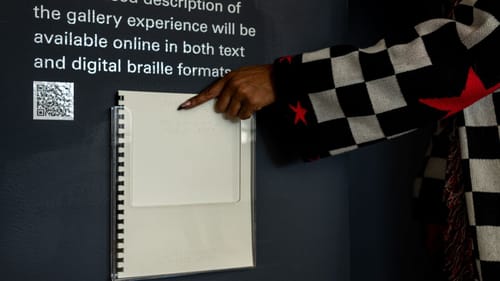

In the gallery of Long Take at the Institute for Contemporary Art: a close-up on the hand and arm of a person with brown skin, wearing a checkered sweater reaching for a Braille print-out of the gallery description. Photo by Constance Mensh.

From the Evidence exhibition: a black-and-white photo of de Segonzac, seen in profile in her wheelchair, with her back to a window and a long, ghostly, elegant white veil draped on her body, with only her lower legs and feet exposed. Gallery photo by Elsa Mora of a photo by de Segonzac.

Editor's note: This link has more information about image descriptions at BSR. BSR provides custom alt text for all images posted on our site and accessibility info for all venues we cover.

What, When, Where

Evidence. Through October 1, 2023, at ArtYard, 13 Front Street, Frenchtown. Free; suggested $5 donation per person. (908) 996-5018 or artyard.org.

Accessibility

ArtYard’s gallery and theater space are wheelchair-accessible via the main river-facing entrance, and all levels are accessible by elevator. Detailed accessibility info is available at artyard.org/plan-your-visit.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Wendy Univer

Wendy Univer