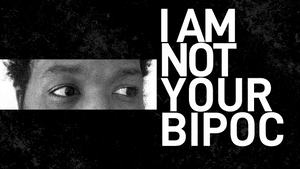

I am not your BIPOC

Why terms like “people of color” are a dangerous de-evolution of language

When I was growing up in a mostly-homogenous Black community in West Philadelphia, I didn’t have much exposure to non-Black people. Outside of a few white teachers at elementary school, the one or two Puerto Ricans in my class, and Ms. Kim—the Asian woman who owned the corner store by my house and would always hook me up with free Lemonheads after school—I had no real sense of what other cultures existed in the world.

As I found myself interacting with more people from other cultures in real life through high school, I discovered swaths of new experiences and perspectives. What I failed to discover, though, was how to properly identify other groups of people. I wondered: How sure was I that Ms. Kim was Korean? Were the two Puerto Rican kids in my class Puerto Rican or was I ignorant of other Latin cultures? Did I ever ask? Did I know to ask?

The voids in my vernacular had become apparent. Having worked in publishing and in journalism for nearly a decade, I see I’m not the only one.

Identity is worth 1000 words

The voids in our language and in how we communicate are evident with terms like “women of color” and “Latinx,” and acronyms like “POC” and “BIPOC.” These have become ubiquitous over the last two years. In the 2010s, “BIPOC” hardly made a blip on Google Trends. Then, the acronym spiked in May 2020 in the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. Prior to that, “POC” was a trend, permeating searches gradually since the early 2000s and seeing similar spikes in 2016 and additionally in the summer of 2020. Both acronyms have declined significantly in searches since then. Search engine trends, however, only illustrate a small piece of what’s really happening and why these terms are not enough.

In their origins, the terms “people of color” and “women of color,” for instance, are not simply descriptors. They carry political, ideological, and historical weight that is often reduced to biological designations. In a video published in 2011, Loretta Ross, an activist and co-founder of reproductive rights organization SisterSong, discussed the origins of the terms “women of color” and “people of color”: in 1977, a group of Black women from Washington, DC brought their own “Black women’s agenda” to the International Women’s Year (IWY) Conference in Houston in response to an inadequate “minority plank” proposed plan of action set by the conference organizers. Other non-Black minoritized women wanted to be included in the agenda, and in those negotiations, the term “women of color” was created.

“It is a solidarity definition,” Ross says, “a commitment to work in collaboration with other oppressed women of color who have been minoritized.” She notes in the end of the video that “people see it as biology now,” and cautions that the reduction from a “political designation to a biological destiny” is “what white supremacy wants you to do.”

American journalism had a moment in 2015, marking “the start of a seemingly endless season of obsessive American political coverage, in the long run-up to the 2016 presidential election,” writes journalist Howard W. French in a 2016 essay. French points out how news organizations substantially underrepresent minoritized people in staff and leadership roles (and are often unapologetic about it), and how topics are type-casted as “Black” or “white” issues. (“Urban affairs,” anyone?) This strips out the nuance of minoritized people’s experiences, as if all Black people and their issues are a monolith.

Words can always hurt me

“This flattening does not necessarily stem from an active desire to do harm,” writes Constance Grady in an essay. “Often, it’s rooted in a desire to be seen as ‘not racist’ or, more broadly, as one of ‘the good guys.’” When terms like “African American,” “minority,” or “diverse” become antiquated, they’re replaced with new terms “without thinking too much about how the new terms are different.” This inaccuracy is harmful, and choosing not to grasp the nuance of these identifying terms is an act of erasure, which ultimately translates as an act of violence.

That violence has penetrated the term “BIPOC” itself when it comes to intercultural relationships. The Model Minority myth has been used to create a racial wedge between Asian Americans and Black Americans, conflating anti-Asian racism with anti-Black racism.

“Racism that Asian Americans have experienced is not what Black people have experienced,” says Claire Jean Kim, a professor at the University of California, Irvine. Amalgamating those varying experiences into one ignores the nuances of a minoritized person’s heritage, culture, and their own lived experiences.

The future of identifying terms

Outside of the Black Women’s Agenda website, there are hardly any records or write-ups about the 1977 agenda and what it brought forth for women of color. Instead, the discourse around IWY is largely centered around white feminist movements and actions, with few articles citing the impact women of color had at what was a culmination of a decade of significant progression for women’s rights. Not surprising—as Ross puts it in the video linked above, “we’re bad at transmitting history.” Think about that: the origins of the term “people of color” yields far fewer results in the same search platform than its contemporary definition, which is becoming increasingly stigmatized because of its ill-informed usage.

Language evolves and sometimes, its history gets lost, but the terms we frequently use to describe non-white people are facing a dangerous de-evolution. “BIPOC” and other terms like “women of color,” “Latinx” and “Latine,” and others have been muddled over the last five years. Without proper context, this de-evolution and misidentification through amalgamation will continue to create rifts, stunt our capacity for understanding the nuances of communities and cultures, and limit the scope of the American narrative.

There are no accurate catch-all terms for any and all groups of minoritized peoples. It’s time we work more diligently to capture the complex illustrations of people and their identities. Otherwise, it’s the evolution of “I don’t see color,” which now exists as “I see one color,” as if BIPOC is a single crayon sequestered into a box all on its own.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Kyle V. Hiller

Kyle V. Hiller