Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Packing up my parents’ house

When home leaves you: a Father’s Day foray into holding on and letting go

According to family legend, my mother refused to unpack for two months.

It was 1965. My parents, along with two-and-a-half-year-old me, decamped from Center City to Wynnewood in pursuit of a scraggle of back yard, a first-floor powder room, and a “good” elementary school just up the street.

But my mother, raised amid the Yiddish-inflected tumult of Strawberry Mansion, feared the suburbs’ quiet and conformity. Would neighbors in flounced aprons come knocking with invitations for bridge and mid-morning coffee? My mother hated coffee; besides, she had no intention of jettisoning her career for the PTA.

My father, a sports writer who’d lived in Brooklyn walk-ups all his life, wanted a home office and room for a couple of tomato plants. So they compromised: an address less than two blocks from the city line, near a bus that could trundle us to Broad Street in 40 minutes.

And there my parents stayed, in the snug brick house, for the next 50 years. They laid wall-to-wall shag carpet, furnished the living room in midcentury modern, re-did the shell-pink kitchen in bold red, white, and black.

Shag and jazz, Davis and tables

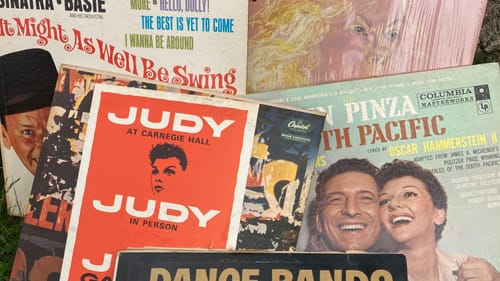

It was the only home I knew, the home where I used to lie on that carpet on Sunday afternoons, listening to the records my dad adored. His tastes were eclectic-jazz, Broadway, solo crooners like Frank Sinatra and Carmen McRae. He taught me to set the stereo’s arm down gently, so the record wouldn’t scratch, how to slide each vinyl disc into the paper vest, then the cardboard jacket.

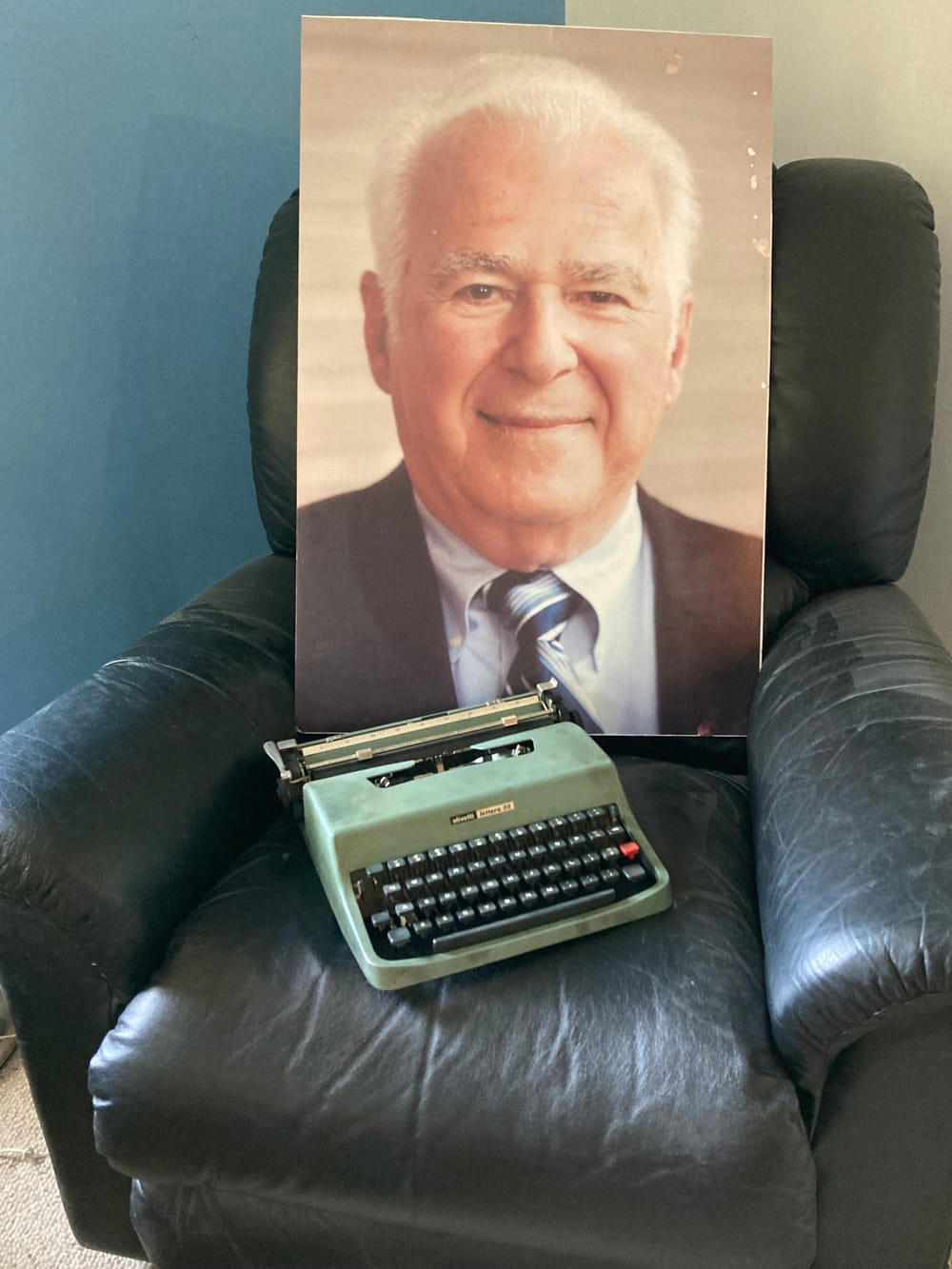

The house’s previous owners had installed an intercom, so you could play a record in the living room and, by flicking some switches, pipe the sound to the kitchen and bedrooms. Miles Davis and Stephen Sondheim lullabied me to sleep, syncopated by the clack of my dad’s Olivetti.

Children live embodied lives; I knew that house the way I knew my hands, my knees, my own untidy hair. I squeezed through the sleek steel bars of the banister to bounce on the couch below; I hid from guests on the sloped pedestal of the dining room table, red tablecloth fringing my lair.

In the basement, I played (ineptly) on the old upright piano, practiced cartwheels (lopsidedly) during a brief gymnastics phase, and had the idea in junior high to turn the place into a French-style bistro, with small tables and wrought-iron chairs (my parents nixed that plan). Later, I made out with boys down there and—much later—with the woman who would become my life partner.

And now—seven years after my father’s death, five years after my mother’s full-circle move back to Center City—we are stripping the house so another family can occupy it.

When home leaves you

It is one thing to leave home. I did that for college, then again, more emphatically, to live in Washington, DC, after I graduated, and finally (with a dramatic chop of those last apron strings) by lighting out for Portland, Oregon, when I was 23.

But it is something else when the house leaves you.

We tackled the closets first: crushed fedoras, mittens long divorced from their mates, so many unworn coats. We stuffed bags and bags for Goodwill. Then my mother’s desk, my partner and I gently teasing her for saving years of day-planners jotted with her impossible script. Dozens of those notepads that come with donation envelopes for worthy causes. A batch of Rolodex cards bearing names and addresses of the dead.

What do we keep? What must we release? What binds us to versions of ourselves that no longer exist? What to do with a half-century’s accumulated stuff?

The file my mother labeled “agonizing letters” from the years after I came out to them? Straight—no pun intended—to the trash. My notes from a college writing class taught by the late John Hersey? Save. A large, rippled negative of my parents’ wedding photo? Nope; we have the color print. But that deckle-edged snap of my dad, age eight, one overall strap falling off his skinny shoulders? Oh, yes.

Pragmatism and joy

For weeks of Sunday afternoons, I was the voice of pragmatism. “Mom, are you ever going to read this/look at this/use this?” I asked again and again. I Marie Kondo’d the mess: keep it only if it brings you joy.

And then, last weekend, I opened a living-room cabinet to find the soundtrack of my father’s life: dozens of cassette tapes, hundreds of CDs, with LPs stacked below. Big Band compilations from the years he and my mom took lessons in foxtrot and swing. Jazz legends: Miles and Thelonious, Stan Getz and Jim Hall. Cast albums from the shows he loved—classics like West Side Story and form-breakers like Rent. The successors to Carmen McRae: Tierney Sutton, Barb Jungr, Norah Jones.

I had to sit down, take a few grounding breaths and touch every CD, as if I could conjure the music—and the man who collected it—with my fingers.

There, now, and then

The February night my father went into the hospital, he had been planning to make dinner for my mother, my partner, our daughter, and me. He’d already been to the farmers’ market for wild salmon and sweet potatoes when he started to feel the nausea that turned out to be pancreatitis.

If that hadn’t happened, we would have walked in the door at 7 to thin-stemmed glasses of a New Zealand sauvignon blanc, the umami smell of soy-ginger-glazed salmon, and a ripple of instrumental jazz.

We’d have sprawled in the living room. There might have been a moment, a caesura in the chatter, when my dad would have paused in the kitchen doorway, right hand oven-gloved, eyes teary with contentment. There: the fire’s fricative pop, the carpet’s gentle itch, a clarinet riff binding me to the “now” even as it passed into “then,” a fragment that will soon slip these walls to live in memory.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman