Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Russian roulette is a dangerous game

The Russian Roulette theory of history

Last April, Dan Rottenberg offered us some thoughts on the causes of World War I, stimulated by a talk by historian Margaret MacMillan. Dr. MacMillan noted that several other crises had ended peaceably and argued that the war might have been avoided “and 17 million lives spared” if some of the minor elements in the crisis had been a little different.

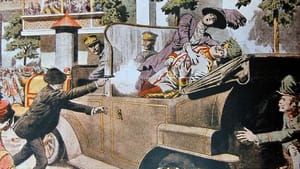

“During the question period,” Dan wrote, “she suggested that, had the Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s chauffeur not taken a wrong turn into a Sarajevo side street in June 1914, thus placing the archduke in the crosshairs of an assassin who had been vacillating up to that moment, World War I might not have occurred at all. . . . For that matter, she added, had Hitler been killed or seriously wounded during the Great War, World War II and the Holocaust might not have happened either.”

What if?

Historians call that kind of speculation “counter-factuals.” Science-fiction writers call it alternate history, and you could fill a couple of dozen bookcases with alternate histories that work out the implications of Lee’s victory at Gettysburg, the Japanese occupation of the western half of the United States, and other possibilities.

My favorite Hitler story centers on a time traveler who offers the Viennese Academy of Fine Arts a substantial gift if they admit young Adolf, instead of rejecting him as they did in our world. Hitler becomes a successful middlebrow artist, with the liberal views artists adapt, but the Nazis rise anyway. Hitler joins the resistance and uses his oratorical powers to broadcast speeches that rally the German opposition during WWII. It’s the only story I know in which Hitler seems likeable. (I haven't managed to locate the title and author of this story, but our indefatigable editor has discovered a variation on this subject that posits a time travelers’ message board.)

I’ve even done a WWI story myself (“The Redemption of August,” in the March 1993 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction). My hero doesn’t try to prevent the war. Instead, he interferes after the armies have started marching and sees that the German war plan — the famous Schlieffen plan — succeeds. He isn’t pro-German or anti-French. He just thinks a German victory is better than the four-year slaughter that followed the failure of the Schlieffen plan.

The Russian Roulette Theory

Margaret MacMillan isn’t the only historian who has looked at the crises that preceded 1914 and wondered why the Archduke’s assassination triggered a catastrophe and the others didn’t. Personally, I think it’s a useless question. I favor a hypothesis I call the Russian Roulette Theory.

If you play Russian roulette with a six-shot revolver, there is one chance in six the gun will fire when you pull the trigger with the muzzle pointed at your temple. Suppose you spin the barrel twice and hear a happy click each time. You go for a third round and — bang!

Why did you come out alive the first two times and die on the third spin? We could analyze things like the force of your spin and demonstrate you would have lived if you had been less energetic. We might even take into account the density of the air and the sweat on your fingers.

But none of that would mean a thing. You died because you were playing Russian roulette.

Loading the pistol

In the years before 1914, the European Great Powers had constructed an international system that included mass armies, rigid mobilization plans, intense national rivalries, and the use of threats and counterthreats. When a crisis arose, there was always a possibility it would end in war.

The factors that could set off the explosion varied from crisis to crisis. In one case, it might be an inexperienced diplomat and a badly translated memorandum. In another it might be a miscalculation by an aggressive national leader. Afterward, you can look back and say the crisis might have ended peacefully if an older diplomat hadn’t been sick or the memorandum had been translated correctly. But things like that always happen sooner or later.

War wasn’t inevitable. A coin can come up heads 100 times in a row. A reckless driver can pass on a hill every month for 50 years and die of old age. The European nations might have survived 50 more crises. But the odds favor shorter runs.

Those who do not remember history . . .

If you really want to travel back in time and change history, I suggest you focus on a factor that influenced every country’s response to every crisis.

In August 1914, it had been 99 years since the last general war among the European powers. The only war between two major powers, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, had supported the delusions of military planners who believed that modern wars would be short and that modern weapons, such as the breech-loading rifle, gave the advantage to the offensive.

Europeans didn’t fear war. In all the major nations, crowds gathered in the streets and cheered when the war broke out. The young poet Rupert Brooke captured the mood with a sonnet that began, “Now God be thanked Who has matched us with His hour.” (One year later, he died of disease en route to Gallipoli.)

What should a time traveler do?

Before you step into your time machine, make an Oscar-quality documentary that portrays the horrors of World War I and explains its consequences. Take it to the leaders of the world and show them what they’re getting into. Rub their faces in Ypres, Verdun, and the Somme. Let the czar know he’s going to be deposed and murdered. Advise Kaiser Wilhelm he will end his life in exile.

Would that have any effect, assuming they believed you? Who knows? You would at least know you had attacked the heart of the problem. If you don’t want people to die playing Russian roulette, get them to stop playing.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Tom Purdom

Tom Purdom