Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Political vampires and poetic transfusions

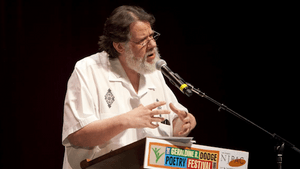

Poet Martín Espada and the 2016 Dodge Poetry Festival

Poet Martín Espada has more than just political and moral differences with Donald Trump. “If what [Trump] is doing is to drain the blood from words, I want to restore the blood to words,” Espada says of the Republican presidential candidate’s rambling, evasive, ill-prepared debate performances and speeches.

I guess Trump can say whatever he wants and then disavow it. It’s as though his former self is some constantly shifting fictionalized “speaker” with no bearing on whatever current phase he’d rather cultivate.

Mixing politics and poetry

But Espada, essayist, editor, professor, Guggenheim fellow, and icon of contemporary American poetry, won’t be a silent observer. He’ll be in the Philadelphia area for the Dodge Poetry Festival, coming to Newark, New Jersey this week. The biennial fest, America’s largest poetry event, is set to draw about 12,000 people to the New Jersey Performing Arts Center and many other stages in Newark’s surrounding arts district.

Speaking with me, Espada says there’s a long history of scholars insisting that poetry and politics don’t mix, but that that philosophy never worked on him or his poems. He’ll appear on a special October 21 panel, “The Work to Be Done: Poetry and Social Justice.” With a title inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’s To the Diaspora, the panel will also include U.S. poet laureate Juan Felipe Herrera; poet, essayist, and columnist Katha Pollit; and bestselling Citizen: An American Lyric author Claudia Rankine.

During the festival, Espada will also read several of his recent works on America’s current turmoil, including "How We Could Have Lived or Died This Way," about the shooting of black people by police.

Owning his words

“Oftentimes in poetry, people talk about the speaker,” Espada says, pointing to the scholarly tradition of separating the voice in the poem from the poet’s own self. He takes a different tack. He doesn’t want to be the hero of his own poems, but he does want to be present in a personal way.

“What I want to do is place myself somewhere in the poem so that you are aware that yes… I bore witness to the suffering, and I speak to you about this suffering… When I’m talking about something I saw or hear, that’s me. Let’s be clear about this.”

But what happens when public figures like Trump hack open an absurd distance between themselves and the things they say? This is what I wondered when Trump dismissed his own comments about his license as a rich, famous man to sexually assault women, and dismissed Clinton's response to him, by saying “It’s just words, folks. It’s just words.

Espada argues, “There’s no such thing as ‘just words.’ In fact, that phrase points up a dilemma in contemporary society that often comes out in political discourse: That we now live in a society where words are increasingly divorced from meaning.”

The danger of euphemism

One example of this trend towards “hyper-euphemism” is use of the phrase “enhanced interrogation” for “torture.”

“Trump represents the worst of that tendency,” Espada continues, because he’s “asserting that words should be empty and often are empty, and he so often uses words without knowing what they mean, or directly contradicting the meaning of something he just said.”

But a bloodless philosophy of words, when speakers try to divorce their words from practical meaning, causes literal blood.

Espada is particularly disturbed by the Boston incident a little over a year ago, in which a pair of white, inebriated brothers who claimed to be inspired by Trump assaulted a Hispanic man. Trump initially denied knowledge of the crime while praising his supporters as “passionate,” as if his racist, xenophobic rhetoric becomes accidentally, blamelessly alive in the hands of his supporters, not in his microphone.

“What he is doing is creating the perception of dangerousness around a particular class of human beings,” Espada says. “The perception of dangerousness is itself dangerous.”

Making the invisible visible

To me, this has never been more evident. In court, police officers are justified in using fatal force not just when subjects possess a deadly weapon, but when officers claim a fear that subjects possess a deadly weapon, whether or not they actually did.

Legally, it’s the perception of dangerousness that matters, not actual danger; the flames of dehumanizing perceptions are increasingly in the hands of citizens like Trump.

“Poetry humanizes,” Espada says, “to make the invisible visible” in writing about the immigrant experience, or any other fraught piece of the American story.

“Your goal is to humanize the dehumanized, and challenge the perception created by Trump and others that these human beings are less than human, and are dangerous.”

During the third presidential debate, millions of us can wonder if we’re tuning in for another 90-minute stretch of “just words.” Meanwhile, several thousand will flock to a four-day festival of words, unparalleled anywhere else in the United States, with a special focus on diverse voices and social justice.

What, When, Where

The Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival. Oct. 20-23, 2016 at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, 1 Center Street, Newark, NJ, and other nearby venues. (888) 466-5722 or dodgepoetry.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Alaina Johns

Alaina Johns