Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Disrupting culture

On violating the "sanctity of the concert hall"

In recent weeks, the Philly Don’t Orchestrate Apartheid campaign, which challenges the Philadelphia Orchestra’s decision to perform during the 70th anniversary of Israel's independence, held multiple actions outside the Kimmel Center. On May 19, 2018, a few protesters entered Verizon Hall at the start of a performance of Tosca.

The Inquirer quotes interim orchestra co-president Matthew Loden telling the audience, “We live in an age where dissent is important. It matters. It should be heard. But the sanctity of the concert hall should be respected.”

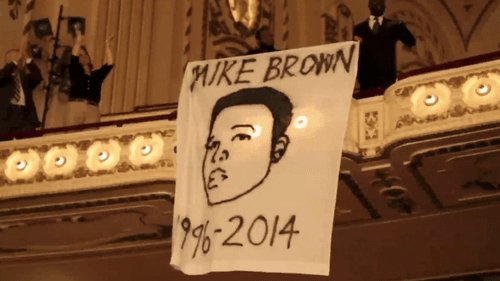

In response, one commenter on social media wrote, “Very happy to hear that they disrupted the performance. Screw the 'sanctity' of the concert hall. Stop entertaining the ruling class, making contributions more important than human lives.” In 2014, Black Lives Matter protesters disrupted the Saint Louis Symphony, albeit during intermission. Though it was a comparatively small protest within the movement, the disruption received substantial media attention.

No safe spaces in art

The concern that classical music primarily serves the elite is legitimate. Musicologist Marianna Ritchey observes that classical music is used in contemporary society to index universal good virtue and high ideals, making it susceptible to use by powerful institutions — often corporations — to paint a positive image for themselves. Western art is seen as both neutral/universal and virtuous, hence its value to the “cultural diplomacy” for which the Philadelphia Orchestra has become known.

When I attended a Philly Don’t Orchestrate Apartheid rally a few weeks ago, many of the protesters were not anti-orchestra but in fact classical music fans, many Jewish (like me). These participants saw the orchestra’s performances in Israel as a chance to speak out about human rights and police brutality.

With some exceptions, most participants had zero interest in preventing the audience from enjoying the performance. The audience reception was generally hostile; one concertgoer slammed the door violently against a protester’s dog.

Loden’s comment about the “sanctity of the concert hall” recalls President Trump's tweet that theater should be a “safe space”; this was in response to a Broadway performance of Hamilton that called attention to Vice President Mike Pence, who was in the audience. Loden was rightly challenged by Phil Gentry in a recent Inquirer commentary.

As Gentry notes, the action at a performance of Tosca is especially fitting. There is a particularly rich history of political messaging in opera, most often communicated through allegory. Our cultural institutions are certainly aware that art and protest, including classical music, can go hand in hand.

Disruption works

In 2013, Opera Philadelphia staged a production of Verdi’s Nabucco that attempted to convey the opera’s social meaning when it was first performed, complete with a showdown between protesting musicians and armed guards.

The 2014 Black Lives Matter and 2018 Philly Don’t Orchestrate Apartheid protests show that disruptions of symphonic concerts, even when carried out by only a few people, can help communicate a message.

Certainly, not all disruption is good disruption. I see the orchestra’s appearance in Israel as a great opportunity for activists to raise concern over Israel's occupation and human rights violations. I agree with the sentiment that an international trip by an orchestra is never politically neutral. I also agree with Jewish Voice for Peace member Marta Guttenberg, whose letter to the Inquirer (which appeared only in the paper's print edition) noted that the argument that the trip is for “cultural diplomacy” is disingenuous, since there is no conflict between the United States and Israel.

Years ago, another organization considered an action at the annual Opera on the Mall event. We hoped its sponsor — PNC Bank — would stop investing in mountaintop-removal coal mining. I called Opera Philadelphia’s development office to figure out whether PNC executives would be attending.

It was an uncomfortable phone call, during which I emphasized that we were not considering anything that would prevent the audience from enjoying the concert. The opera employee explained they were not endorsing mountaintop removal but, rather, that they would take money from anyone.

Public money for the arts instead of war could be good framing for future actions. The stance of taking money from anyone is entirely understandable, but it does not make the opera neutral or immune from consequences if that money comes at the expense of community health and safety.

We decided against holding an action at the opera, though we did hold demonstrations outside a few PNC-sponsored FringeArts events. Our campaign targeting PNC was ultimately a success. We are now targeting PECO to do significantly more to develop renewable energy and jobs in underinvested local communities.

I believe classical music is still valuable and can do good. It can make us think. It can draw attention to an ongoing social movement or campaign. It can even use its ability to attract money and power to fundraise for good, as with the recent Symphony for a Broken Orchestra. But yes, in the words of the Philly Don’t Orchestrate Apartheid commenter: “Screw the sanctity of the concert hall.”

To read Robert Zaller's essay about the Philadelphia Orchestra's tour of Europe and Israel, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Benjamin Safran

Benjamin Safran