Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

New directions

On maps, GPS, and the value of getting lost

My daughter doesn’t mind that her mother has gray hair. She isn’t embarrassed by the fans of creases at the corners of my eyes.

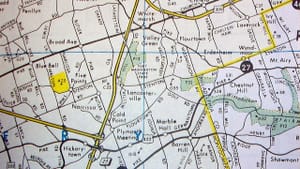

It’s my map books she can’t tolerate — the torn-up, spine-bent, coffee-splashed atlases of New Jersey and southeastern Pennsylvania that I insist on keeping in the passenger seat pocket of my Honda Fit. The maps that, in this era of GPS technology, mark me indelibly as “old.”

We fought about the maps again last week, when we set out for a bicycle shop in Northeast Philly, a drive I vaguely remembered from our last bike purchase a few years back. Somehow we veered off Welsh Road and ended up in the 9600 block of Roosevelt Boulevard instead of the 9200 block, requiring a hairpin 180-degree reversal and a four-lane cross-over before we finally found the store.

During our brief detour — Elissa was driving, and I was riding shotgun — I reached behind the seat for my Philly road atlas. “Oh, God!” Sasha groaned. “Why didn’t you just tell me to use my phone? We’d have been there 20 minutes ago. You. Always. Do. This!”

She’s right on that one. I’ve been doing this for more than 50 years.

Another roadside distraction

My family has a trove of stories chronicling our roadside distractions. Once, after visiting me at college in New Haven, my mother zipped onto I-95, but — whoops — headed north instead of south. She didn’t notice the mistake until she spotted signs for Providence, Rhode Island.

Another time, on a family trip to Washington, D.C., we rode the Beltway like a Mobius strip, circling round and round the capitol until we finally gave up on seeing the Lincoln Memorial and went to Baltimore instead.

And every Passover, we got completely bollixed on the 12-mile journey to my cousins’ house in Cheltenham. There we were, on our way to tell the story of our ancestors’ flight from Egypt, making our own long and winding exodus from Wynnewood.

It was a ritual: directions jotted on a scrap of newspaper in my mother’s inscrutable handwriting; grumpy exchange in the front seat as my dad muttered, “I thought you knew where to turn,” and my mother replied, “Well, I thought so, too.”

There were no cell phones, of course, and nary a gas station in the residential cul-de-sacs, so we drove and drove, checking street signs and backing out of strangers’ driveways, until we happened upon Brookfield Road, almost by accident.

I loved it. A low-stakes squabble between my usually peaceable parents, a scenic tour of East Oak Lane and the near Northeast, the thrill of temporary dislocation. We weren’t desperately adrift — nothing like our Israelite forebears with their 40 years of kvetchy wandering — just a little out of our way. “Are we lost?” I’d ask gleefully from the backseat. “I hope we’re lost!”

What happens to serendipity?

But my teen has no tolerance for such waywardness. With her iPhone delivering precise guidance (“in one-third of a mile, make a soft left onto Huntington Pike”), there’s no room for instinct, hesitation, or error. No need to stop and ask directions from the extravagantly tattooed clerk at the 7-11, or even to pull to the shoulder and check grid 3318 of the trusty, tattered map book.

What happens, I wonder, to serendipity, to discovery, to taking a wrong turn on the way to a Cherry Hill roller rink one winter afternoon and ending up on a block wild with Christmas kitsch, every lawn so jammed with reindeer, Santas, and elves that we had to stop and take pictures?

If you navigate life by GPS, what happens to the ability to find your way by intuition and memory, by landmarks that, over time, acquire totemic significance? When I was young, I knew we were close to my grandparents’ house when we passed the billboard I dubbed “The Man Who Always Eats.” I still give directions that way, as if I lived in rural Kansas: Turn left at the boarded-up drugstore; drive past the yellow house with the fading shingles.

Being embedded in the world

There is an aboriginal tribe in Australia whose language has no words for egocentric directions. No “next to me” or “on your right.” Instead, they might say, “Could you move a bit to the east?” or “Look out for that biting ant north of your foot!” I imagine a conversation between my daughter and a member of this tribe: “Hey, where’s your GPS?” she asks. And the Australian aborigine answers, “It’s in my southern pocket.”

This tribe’s linguistic habit must foster a different sense of being — more intimately embedded in the world, tethered by a common web of compass points.

I can’t imagine it. There are days I feel sadly disconnected from my surroundings, like a child spun blindfolded in a game. Which way to turn? Where the hell am I going? It’s why I cling to those map books, whose tidy grids remind me how this road leads to that one, how my little corner is connected to everything else.

O tempora! O mores!

Maybe my daughter’s right. I am old. I pay my mortgage with a check, use a landline, and feel loath to outsource my brain to a device the size of a graham cracker. I know, I know: Every new efficiency triggers a generational lament. I’m sure people fretted that printed books would stunt our memories, that the typewriter would make handwriting obsolete. And look what happened: Time and even newer technologies proved them right. My grandmother, with her eighth-grade education, could recite skeins of Shakespeare; now, why learn sonnets by heart when you can fetch one in a couple of clicks?

My family never did grasp the quickest route to Brookfield Road. But I learned other things along the way: that we were fallible. That we could laugh, even when we were hopelessly lost and embarrassingly late. That the shortest distance from point A to point B wasn’t always the richest ride.

It was good practice for the rest of my life — for sudden turns and surprising detours, for a route laid by instinct and guesswork. I wish nothing less for my daughter. I hope, from time to time, she will find herself lost — good and lost, and without a GPS — so she, too, can know the dizzied sensation, the circuitous journey, the sweet stumble that will finally bring her home.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman