Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

To 'scape the serpent's tongue

Difficult plays and the critics who love them

Last week I took my Villanova University students to see Christopher Chen’s world-premiere drama Passage at the Wilma Theater. The play’s title comes from E.M. Forster's novel A Passage to India, and the script is inspired by the novel but is utterly its own creation. It was difficult. It was visually stunning. It made me uncomfortable and angry. It was hard to understand at times. The ending pushed me away and then grabbed me by the collar and drew me in. I loved it because it was all of these things.

If you wanted comfort and ease, this was not that play. This play challenged me in ways I didn't expect. This is why I come to the theater.

I have a longtime, ongoing artistic relationship with the Wilma, which will produce the Philadelphia premiere of my play Kill Move Paradise in the 2018-19 season. The Wilma has been a place of great artistic risk and reward for me. This naturally colors how I see them and their work.

With all that out of the way, I'm mad confused by dismissals of this production by this city’s critics. This is partly because I love the Wilma, but it's also because these kinds of reviews create a hierarchy around what is acceptable (read: beautiful, appealing, worthy of viewing) theater.

Work harder

We live in an on-demand era that allows us to switch on Netflix any time and stay home. I’m guilty of it; TV is in a golden age.

But what theater offers is something you have to see live and with other people. If critical acclaim is only given to easy, recognizable plays, this teaches that theater’s function is to churn out art that is a live-action version of something we could stay at home and watch. Why get dressed, get a sitter, drive/bike/train/walk to the theater?

I have huge respect for critics' work. Reviewers should be critical of what they see onstage and it’s important for those criticisms to be published as a record of the work a community creates.

However, I don't think it’s a critic’s responsibility to dismiss the theater a community makes, and I have seen this happen time and again to plays, to performers, to whole theater companies — not because the play was wildly offensive or deeply problematic, but because it didn’t fit a form that was pleasing to the reviewer.

I'm a theater artist. I've received bad reviews. I don't mind someone saying "Ijames's performance lacked energy" or "The end of Ijames's play seemed abrupt."

Failure is part of art-making. It's what makes art forms grow. But if you can't take a risk on anything for fear a mean-spirited review will tank your ticket sales or end the life of your play (or even your career), what is the ultimate good that comes from a review?

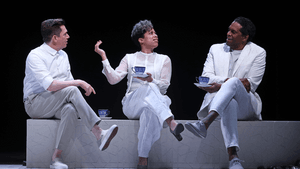

{photo_2}

Work smarter

Saying, as one critic did, that "E.M. Forster is rolling in his grave" does not address the merits or flaws of the play, borders on elitism, and is presumptuous as fuck.

To that, I say, a.) How you know? b.) So what? c.) If my play can make the dead move, I'm doing something right.

The whole point of that critic’s review was the ways the play differed from Forster’s novel. But what does that have to do with what happened in the theater the night the critic saw the show? I’ve never read A Passage to India. Does that mean my experience of the play was somehow incomplete?

Another passage from that same review was particularly confusing to me: "Blanka Zizka directs the Hothouse ensemble to speak loudly and distinctly, resulting in unnatural, exaggerated dialogue, and often inviting the audience to laugh and clap approvingly."

Imagine that, an audience having a good time. J’accuse! Also "unnatural, exaggerated dialogue"? You mean, like this?

Another critic said, “Christopher Chen’s play — with more themes than a Disney Park but primarily about being an oppressor vs. being oppressed — begins with a credible plot and turns abruptly toward the end into something resembling a sermon. It feels like we accidentally hit the remote.”

My problem with this review is that it doesn’t meet the play where it is but chastises it for not behaving in a “credible” manner. What does that mean? It also assumes the playwright made some kind of mistake.

It’s one thing to say “I didn’t like the ending.” It’s another thing to say “The ending fails because it doesn’t follow the logic the playwright initially presented to me.” That’s the writer’s choice.

Pay attention

Playwrights who use structure to disrupt an audience’s understanding are intentional about this. When I see a play that throws me I don’t assume the play is bad, I assume the play is asking for me to be thrown.

Again, this is not about critics disliking the play. It’s about critics writing about a play as if it is a child throwing a public temper tantrum.

This same critic says that “the last minutes of Passage… had a jarring final scene that forced us to figure out whether we were watching characters or the actors playing them.… A character comes out to talk to us directly, and with a lot of what-ifs about the play. I assume Chen’s addendum prods us to think about what we’ve just seen, but isn’t his play supposed to do that?”

The critic calls the ending an “addendum” as if it isn’t part of the play. It is the play. It’s placed where it is because the playwright wants to give the audience a particular experience. This is like saying Puck’s final monologue at the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is an addendum.

“Isn’t his play supposed to do that?” Well, friend, it is, in fact, doing it, because the play’s not over.

Look around

This critic treats the play’s final moments as if it were a post-show discussion and not connected to the larger story. I guess I’m asking if it’s possible to encounter something you may feel doesn’t make sense and discover the ways in which it makes complete sense?

That’s hard work and requires an extension of the theatrical imagination. I mean, let’s talk about all the sleeping potions, mistaken identities, and deus ex machinae in Western theater. We accept them because we choose to believe.

Disregard of art that requires work to understand will be the death of the theater. It’s probably really Pollyanna-ish of me, but I believe critics, art, and artists live in a super-symbiotic ecosystem.

How can critics and artists make sure people are inspired to keep filling the seats? Theater offers the opportunity to create new kinds of logic, to create worlds, to rearrange perceptions in ways TV and film cannot. This means playwrights writing plays that disturb what we consider normal, acting that may feel unrealistic, adventurous direction, and startling design. How can we work together to make the “familiar strange and the strange familiar”? (That’s not mine; it’s Novalis's, but it’s cute, right?)

I want critics to do what they do best: critique — offer a detailed analysis and assessment.

Philly is filled with people making difficult and sometimes confusing theater. This isn’t a bad thing. It is theater that actually reflects the times we live in. Difficult and confusing is how it feels to be alive right now.

To read Mark Cofta's review of Passage, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

James Ijames

James Ijames