Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Always be closing (your mouth)

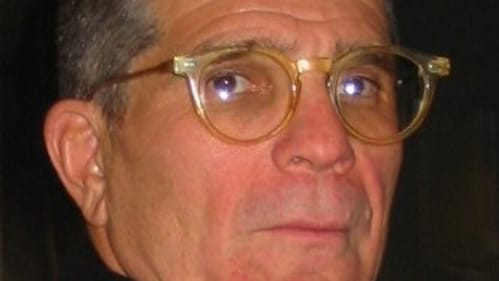

David Mamet's talkback tantrum

Just like your uncle who wore his “Make America Great Again” cap to Thanksgiving dinner, David Mamet has become something he never was before: relevant. Balling up his little fists, he placed them on his hips, declaring ‘no talkbacks” after Oleanna. No backsies, folks. Mamet gives and you take. I mean talk. I mean, don’t talk.

Yakety yak

A talkback, of course, is a ritualized punishment in which audience members are held captive in a theater after the production ends. They are then forced to listen to the tenuously content-related personal experiences and grievances of people who like to hear their own voices and seek a captive audience.

You’ll never catch me advocating for talkbacks. All kinds of discourse in our country proceeds on the premise that if we engage in rational discussion of important issues, the best ideas will find their way to the top. The truth is that even with a masterful facilitator, it is almost impossible to hold a conversation of any value with 50 or more people who are all facing the same direction. It is in all ways impossible to hold a conversation that gives each of those voices weight. No moderation strategy will make a contemplative introvert enter the arena with a blowhard, or the victim of rape or racism reopen barely healed wounds and defend herself to a skeptic. Any meeting, classroom discussion, or dinner party will eventually be taken over by those with the least investment in the issue at hand.

In my life of dramaturgy, I have moderated dozens of talkbacks, most dominated by white men who may never have imagined it possible for them to be wrong or boring. Talkbacks have given me the opportunity to hear white men hold forth on such topics as: what Afghan people really want, how black people really talk, what being a mother who has lost a child actually feels like, and when rape is funny. Unlike Afghans, black people, mothers, and survivors who remain silent, it cost these men nothing to speak. There was no danger they’d be told they didn’t understand their own experience or have their humanity put up for debate.

Don't talk back

Researcher Janet Holmes showed in a 1999 study that when men judge the proportional contributions of women in a group discussion, “the talkativeness of women has been gauged in comparison not with men but with silence. Women have not been judged on the grounds of whether they talk more than men, but of whether they talk more than silent women.” As a result, when those men walked out of my talkbacks, they felt they had participated in open discourse, with no hint they’d actually stifled it.

If you spend your life that way, as David Mamet (who has a brilliant ear for dialogue but is tone deaf to the human experience) has, you also believe you are participating in a larger, inherently fair, democratic conversation in which your success represents nothing more than your rightness. This is why there is a certain type of white man who believes that disagreeing with him equals censoring him. The speech of others multiplies in his mind against the standard of an unconsciously expected silence, a silence he registers as equal participation.

Mamet complains in Writing in Restaurants, “We live in oppressive times. We have, as a nation, become our own thought police; but instead of calling the process by which we limit our expression of dissent and wonder ‘censorship,’ we call it 'concern for commercial viability.'” Or we call it “contractual obligation,” I guess. And this is why he’s — sadly — relevant. Mamet just says what so many of his political fellows say: talking back is talking too much.

The same people who spent an irritating decade making the case that true free speech and equality meant being allowed to use racial slurs now get hurt feelings when they are merely identified as straight white men. Why do we bring race, gender, queerness, or disability into it? Why do we make noise where there used to be a comforting silence?

Structural perversity in Shanghai

That’s Oleanna (which last appeared on an area stage during Bristol Riverside Theatre's 2012 season and, before that, in 2010 at Curio Theatre Company) in a nutshell. A man and woman walk into an office on equal terms. She creates the perception of inequality to tip the balance of sympathy, and therefore power, in her favor. It makes perfect sense that the same man who thinks he’s a hero for exposing the dark truth about the power women wield by accusing men of rape also believes disagreeing with his worldview victimizes him. This is the Escher-esque world of “political correctness,” where defending yourself means censoring your attacker and attacking means defending yourself against the victim.

I saw a production of Oleanna in Shanghai in 2011. The final line of the play comes when (spoiler alert) the poor male professor can’t take the clamor anymore and punches his female student. (When Mamet says he doesn’t want “the impact of his play to be emotionally truncated by a structured discussion,” I assume he means the impact of this powerful lesson: Sometimes bitches ask for it.)

In the original English, the student responds to the blow, saying “That’s right, that’s right.” Meaning, “See, I knew you were evil, I just had to push you hard enough.” Something happened in the translation though, and the Chinese production ended with the student saying, “That’s your right.” Which is much more to the point. Our silence has always been your right. To perceive our silence as our having an equal voice has always been your right. To pop us one when we talk back, to lynch the uppity, has been and in many ways still is your right.

Mamet’s plays are his intellectual property. He can tell everyone to shut up and listen if he wants; that’s his right, too, even if that makes him a hypocritical baby. When it comes to talkbacks after Oleanna, I don’t want them either, because there is no good Oleanna talkback. If we have to endure productions of Oleanna for some reason, I’d rather suspend my disbelief and imagine that this kind of myopia is specific to its author. If theaters insist on dragging audiences through Mamet’s Alice in Wonderland reality, where refusing to be overpowered is violence against the powerful, then good Lord, don’t make us live that reality out in the aftermath. It’s bad enough Mamet said it; let’s not sit among our fellows and entertain it.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Cara Blouin

Cara Blouin

Illustration by Hannah Kaplan

Illustration by Hannah Kaplan