Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

To an athlete who couldn't let go

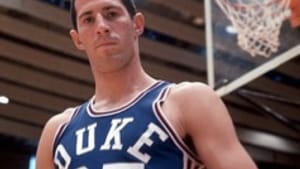

Art Heyman: Athlete stuck in time

Art Heyman, who died last week in Florida at 71, with no known surviving kin except a former wife, was perhaps the most forgotten and downgraded truly great college basketball player of the modern era.

The reason that it's so startling to recall his greatness at Duke is his disappointingly abbreviated professional career. Although Heyman averaged 15.4 points as a New York Knicks rookie guard in 1963-64, and had several good years in the American Basketball Association, including winning a championship, his pro career was over in just six years, only three of which were productive.

That era of the birth pangs of professional basketball was full of transgressions and transgressors: Spencer Haywood, Connie Hawkins, Jack Molinas, Chet Forte; scandals, false accusations, lawsuits, addictions, all in the wake of a professional league struggling for legitimacy after having been a dance-hall second attraction.

The four-year rule

Heyman's diminished legacy is a victim of the prevalent practice of judging players solely on the basis of their success in the NBA. This is an understandable standard today, but at that time players routinely stayed in school because (before Spencer Haywood successfully challenged the practice with a lawsuit), players who began college could not turn pro until their class had graduated.

And so there was world enough and time for players to have real college careers. Heyman was a spectacular college player, but not well suited for the pro game that rigorously demanded more speed.

Bill Bradley is another example: Although he thrived as a vital cog in the offense of a Knickerbocker team that had been radically remade shortly after Heyman's stint by the transformative advent of Willis Reed, Walt Frazier, Dick Barnett, Dave DeBusschere and Earl Monroe and Bill Bradley. Bradley's self-effacing pro game gave no clue as to his greatness and ability to dominate games in college, where he turned Princeton into a national championship contender.

A queen on the chessboard

At Duke, the powerful six-foot-five-inch Heyman was dominant. Like a queen on the chessboard: he could do so many things at so many positions— kind of like Lebron James, except in two dimensions. But then the game was largely played in two dimensions; only centers"“ and Elgin Baylor— played above the rim.

Another reason for Heyman's faded fame was that he had a deserved reputation for being a hothead, even a head case. Where Bradley became a U.S. Senator and nearly the Democratic presidential nominee, Heyman's obituary in the New York Times emphasized the fights he used to have with Larry Brown, with whom he grew up on Long Island, but said nothing of substance about his life after basketball.

Heyman and Brown were rivals in high school, college and the NBA, but Brown grew up. Heyman remained stuck in time. No cause of death was reported. Mention of his post-basketball life was limited to his having named a bar he once owned and named for his ex-wife's daughter, Tracy. The thought of suicide had to cross a knowledgeable reader's mind.

Playground conversation

About twenty years ago, my father was watching a playground game in New York through a fence when, somehow, he found himself talking to a 50-ish six-foot-five-inch, athletic-looking white guy who eagerly introduced himself as Art Heyman, and proceeded to regale my dad with stories about his exploits in the 1964 Olympics.

Having graduated from college myself in 1964, and having attended the Olympic basketball trials that year at St. John's University, I was dumbfounded at the preposterousness of this bogus claim: Heyman had graduated in 1963, after leading Duke to a semi-final berth in the NCAA for the first time.

Had 1963 been an Olympic year, Heyman surely would have represented the USA; but a year later, he no longer had the "amateur status" that was then required to compete in the Olympics. This was merely the luck of the draw, much like the Selective Service lottery that was instituted several years later.

Basketball heaven

Such a self-promotional story could be dismissed as garden-variety bragging in order to show oneself in a better light than as a failure, but it was not as if Heyman had dropped off the basketball map before the Olympics and become a working stiff in some lousy office job. No, he was playing in the NBA; Madison Square Garden was his home court; he was named to the NBA all-rookie team.

A friend of mine conceives of heaven as a place where the all-time greats gather, each in the prime of his career, for the purpose of allowing us fans to settle our fruitless arguments as to how players of different eras would have fared in head-to-head competition. I imagine Heyman on the sidelines, pleading his own case for inclusion, plaintively shouting "Next" to deaf ears.

Too bad. This guy could really play.♦

To read responses, click here and here.

The reason that it's so startling to recall his greatness at Duke is his disappointingly abbreviated professional career. Although Heyman averaged 15.4 points as a New York Knicks rookie guard in 1963-64, and had several good years in the American Basketball Association, including winning a championship, his pro career was over in just six years, only three of which were productive.

That era of the birth pangs of professional basketball was full of transgressions and transgressors: Spencer Haywood, Connie Hawkins, Jack Molinas, Chet Forte; scandals, false accusations, lawsuits, addictions, all in the wake of a professional league struggling for legitimacy after having been a dance-hall second attraction.

The four-year rule

Heyman's diminished legacy is a victim of the prevalent practice of judging players solely on the basis of their success in the NBA. This is an understandable standard today, but at that time players routinely stayed in school because (before Spencer Haywood successfully challenged the practice with a lawsuit), players who began college could not turn pro until their class had graduated.

And so there was world enough and time for players to have real college careers. Heyman was a spectacular college player, but not well suited for the pro game that rigorously demanded more speed.

Bill Bradley is another example: Although he thrived as a vital cog in the offense of a Knickerbocker team that had been radically remade shortly after Heyman's stint by the transformative advent of Willis Reed, Walt Frazier, Dick Barnett, Dave DeBusschere and Earl Monroe and Bill Bradley. Bradley's self-effacing pro game gave no clue as to his greatness and ability to dominate games in college, where he turned Princeton into a national championship contender.

A queen on the chessboard

At Duke, the powerful six-foot-five-inch Heyman was dominant. Like a queen on the chessboard: he could do so many things at so many positions— kind of like Lebron James, except in two dimensions. But then the game was largely played in two dimensions; only centers"“ and Elgin Baylor— played above the rim.

Another reason for Heyman's faded fame was that he had a deserved reputation for being a hothead, even a head case. Where Bradley became a U.S. Senator and nearly the Democratic presidential nominee, Heyman's obituary in the New York Times emphasized the fights he used to have with Larry Brown, with whom he grew up on Long Island, but said nothing of substance about his life after basketball.

Heyman and Brown were rivals in high school, college and the NBA, but Brown grew up. Heyman remained stuck in time. No cause of death was reported. Mention of his post-basketball life was limited to his having named a bar he once owned and named for his ex-wife's daughter, Tracy. The thought of suicide had to cross a knowledgeable reader's mind.

Playground conversation

About twenty years ago, my father was watching a playground game in New York through a fence when, somehow, he found himself talking to a 50-ish six-foot-five-inch, athletic-looking white guy who eagerly introduced himself as Art Heyman, and proceeded to regale my dad with stories about his exploits in the 1964 Olympics.

Having graduated from college myself in 1964, and having attended the Olympic basketball trials that year at St. John's University, I was dumbfounded at the preposterousness of this bogus claim: Heyman had graduated in 1963, after leading Duke to a semi-final berth in the NCAA for the first time.

Had 1963 been an Olympic year, Heyman surely would have represented the USA; but a year later, he no longer had the "amateur status" that was then required to compete in the Olympics. This was merely the luck of the draw, much like the Selective Service lottery that was instituted several years later.

Basketball heaven

Such a self-promotional story could be dismissed as garden-variety bragging in order to show oneself in a better light than as a failure, but it was not as if Heyman had dropped off the basketball map before the Olympics and become a working stiff in some lousy office job. No, he was playing in the NBA; Madison Square Garden was his home court; he was named to the NBA all-rookie team.

A friend of mine conceives of heaven as a place where the all-time greats gather, each in the prime of his career, for the purpose of allowing us fans to settle our fruitless arguments as to how players of different eras would have fared in head-to-head competition. I imagine Heyman on the sidelines, pleading his own case for inclusion, plaintively shouting "Next" to deaf ears.

Too bad. This guy could really play.♦

To read responses, click here and here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.