Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Lift every voice

Adventures in cultural appropriation

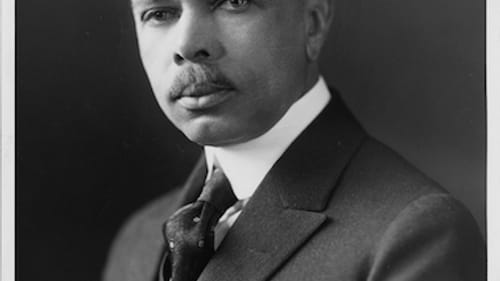

It was 2015 and I was staring up at another deadline. The art-song group Lyric Fest, with whom I was enjoying a season as their first resident composer, asked me to write a work for a concert with the Singing City choir called “I’ll Make Me a World.” That’s a line from “The Creation,” James Weldon Johnson’s imaginative reworking of the Bible's Book of Genesis.

I suggested setting some of Psalm 19, the great response to creation. Haydn and Beethoven, their music large and loud, found their way into texts based on that psalm, translated as “The heavens are telling.” That’s what I wanted: large, loud, and, from the Renaissance I had been rediscovering for the past decade, polyphonic. Independent voice against voice. That’s what I was looking for.

Then I read “The Creation”:

And God stepped out on space,

And he looked around and said:

I’m lonely —

I’ll make me a world...

That stopped me. I already knew Johnson’s hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” called the “Black National Anthem” by the NAACP (Johnson, in his multifaceted career, led that organization in the 1920s). Associated with the Harlem Renaissance, he led me to other writers. This, from Langston Hughes, caught my eye:

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune,

Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon,

I heard a Negro play.

Down on Lenox Avenue the other night

By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light

He did a lazy sway...

He did a lazy sway...

To the tune o’ those Weary Blues.

Something was hunting me; I couldn’t place what. The deadline was looming, I was far from Psalm 19, and composers know this desperation, when their eyes narrow as wolves’. I thought of Down from the Mountain, the documentary of the music and performers in the film O Brother, Where Art Thou? It includes a male gospel group, the Fairfield Four, singing "Po Lazarus." While they wring out the single, leathery, winding chant, they set the time, and it’s slow: Stomp (and wait). Slap (and wait). Stomp (and wait). Slap (and wait).

It’s a patient time, alarmingly so, a time slogged in fields and forged in chains. It’s a time with eyes that see all the way to the horizon and beyond. My unwritten piece was becoming different, and Johnson, Hughes, and the Fairfield Four were showing me how.

I asked myself if this was cultural appropriation. I thought of Brahms’s Hungarian dances, of Paul Simon’s South African and Cajun songs. If it sounds Hungarian or South African, fine; if it doesn’t— well, also fine? It only matters if the music’s good, I answered myself. Culture can be identified, but can it be owned? If nobody owns it, can it be stolen?

Black and white Americans collected African-American folk music even before Vaughan Williams and Bartók collected theirs. Among others, African-American composers William Dawson, Hall Johnson, Jester Hairston, and the great Harry T. Burleigh arranged and sung them.

Choirs of all races performed them, complete with Southern patois. Hairston couldn’t sing in Johnson’s choir until he shed his Boston accent. Johnson told him, “We’re singing ain’t and cain’t and you’re singing shahn’t and cahn’t and they don’t mix in a spiritual.”

Culture is never monolithic. Most Germans wouldn’t be caught dead in lederhosen. A black singer friend left her mostly black church because she was told the spirituals she wanted to sing were “slave songs”; they wanted gospel music.

This argument — folk music versus oppression’s legacy — goes back to the Civil War. Later, the Harlem Renaissance urged a return to primitivism, away from European-sounding music. Other African Americans, though, showed they could compose “Western” classical music just like anyone else.

I cannot know what it’s like to be black, let alone a slave or descendant of slaves, but I can respect and take my time. Art takes time, just like good manners. Invited to dinner, I don’t push past the host to the table. We enjoy each other’s company and dinner’s included.

The guest should be understanding, but so should the host. Cultures host. Everybody’s Irish on St. Patrick’s Day, we joke, and there’s something to learn, even from a saint’s day stretched beyond recognition. A culture lives through its people, but people don’t live through their cultures. People live through other people.

James Weldon Johnson and Langston Hughes and the Fairfield Four found me and invited me in. What was I to make of this world?

The heavens declare the glory of God, the skies announce the work of his hands.

Day after day they pour out their speech, night after night they tell what they know.

I stomped and waited. Then, into me, the music perceptibly swayed. Down from Haydn’s large and loud mountain and heavens it now found me and slowed me down to a mellow croon. From voice against voice, I heard one voice. From my Renaissance polyphony I saw all the way to the Harlem Renaissance, and past, to a spiritual, a single chant. (See Lyric Fest/Singing City’s performance here.)

The Heavens Declare doesn’t sound like a spiritual, but I don’t mind saying that it comes from them. If it comes from my heart and goes into other hearts, if we hear it, together, it will not be appropriation.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Kile Smith

Kile Smith

Illustration by Hannah Kaplan

Illustration by Hannah Kaplan