Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Part one: The power of space

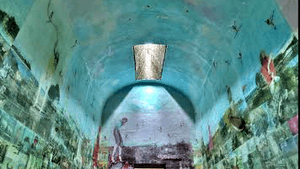

2016-2017 Artist installations at Eastern State Penitentiary

Describing the ontological dimension of space, I sensed the prison’s warden was not getting my point or, perhaps, not buying it. Pushing, I explained prison defined him as having certain powers but, I continued, when he left prison and his wife wanted the garbage taken out, these parameters no longer existed. Prison defined him as warden; home, differently. Seeing the warden’s look, I thought I went too far — I was just a prison volunteer teaching art. But then he said something so uncharacteristic and with such sincerity, it knocked me silent. He said, “I hope you find what you are searching for in my prison.”

Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP), like all prisons, defined a person as an inmate 24/7. But structured prison space doesn’t just control identity; it destroys self by disrupting the interdependent relationship between an individual and space. There’s disorientation, spatial limitation, and a lack of personal belongings. It’s not surprising that maps, fantasy or real, are forbidden in any prison. That prisoners might escape hides the more basic concern: Maps connect a self to a place.

Of maps and memory

Memory is challenged in prison. On seeing the cramped space in which the men live, I asked another prison’s warden if memory of space was the largest dimension in prison. The warden answered, “No, memory of space is the first dimension the inmate loses.” Surprised, I wondered if the warden was referring to psychological loss — forgetting what my bedroom looks like, kitchen smells, neighborhood sounds? Or, whether the warden was referring to something more fundamental and therefore, more terrifying; what is a bedroom, a kitchen, a neighborhood?

Wandering ESP’s corridors with a map, contraband in any other prison, looking for artist Jesse Krimes’s installation, I wondered what powers a nonfunctioning prison still maintains.

Krimes’s 39-bedsheet mural, “Apokalupstein16389067: ii,” created while serving 70 months for a nonviolent crime, is the model for this ESP installation. Using drawing and offset images worked on bedsheets and adhered to the walls of the cell, the work presents as a horizontal triptych of heaven, earth, and, at the bottom, a congested hell. Entering the cell, I immediately think of frescoes on monks’ cells at St Marks, Florence, or the Giotto chapel. The mural is influenced by the concept of non-sites, the metaphoric space between a representation and that which it represents, say, between ESP’s map and the actual prison. What is this space of non-being where all and nothing is possible?

Krimes’s art is strong had it been created anywhere. That he develops such work while living in prison is remarkable. Despite prison’s capacity to make people, even trained artists, forget who they are, Krimes seems never to have lost experience of himself as an artist first, knowing art as a way of being. As such, art is not an escape from prison but the way through it.

Sound and vision

Jess Perlitz’s installation, “Chorus,” is the recording of individual prisoners singing in answer to her question, “If you could sing one song and have that song heard, what would you sing?” An audio tour directs the listener via to each song, enabling visitors to hear them individually.

“Beware of the Lily Law,” is Michelle Handelman’s powerful short film monologue portrayed by an actor playing the role of a transgender prisoner and presented on the decaying wall of a single cell.

Several installations make social commentary on prison. Two are Ruth Scott Blackson’s painted gold chips adhered to one cell’s wall, and, in another cell, Tyler Held’s stripped-down automobile. Blackson’s stated intention is to “entice the visitor to concentrate on the walls the same way a person in solitary confinement would.” Held’s stripped vehicle is intended to suggest the reduction of a prisoner to an object.

My experience of solitary confinement is that prisoners don’t see cell walls in the kind of contemplation Blackson suggests; they’re not seen, they’re endured, and as such, do not offer reflective vision. Contemplation such as praying is more often used to remove the walls. Likewise, making the analogy between prisoner and stripped-down automobile is too simplistic for what happens during incarceration. Prisoners go through an ontological sea change, whereas the car always was and will always be an object.

These walls can talk

The weakness of commentary installations is that ESP’s walls don’t need artists speaking for them. In fact, they scream of incarceration, and artists conceptualizing the walls make the installations pedantic, pretentious, and patronizing. At ESP, time, not artists, bring to the surface the metaphoric manifestations of prison’s annihilation of identity. Festering walls speak of neglect, abuse, fear, loneliness, and so on.

The museum makes an important decision by including artists. Yet, like prisoners, art becomes powerless when forced 24/7 into a single concept. Krimes’s, Handelman’s, and Perlitz’s works are effective in this space because their artistic merit works beyond prison’s walls. I first saw Handelman’s film in an auditorium, Krimes’s mural at Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, and Perlitz’s recorded songs could be appreciated on any audio system. Contrary to commentary, this art transcends the prison’s exclusive power to define. In helping the visitor move through space, without eluding issues of incarceration, art becomes transformative rather than informative, moving to a metaphoric expanse of infinite possibility.

What, When, Where

"Apokalupstein16389067: ii," by Jesse Krimes; "Chorus," by Jess Perlitz; "Beware of the Lily Law," by Michelle Handelman; "No Trace without Resistance," by Ruth Scott Blackson; "Identity Control," by Tyler Held. These and other artist installations remain through May 2017 at Eastern State Penitentiary, 2027 Fairmount Ave., Philadelphia. (215) 236-3300 or easternstate.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Treacy Ziegler

Treacy Ziegler