Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

America's Indian tragedy: A path not taken (and a lesson from the French)

Whites vs. Indians: a better way

As I expected, some BSR readers took me to task for suggesting, two weeks ago, that American Indians' moral claim to the North American continent wasn't all that solid. A relatively small number of Indians, I pointed out, monopolized all that land for hunting because they never got around to mastering agriculture or domesticating animals for food, milk and transportation. (See "Samuel Colt's revolver: A mixed blessing.")

I might have added that, with few exceptions, pre-literate Indian tribes lacked the critical ability to manipulate abstract symbols— letters written on paper— that enabled Europeans to spread knowledge and, in the process, create money, credit, securities, insurance, machines, buildings, railroads, bridges and all the other tools that enable advanced societies to render land more beneficial for greater numbers of people.

To be sure, anyone who has researched the opening of the American West— as I did for my most recent book, Death of a Gunfighter— must come away appalled by the brutality with which American Indians were forcibly removed from land they had occupied for some 10,000 years. From the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, the story of American settlement is largely the story of government's failure or unwillingness to prevent white settlers from pushing the outnumbered and outgunned Indians ever farther westward— even the so-called "five civilized tribes" of Florida, whose people, contrary to conventional stereotypes, had by 1830 embraced many aspects of civilized white culture, including European clothing and names, wood frame houses, modern farming methods, and even the Roman alphabet and representative government.

The Indian Relocation Act of 1830 guaranteed Indians all the land west of the Mississippi River, but that pledge vanished with the California Gold Rush of 1849. In 1851, after a council of 10,000 Plains Indians met for three weeks with American politicians in what is now Wyoming, the tribes accepted guaranteed hunting rights only through the area that subsequently became Wyoming and Montana. In exchange they were promised annuities and supplies. That pledge too was ultimately broken.

Their violence and ours

For all their apparent differences, Indians and white frontiersmen did seem (at least at the time) to share one common characteristic: a preoccupation with honor, vengeance and violence. The Kiowa chief Satanta, while leading a massacre in 1871, tied a teamster to a wagon wheel and cheerfully roasted him; then he rode to nearby Fort Sill, where he bragged to a U.S. Indian agent about the torture. Rachel Plummer, a pregnant woman captured by Comanches, suffered the trauma, as soon as her baby was delivered, of seeing it dragged to death behind a horse.

Yet most of the violence between the two cultures was initiated by whites, who employed against the Indians such weapons and tactics as poisoned meat and drink, smallpox-infected blankets, booby-trapped bodies, dogs unleashed on captives, and the execution of the wounded as well as women and children. Except for a few tribes (like the Apaches, who had lived for generations by raiding their neighbors' camps), the Indians as a rule fought only in retaliation, when white men invaded their hunting grounds.

All for a sick cow

In 1854, as a tribe of Brulé Lakota camped just east of Fort Laramie (now Wyoming) while awaiting their government annuities, an Indian named High Forehead, camping with the Brulé, shot a lame cow belonging to a passing group of emigrants along the Oregon Trail. When the emigrants complained to the post commander, he tried to let the matter slide for the sake of peaceful relations with the Indians. But an impulsive lieutenant fresh out of West Point named John Grattan insisted on arresting High Forehead.

Grattan took a detachment of 30 men to the Brulé camp and proceeded to parley with the Brulé leader, Conquering Bear, through an interpreter who is described in various accounts as drunk, malicious or both. Conquering Bear offered to exchange horses for the sick cow but refused to surrender High Forehead.

Jeff Davis's other war

Lieutenant Grattan foolishly rejected this reasonable offer; an argument ensued; and a shot was fired, possibly by accident. In the ensuing firefight, Conquering Bear was shot down, even as he sought to calm both sides. Grattan and his 30 soldiers, greatly outnumbered, were surrounded and decimated.

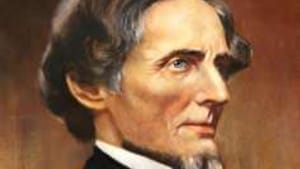

Rather than exacerbate the situation by retaliating, Army officials diplomatically declared that Lieutenant Grattan had exceeded his authority. Yet a year later, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis— yes, that Jefferson Davis— announced that this "Grattan Massacre" must be avenged with a show of force. In this manner, a dispute over the shooting of a sick cow mushroomed into 40 years of so-called "Indian Wars"— the longest and most tragic military campaign in American history.

Eloquent lamentations

From the start, most Indian leaders saw the writing on the wall and so bowed to the inevitable. The essence of their eloquent lamentations during that era can be boiled down to a single rhetorical question: "By what right do you intrude upon our land and the way of life we have pursued for generations?"

Because 19th-Century whites were endowed with greater numbers, better arms and more advanced technology, they never really addressed that question. Yet a reasonable moral response to the Indians did indeed exist, if any white leader had bothered to articulate it:

"By what right do you monopolize this land for yourselves in perpetuity? Who appointed you sole judge as to the wisest stewardship of this land? By what right do you, whose ancestors came here long ago in search of a new life, deny others the same opportunity?"

British settlers vs. French

But beyond the question of moral right lies a more intriguing question: Was warfare the only solution to the conflicting needs of whites and Indians? Was there no better way?

As a matter of fact, there was. The whites who settled the American West represented not one European culture but two: the British— a term that embraces Englishmen, Scots and Irish— and the French. The values and motives of these two cultures— and consequently their posture toward Indians— differed radically.

If I may generalize broadly: The British settlers were ambitious, individualistic, aggressive, land-hungry and bigoted. The French, by contrast, were complacent, communal, peaceful, social and tolerant.

Who is nobler?

The French, in the tradition of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, admired the "noble savage" as the supreme examplar of man in his natural (and therefore uncorrupted) state; the English, by contrast, esteemed civility, a condition that required inhibiting one's natural "savage" instincts by submerging them behind clothing, haircuts, neat homes in fixed locations and other demonstrations of submission to the general order. That is, the French looked up to the Indians; the British looked down.

The first British colonists, driven here by a population explosion in 17th-Century England, hungered to acquire America's vast arable lands. Their descendants, still preoccupied with seizing, developing and speculating in land, regarded Indians as peripheral to their plans— savage nuisances at best and deadly enemies at worst. The French settlers, on the other hand, demonstrated little inclination to create new settlements or tame new stretches of wilderness.

Chatting through windows

So where the English segregated themselves from the Indians (whom they considered an inferior race), the French lived among the Indians, often intermarried with them, and treated differences of race and color as accidents of minor importance.

Where the individualistic English cherished huge spreads of land to separate themselves from their neighbors, the more social French created compact villages where land was owned communally and streets were deliberately laid out as narrowly as possible, the better to facilitate neighborly conversation from one cottage window to another (much like my neighbors in my Center City alley/street).

In retrospect it's tempting to suggest that America's entire 19th-Century Indian tragedy might have been avoided if the British had lost the French and Indian War. In that case, the American West might have been settled predominantly not by ambitious and belligerent land-hungry Englishmen but by contented and sociable Frenchmen.

But regardless of who won that war, ultimately the sheer numbers of British immigrants would have overwhelmed the French in America. Lacking land at home, the British had good reason to emigrate to America and then head West; the French, for the most part, did not.

And if the French had outnumbered the British in America, the "Great American Desert"— as the entire expanse between the Missouri River and California was labeled on maps as late as the 1840s— might still be a desert today. For it was the aggressive and bigoted English, not the humane and enlightened French (and certainly not the Indians, whose culture lacked any concept of progress), who possessed the ambition and audacity to transform the West into something different than it had been. In the West, as elsewhere, there never was such a thing as an unmixed blessing.♦

To read a response, click here.

I might have added that, with few exceptions, pre-literate Indian tribes lacked the critical ability to manipulate abstract symbols— letters written on paper— that enabled Europeans to spread knowledge and, in the process, create money, credit, securities, insurance, machines, buildings, railroads, bridges and all the other tools that enable advanced societies to render land more beneficial for greater numbers of people.

To be sure, anyone who has researched the opening of the American West— as I did for my most recent book, Death of a Gunfighter— must come away appalled by the brutality with which American Indians were forcibly removed from land they had occupied for some 10,000 years. From the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, the story of American settlement is largely the story of government's failure or unwillingness to prevent white settlers from pushing the outnumbered and outgunned Indians ever farther westward— even the so-called "five civilized tribes" of Florida, whose people, contrary to conventional stereotypes, had by 1830 embraced many aspects of civilized white culture, including European clothing and names, wood frame houses, modern farming methods, and even the Roman alphabet and representative government.

The Indian Relocation Act of 1830 guaranteed Indians all the land west of the Mississippi River, but that pledge vanished with the California Gold Rush of 1849. In 1851, after a council of 10,000 Plains Indians met for three weeks with American politicians in what is now Wyoming, the tribes accepted guaranteed hunting rights only through the area that subsequently became Wyoming and Montana. In exchange they were promised annuities and supplies. That pledge too was ultimately broken.

Their violence and ours

For all their apparent differences, Indians and white frontiersmen did seem (at least at the time) to share one common characteristic: a preoccupation with honor, vengeance and violence. The Kiowa chief Satanta, while leading a massacre in 1871, tied a teamster to a wagon wheel and cheerfully roasted him; then he rode to nearby Fort Sill, where he bragged to a U.S. Indian agent about the torture. Rachel Plummer, a pregnant woman captured by Comanches, suffered the trauma, as soon as her baby was delivered, of seeing it dragged to death behind a horse.

Yet most of the violence between the two cultures was initiated by whites, who employed against the Indians such weapons and tactics as poisoned meat and drink, smallpox-infected blankets, booby-trapped bodies, dogs unleashed on captives, and the execution of the wounded as well as women and children. Except for a few tribes (like the Apaches, who had lived for generations by raiding their neighbors' camps), the Indians as a rule fought only in retaliation, when white men invaded their hunting grounds.

All for a sick cow

In 1854, as a tribe of Brulé Lakota camped just east of Fort Laramie (now Wyoming) while awaiting their government annuities, an Indian named High Forehead, camping with the Brulé, shot a lame cow belonging to a passing group of emigrants along the Oregon Trail. When the emigrants complained to the post commander, he tried to let the matter slide for the sake of peaceful relations with the Indians. But an impulsive lieutenant fresh out of West Point named John Grattan insisted on arresting High Forehead.

Grattan took a detachment of 30 men to the Brulé camp and proceeded to parley with the Brulé leader, Conquering Bear, through an interpreter who is described in various accounts as drunk, malicious or both. Conquering Bear offered to exchange horses for the sick cow but refused to surrender High Forehead.

Jeff Davis's other war

Lieutenant Grattan foolishly rejected this reasonable offer; an argument ensued; and a shot was fired, possibly by accident. In the ensuing firefight, Conquering Bear was shot down, even as he sought to calm both sides. Grattan and his 30 soldiers, greatly outnumbered, were surrounded and decimated.

Rather than exacerbate the situation by retaliating, Army officials diplomatically declared that Lieutenant Grattan had exceeded his authority. Yet a year later, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis— yes, that Jefferson Davis— announced that this "Grattan Massacre" must be avenged with a show of force. In this manner, a dispute over the shooting of a sick cow mushroomed into 40 years of so-called "Indian Wars"— the longest and most tragic military campaign in American history.

Eloquent lamentations

From the start, most Indian leaders saw the writing on the wall and so bowed to the inevitable. The essence of their eloquent lamentations during that era can be boiled down to a single rhetorical question: "By what right do you intrude upon our land and the way of life we have pursued for generations?"

Because 19th-Century whites were endowed with greater numbers, better arms and more advanced technology, they never really addressed that question. Yet a reasonable moral response to the Indians did indeed exist, if any white leader had bothered to articulate it:

"By what right do you monopolize this land for yourselves in perpetuity? Who appointed you sole judge as to the wisest stewardship of this land? By what right do you, whose ancestors came here long ago in search of a new life, deny others the same opportunity?"

British settlers vs. French

But beyond the question of moral right lies a more intriguing question: Was warfare the only solution to the conflicting needs of whites and Indians? Was there no better way?

As a matter of fact, there was. The whites who settled the American West represented not one European culture but two: the British— a term that embraces Englishmen, Scots and Irish— and the French. The values and motives of these two cultures— and consequently their posture toward Indians— differed radically.

If I may generalize broadly: The British settlers were ambitious, individualistic, aggressive, land-hungry and bigoted. The French, by contrast, were complacent, communal, peaceful, social and tolerant.

Who is nobler?

The French, in the tradition of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, admired the "noble savage" as the supreme examplar of man in his natural (and therefore uncorrupted) state; the English, by contrast, esteemed civility, a condition that required inhibiting one's natural "savage" instincts by submerging them behind clothing, haircuts, neat homes in fixed locations and other demonstrations of submission to the general order. That is, the French looked up to the Indians; the British looked down.

The first British colonists, driven here by a population explosion in 17th-Century England, hungered to acquire America's vast arable lands. Their descendants, still preoccupied with seizing, developing and speculating in land, regarded Indians as peripheral to their plans— savage nuisances at best and deadly enemies at worst. The French settlers, on the other hand, demonstrated little inclination to create new settlements or tame new stretches of wilderness.

Chatting through windows

So where the English segregated themselves from the Indians (whom they considered an inferior race), the French lived among the Indians, often intermarried with them, and treated differences of race and color as accidents of minor importance.

Where the individualistic English cherished huge spreads of land to separate themselves from their neighbors, the more social French created compact villages where land was owned communally and streets were deliberately laid out as narrowly as possible, the better to facilitate neighborly conversation from one cottage window to another (much like my neighbors in my Center City alley/street).

In retrospect it's tempting to suggest that America's entire 19th-Century Indian tragedy might have been avoided if the British had lost the French and Indian War. In that case, the American West might have been settled predominantly not by ambitious and belligerent land-hungry Englishmen but by contented and sociable Frenchmen.

But regardless of who won that war, ultimately the sheer numbers of British immigrants would have overwhelmed the French in America. Lacking land at home, the British had good reason to emigrate to America and then head West; the French, for the most part, did not.

And if the French had outnumbered the British in America, the "Great American Desert"— as the entire expanse between the Missouri River and California was labeled on maps as late as the 1840s— might still be a desert today. For it was the aggressive and bigoted English, not the humane and enlightened French (and certainly not the Indians, whose culture lacked any concept of progress), who possessed the ambition and audacity to transform the West into something different than it had been. In the West, as elsewhere, there never was such a thing as an unmixed blessing.♦

To read a response, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg