Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Are you ready for the Whig revolution?

The Whig tradition, according to David Brooks

With his customarily loony perspicacity, David Brooks of the New York Times has concluded that President Obama’s best bet for establishing a legacy during his remaining three years in office lies in creating an “Opportunity Coalition” that will cut across ideological lines in order to “formulate, lobby for, fund and promote opportunity and social mobility agendas for decades to come.” (Click here.)

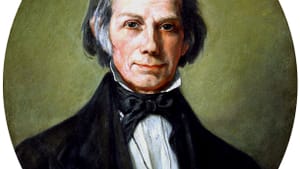

Instead of embracing America’s liberal or conservative traditions, Brooks suggests, Obama should choose “a third ancient tradition...the Whig tradition, which began with people like Henry Clay, Daniel Webster and Abraham Lincoln."

Brooks neglects to mention that the Whig tradition also ended with people like Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Abraham Lincoln. Webster ran for president three times without success. So did Clay. Lincoln touched the nation’s soul and reached the White House only in another guise — as a Republican — after the Whig Party expired in the 1850s over its inability to grapple with the critical question of its age: whether to allow slavery to expand into America’s Western territories. The Whig Party didn’t last “for decades to come”: it lasted three decades, period.

The Whigs were essentially decent fellows whose theories never quite worked out in practice (they believed, for example, in a strong government but a weak presidency). They did manage to elect two presidents, William Henry Harrison in 1840 and Zachary Taylor in 1848, neither of whom survived in office long enough to be cited as a role model by the likes of David Brooks. Their respective successors as president were even less inspiring: Once in the White House, John Tyler opposed the Whig platform, vetoed several Whig proposals, and consequently was expelled from the Whig Party; he finished his career as a Confederate congressman. Zachary Taylor’s successor, Millard Fillmore, was refused renomination by his own party in 1852 and ran for president in 1856 under the aegis of the American Party, the political arm of the anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic "Know-Nothing" movement. Whenever historians gather to rate American presidents, all four Whig presidents are consistently ranked in the bottom ten.

As seems to be his custom, Brooks’s encomium to Whiggery ignores the critical question: Why did such thoughtful, rational gentlemen fail to seize the public’s imagination, and why did their populist bête noir Andrew Jackson succeed? It won’t do simply to dismiss Jackson as a charismatic bumpkin. In the formulation of the ancient Greek poet Archilochus — “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing” — the Whigs were the foxes, and Jackson was the hedgehog. His Big Thing was this: The way things are is not the way things have to be. Individually or collectively, you possess the power to change the world. That message continues to inspire people (myself included) in all places and aspects of life — from politics to religion to the arts. It’s the missing ingredient that explains why the Whigs, for all their good sense, never gained traction.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg