Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

. . . And how do you feel about Tchaikovsky, Mr. Putin?

Putin’s Russian dreams

Six weeks after itemizing his country’s remarkable cultural glories at the opening of the Sochi Winter Olympics, Russian president Vladimir Putin justified his country’s seizure of the Crimean peninsula with a very different list: a bitter recitation of Russia’s grievances at the hands of the West.

“They cheated us again and again, made decisions behind our back, presenting us with completed facts,” Putin declared before members of Parliament and government officials. “That’s the way it was with the expansion of NATO in the East, with the deployment of military infrastructure at our borders. They always told us the same thing: ‘Well, this doesn’t involve you.’” To make amends, Putin promised to restore Russia’s “military glory and outstanding valor.”

These two presentations six weeks apart raise an intriguing psychological question: How could such an artistically superior civilization suffer from such an inferiority complex?

The answer may lie in a closer examination of the 11 Russian writers, composers, artists, and filmmakers who were singled out for recognition in “Dreams of Russia,” the opening extravaganza at Sochi. Without exception, these unquestionably brilliant Russians flourished artistically despite their government, not because of it. Indeed, many of them fulfilled their creative potential only by leaving Russia altogether.

Sent to Siberia

— Alexander Pushkin wrote his most famous play, the drama Boris Godunov, at a time when he was under the strict surveillance of the Tsar's political police and unable to publish.

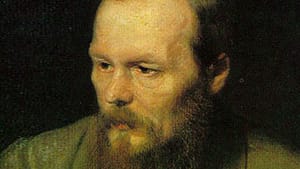

— Fyodor Dostoyevsky was arrested in 1849 for his involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle, a secret society of liberal utopians that also functioned as a literary discussion group. He and other members were condemned to death, but at the last moment, a note from Tsar Nicholas I was delivered to the scene of the firing squad, commuting their sentences to four years' hard labor in Siberia.

— Leo Tolstoy’s experiences in 19th-century Russia molded him into an outspoken pacifist and anarchist. "The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens,” he once wrote. “Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere.”

— Pytor Tchaikovsky was a musical prodigy, but he was educated for a career as a civil servant because Russia in his youth offered no system of public music education and little opportunity for a musical career. Not until he was in his 20s did Tchaikovsky enter the newly created St. Petersburg Conservatory — which offered Western-oriented teaching that blessedly distinguished him from the Russian nationalist composers of his day. Oh — did I mention that Tchaikovsky was gay? Do you dare to imagine how Tchaikovsky would manage in Putin’s Russia?

Instinct to flee

— Anton Chekhov attended a school for Greek boys (not Russians) and sang in a Greek monastery. As an adult he became an atheist and an outspoken critic of the Russian government’s mistreatment of convicts.

— The pioneering abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky settled in Munich in 1896, when he was 30, and returned to Moscow in 1914, but left Russia for good in 1921 and became a citizen of France, where he produced his best work until his death in 1944.

— Vladimir Nabokov fled Bolshevik Russia with his family in 1919. He studied at Cambridge and spent the rest of his life in Germany, the United States, and Switzerland. Although his early novels were written in Russian, he achieved international prominence as a writer of English prose.

— Marc Chagall left Russia in 1922, when he was 35, and thereafter lived in the United States and France.

Stalin’s shadow

— Sergei Eisenstein, the great Soviet film director, went to Hollywood and Mexico in 1928 to polish his craft. When he returned to Russia in 1930, he discovered that his foray to the west had earned the disfavor of Russia’s staunchly Stalinist film industry. The official suspicion of his loyalty never quite evaporated, and in 1933 Eisenstein wound up in a mental hospital.

— Kazimir Malevich, a pioneer of geometric abstract art, was denounced as a counterrevolutionary after Stalin succeeded Lenin in 1924; he was banned from creating or exhibiting further artworks.

— Alexander Rodchenko, a pioneer of abstract and socially engaged photography, switched to sports photography and images of parades in the 1930s after the Soviet Communist Party reprimanded him.

— The artist/designer/typographer El Lissitzky, another pioneer of avant-garde art, similarly fell afoul of Stalin’s guidelines in 1932 and subsequently survived by creating a new career as a pioneer of propaganda as art during World War II.

(I know — last month’s Sochi celebration overlooked Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Nijinsky, Solzhenitsyn, and Gogol. But none of them could be described as a champion of the motherland, either.)

Queen Elizabeth’s lesson

Were any of these creative innovators alive in Russia today, most would likely be languishing in Putin’s prisons. For Russia to take credit for these geniuses would be like Bostonians taking credit for Ben Franklin. He was born there, yes, but Franklin thrived only after he fled Boston’s stifling Puritan confines for Philadelphia’s more tolerant Quaker environment.

Artistic creativity flourishes in those rare societies — Periclean Athens, Elizabethan England, modern-day America — whose leaders perceive that their own positions will be more secure if their citizens are happy and free. Putin, by contrast, believes that what makes Russians happy is the glory of their government and military. And there may be something to that notion: As his nemesis Mikhail Khodorkovsky recently observed (after Putin arbitrarily released him from prison), the real problem with Russia is not Putin but an inbred authoritarian mindset that predates Putin and Communism as well.

Putin now contends that his government is obligated to protect not only Russian citizens but also Russian speakers everywhere. This is like suggesting that Queen Elizabeth should look out for America’s Anglo-Saxon Protestants. As Putin’s own Sochi catalog of great Russian artists attests, the world beyond Russia’s borders is in fact full of native Russians, most of whom want nothing to do with Putin’s Russia. Nearly a million live in the U.S.; more than 1 million live in Israel; and, yes, many more millions live in Ukraine, the land Putin now threatens to protect.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg