Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

An open letter to three high school editors

Neshaminy’s high school press dispute

Dear Gillian McGoldrick, Jackson Haines, and Reed Hennessy:

Congratulations for passing, at the tender age of 17, a critical milestone in the process of growing up — namely, the discovery that adults don’t really know what the hell they’re doing.

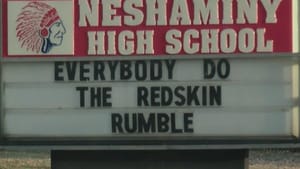

As editors of the school newspaper at Neshaminy High School in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, you concluded last fall that the school’s mascot — the “Redskin” — was a symbol derogatory to Native Americans, and therefore you would not allow the word in the paper’s pages. This is the sort of editorial judgment that many mature and sensitive people would applaud but that some hidebound and childish grown-ups — the owners of the Washington Redskins, the Cleveland Indians, and the Atlanta Braves spring to mind — still stubbornly resist.

In most schools these days, educators are concerned about discouraging offensive language, not perpetuating it. Even if they found your experiment flawed or downright misguided, most educators would welcome it as a teachable moment.

Nevertheless, your principal, Rob McGee, responded by rescinding your ban. Your refusal to print the word "Redskin," he reasoned, could infringe on the First Amendment rights of those who wanted to use the word, especially since the Neshaminy High Playwickian is published with public funds. In the best educational tradition of letting kids learn from their real-life experiences, he even hinted that he might sic the police on you.

Adolescent brains

In due course, Principal McGee confiscated copies of your paper, you hired lawyers, and last week the Neshaminy school board, in its solomonic wisdom, approved a policy that will allow you to remove the word "Redskin" from news articles but not from editorials or opinion columns. (They deferred judgment on the use of “nigger,” “Jewboy,” and “wop.”) Also, you and your staff have been locked out of your newspaper’s email and social media accounts, and you’re now required to submit articles to school administrators ten days before publication instead of three.

And you thought George Norcross was meddling with the Philadelphia Inquirer.

These protective measures are necessary because, as modern science recently discovered, at age 17 your synapses aren't yet totally functioning. Consequently, as Professor Richard Friedman of Weill Cornell Medical College explained in Sunday’s New York Times, “Adolescents have a brain that is wired with an enhanced capacity for fear and anxiety, but is relatively underdeveloped when it comes to calm reasoning.”

The good news is: You at least have an excuse for your behavior. The same can’t be said for Principal McGee or the Neshaminy school board members. Nor, of course, can it be said for other adults, like Governor Christie’s officials in New Jersey who created a traffic jam as retribution against a political foe; or George W. Bush, who responded to al-Qaeda’s militaristic threats by declaring, “Bring ’em on!”; or Vladimir Putin, who has a penchant for posing bare-chested on horseback.

Vietnam controversy

The truly good news, as you approach your senior year, is that a simple solution to your quandary is at hand: Resign from the school paper and start your own.

I do not speak facetiously. My cousin Andy Lichterman once did the very same thing, with inspiring results — specifically, he drove his school paper out of business.

During the 1968-69 school year, at the height of the Vietnam War, Andy was a junior editor and heir apparent of his high school paper in Niskayuna, New York, a suburb of Schenectady. When the scheduled screening of an antiwar film in the school’s assembly was criticized by the local American Legion, the principal canceled the film on the ground that it told only one side of the war story. Andy responded with an editorial that criticized the principal but was notable for its restraint: It acknowledged the pressures that small communities can exert on a principal and the difficulty of satisfying all parties in such a contentious issue. Precisely because the editorial couldn’t be dismissed as the babbling of an overheated teenager, the principal refused to publish it.

Faculty attack

Andy, along with most of the staff, reacted by quitting the paper. Instead, they raised funds from their classmates and launched their own competing newspaper, printed on a mimeograph machine (no Internet in those days). With All Due Respect, as they named their paper, quickly became a lively forum for discussion of issues about the school, not to mention the larger society. It seized the imagination of the students in a way that the adult-controlled school paper couldn’t. Before long, most students stopped reading the school paper altogether.

To be sure, it helped that these kids were probably brighter and more creative than their teachers and administrators. At one point, the school paper’s frustrated faculty sponsor published an angry editorial, attacking With All Due Respect for wasting time and energy on a divisive publication. Andy’s paper responded by reprinting the teacher’s editorial in its entirety — “for the benefit of our readers who haven’t seen it” — and pointing out that the wasteful party was, in fact, the school, which was spending public funds to produce “a paper that nobody wants to read.”

At the end of the year, the embarrassed principal threw in the towel. He invited Andy to return to the school paper for his senior year on his own conditions, with no constraints. Presumably he realized he had no choice: Andy would be kicking him around, whether he was on the reservation or off. That's how free speech works.

College rejections

Unlike Andy, you three no longer need a mimeograph machine to reach your classmates. The Internet gives you a forum at virtually no cost. If you’re like most 17-year-olds I know, you’re way ahead of your elders on the technology curve. Why not exploit your advantage?

Did Andy pay a price for his defiance of school authorities? To some extent, yes. When Andy applied to colleges as a senior, no one on the faculty gave him much of a positive recommendation. Of seven colleges that Andy applied to, only one accepted him. Fortunately for Andy, that college was Yale. Today, he’s a public policy lawyer in California, focusing on nuclear disarmament and speaking truth to power much as he did at Niskayuna High School more than 40 years ago.

To this day, the back issues of With All Due Respect occupy a place of honor in my garage. From time to time, I pull them out to remind myself why I became a journalist in the first place. I’d love to show them to you. From what I’ve read and heard, you may well learn more from Andy’s paper than from the grown-ups in Neshaminy.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg