Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

When the lamb attacked the butcher (and other great moments in sport)

My favorite sports memories

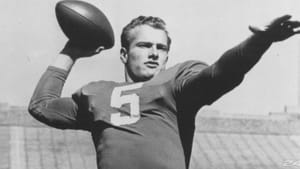

Any TV producer, newspaper editor, or museum curator will tell you: Nothing boosts circulation or attendance like sports. (To consider the National Museum of American Jewish History’s current effort, click here.) Even between seasons (like now), sportswriters churn out reminiscences of their favorite sports memories — usually heroic triumphs, awesome upsets, and stunning comebacks.

For a change of pace, I offer here my own idiosyncratic list of ten favorite sports memories from my years as a player, sportswriter, and fan. As you will see, I’m a sucker for displays of ingenuity, character, and persistence against overwhelming odds; and amateurs excite me more than professionals. To heighten the suspense, I’ve listed my top ten in reverse order. The envelopes, please:

10. Joan of Arc redux (New York, 1957). In Fieldston School’s intramural LAKE League (an acronym for the Ethical Culture Society’s patriarchs Lewis, Adler, Kelly, and Elliott), Lewis had the ninth grade’s two best basketball players but no one else worthy of the name. The day before the championship game, the Lewis team’s star player was stricken with appendicitis. Then, 15 seconds into the big game, the Lewis team’s second-best player was ejected for arguing with the referee. Lewis seemed doomed. But at this dismal point, a short, chunky and previously unheralded second-stringer named Peter Heiman leaped off the bench and, much like Joan of Arc at Orléans, rallied his demoralized teammates to a stunning upset victory over mighty Kelly.

9. The ultimate satisfaction (Riverside Park, New York, c. 1957 or ’58). A half-court four-on-four pickup basketball game; I was in ninth or tenth grade. One of my teammates was a local wise guy, bigger than everyone else on the court. Whenever someone missed a shot, he’d grab the rebound, dribble back to the foul line and take a shot, ignoring his teammates altogether, to my great frustration.

“Pass the damn ball!” I shouted at this dude. “Look for the open man!”

“You think you’re so great, smart guy?” he replied. “Let’s see how well you do without me.” With that he ambled to the sideline, smirking, leaving my two remaining teammates and me to play against four men while trailing by two baskets.

“OK, let’s see!” I replied defiantly. We came from behind, won the game and, not incidentally, wiped the smirk off that hood’s face.

8. A teachable moment (Fieldston School, New York, October 1955). In the last regular-season football game of Fieldston’s eighth-grade intramural LAKE League (see above), Kelly broke a scoreless tie against Adler with a touchdown pass on the game’s final play. The Adler players protested that the receiver had bobbled the ball and hadn’t gained full possession until he was out of the end zone. They argued so vehemently that the referee/gym teacher, Alton Smith, decided to teach them a lesson. He nullified Kelly’s touchdown but instead decreed that Kelly’s final series of four downs would be replayed the next day, from the Adler one-yard line. In that replay, Kelly’s quarterback, Tom Strauss, attempted four consecutive quarterback sneaks, and each time the Adler line held, preserving the tie and clinching the league championship. (Strauss, presumably chastened by this experience, grew up to become president of Salomon Brothers, the major Wall Street investment house.)

7. A few good men (Gas City, Indiana, August 1965). With two out and the score tied in the bottom of the ninth inning between the semi-pro Portland Rockets and the host Gas City Bankers, the umpire walked off the field rather than endure further razzing from the local fans. The two bewildered teams agreed to finish the game two weeks later, leaving the Rockets’ manager, Dick Runkle, with the challenge of finding nine players willing to drive an hour each way to face, possibly, just one batter. He found only seven, none of them a catcher. Rather than forfeit the game, Runkle, whose playing days were long over, improvised by positioning himself at first base, putting an outfielder behind home plate, and sticking a decidedly nonathletic friend in right field in the hope that no one would hit a ball in his direction. Mercifully, the Rockets escaped the ninth inning with the bases loaded and then scored a run in the tenth inning to win the game.

6. John Bajusz’s classy farewell (Palestra, Philadelphia, February 1986). Against Penn, Bajusz — one of the greatest basketball players in Cornell history — found himself double-teamed throughout the game. Every time he got the ball, two Penn defenders stuck their hands in his face. Bajusz managed to take just 12 shots the entire game but somehow made nine of them. He took six free throws and made all of them. Throughout the game the lead swung back and forth, but with less than a minute to play and Penn leading by ten points, Cornell’s coach finally took Bajusz out. Instead of slinking to the sidelines, Bajusz sought out three nearby Penn players to shake their hands. Penn’s remaining two players were standing at the other end of the court; Bajusz ran to midcourt and waved them a salute before retiring.

5. A game plan that actually worked (New York, February 1960). I was co-captain of a moderately good Fieldston School team; McBurney was a private school powerhouse, especially in its own intimidating gym — a badly lit bandbox with one good basket, one bad basket, and an overhanging running track. The previous year we had lost there by 34 points. But my co-captain, Bob Liss, and I devised an ingenious game plan: We would take the “bad” basket for the first half and slow the game’s pace, hoping to stay within a few points at halftime, after which we’d benefit from the “good” basket in the second half. Thanks to this strategy, at halftime we trailed by only three points. And in the third quarter, everything we threw toward that wonderful “good” basket seemed to swish through, transforming our three-point halftime deficit into a nine-point lead. McBurney inevitably stormed back in the fourth quarter, but we managed to hang on and win by two points.

4. The lamb attacks the butcher (Franklin Field, Philadelphia, 1955). The nationally televised Penn-Notre Dame football game should have been one of the great mismatches of all time. Notre Dame was ranked fourth in the nation; Penn, handicapped by the new Ivy League restrictions against athletic scholarships and spring practice, had lost 15 consecutive games and had scored only two touchdowns in its first six games that season. Yet Penn sophomore Frank Riepl, who had never before started a college game, ran back the opening kickoff for a touchdown. His fired-up teammates proceeded to cause five Notre Dame fumbles, intercepted two passes, and had the game tied at halftime, 14-14. Notre Dame eventually won as expected. But as Louis Effrat put it in the New York Times, “The losers showed that determination, even in the face of hopeless task, could carry an outclassed squad a long way.”

3. Bart Leach’s confession (Palestra, Philadelphia, March, 1955). On the last weekend of the Ivy League basketball season, Penn and Columbia were battling for first place. Midway through their game, Penn’s magnificent star and captain, Bart Leach, knocked a Columbia shot out of the basket. When referee John Nucatola failed to notice his illegal goal-tend, Leach himself pointed it out to him, with the result that Columbia was awarded the basket. Ultimately the game went into overtime, Columbia won it, and the two teams finished in a three-way tie for first place with Princeton, which ultimately won the playoff — all, you could argue, because of Leach’s display of good sportsmanship above and beyond the call. (You won’t be surprised to learn that Leach later became a Presbyterian minister.)

2. The ultimate character test: Penn’s 2012 football team. To lose your best running back, your two best receivers, and ultimately your first-string quarterback; to lose all your non-league games; to lose (badly) to the worst team in the Ivy League and come close to losing to the other six teams as well; and yet to keep bouncing back, week after week, to wind up with an overall winning record and an undisputed Ivy League championship, finishing ahead of one of the most awesome teams in Harvard history — a nationally ranked squad that broke virtually every Ivy League offensive and defensive record — it boggles the mind. The morning after the season ended, I suspect players and fans from the other seven Ivy schools were scratching their heads and saying, “Those guys won the Ivy League?” But those guys really did.

1. The frozen basketball team (Winchester, Indiana, February 1965): On the first night of the annual Indiana high school basketball tournament, a statewide blizzard forced the postponement of all but four of the state’s 64 sectional tournaments. One exception was the opening doubleheader at Winchester. Of the four schools scheduled to play there that night, one — Madison Township — was a rural school whose players were snowed in to their homes on impassable county roads. Madison’s coach, Jeff Coffel, arrived half an hour before the game to find just three of his players present. While waiting desperately for reinforcements, he asked the rival Ridgeville coach as well as tournament officials to postpone the game. They declined. By game time, just six Madison varsity players were on hand, of whom only three were starters, and none had had more than a few minutes to warm up. Coffel resigned himself to certain defeat.

Then the game started. Incredibly, this cold and decimated Madison contingent jumped off to a 16-0 lead and never let up, ultimately winning by the lopsided score of 83-55. One missing Madison starter, having shoveled his way out of his home, arrived in time to score seven points in the second half.

Coffel’s most challenging problem, it turned out, was getting home after the game: His car (like mine) got mired in a snowdrift and had to be plowed out by the state highway patrol.

To read a follow-up by Dan Rottenberg, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg