Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Main Street revisited

Let's redefine the American small town

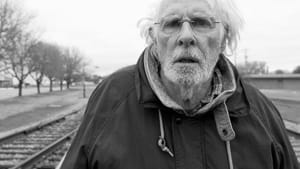

Ricky Ian Gordon’s new opera, A Coffin in Egypt, concerns a demented 90-year-old widow (played here this month by Frederica von Stade) who’s condemned to recall her salad days in New York and Paris while bitterly winding down her life in an isolated Texas town. In Alexander Payne’s 2013 film Nebraska, a demented octogenarian (Bruce Dern) returns to his hometown after many years to find that his former neighbors and relatives are even more narrow-minded, tiresome, and out to lunch than he is.

Welcome to the 21st-century world of arts and culture, where the American small town continues to serve as a convenient shorthand for conformity and drudgery. As the two examples above suggest, it’s virtually impossible today to imagine that there once was a time — say, back in the age of Jefferson and Jackson — when small towns were routinely perceived as the wellsprings of American creativity, and cities were seen as breeding grounds for parasites who lived off the productive classes out in the country.

“People here earned a living by mercantile work,” the coal entrepreneur Josiah White wrote disparagingly of Philadelphia upon his arrival from rural New Jersey as a teenage apprentice in 1796, “but at home by farming.”

Two women, two views

That rural conceit was permanently (and properly) shattered by Sinclair Lewis in 1920 with the publication of his satirical novel Main Street. Lewis’s portrait was so devastating that small towns have persisted as convenient symbols for backwater isolation and decay ever since. Who can forget the dead-on moment when the city-bred protagonist, Carol Kennicott, arrives in Gopher Prairie, Minnesota and inspects with dismay the town's physical ugliness and stolid dullness — as country girl Bea Sorenson arrives in the same town on the same day and pronounces it the most beautiful and exciting place she’s ever seen?

Yet even as Main Street became a major best seller of its time — it sold 250,000 copies in its first six months — the isolated world it lampooned was disappearing, thanks to telephones, radio, and automobiles. Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee caught that shift astutely in their 1955 play Inherit the Wind, set in a small Tennessee town and based on the Scopes evolution trial of 1925 — just five years after Main Street appeared. When the minister’s daughter praises the prosecutor Matthew Harrison Brady (a fictitious stand-in for William Jennings Bryan) as “the champion of ordinary people, like us,” the cynical newspaperman E. K. Hornbeck (modeled after H. L. Mencken) differs.

“Wake up, Sleeping Beauty,” Hornbeck tells her. “The ordinary people played a dirty trick on Colonel Brady: They ceased to exist. Time was when Brady was the hero of the hinterland, water-boy for the great unwashed. But they've got inside plumbing in their heads these days! There's a highway through the backwoods now, and the trees of the forest have reluctantly made room for their leafless cousins, the telephone poles. Henry's Lizzie rattles into town and leaves behind the Yesterday-Messiah standing in the road alone, in a cloud of flivver dust. The boob has been de-boobed. Colonel Brady's virginal small-towner has been had — by Marconi and Montgomery Ward.”

Philadelphia’s smartest man

Today, thanks to TV, interstate highways, and the Internet, you can be just as connected to the world in Egypt, Texas or Hawthorne, Nebraska as you are in New York or Paris. Conversely, the celebrated neighborly virtues that were traditionally associated with small towns are now most likely to be found only in pedestrian-friendly urban downtowns — places like Center City Philadelphia or Manhattan’s Upper West Side or Park Slope in Brooklyn, where people interact with each other and with shopkeepers on foot rather than behind the wheels of their cars or in faceless chain stores in shopping malls.

I write as a confirmed urbanite who has lived in three of the world’s great cities — New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia — as well as one very small county seat town: Portland, Indiana (population 7,000). Like Carol Kennicott in Main Street, I too experienced a culture shock upon my arrival in Portland in 1964. But my foil on my very first day there was not a naïve country girl like Bea Sorenson but a savvy Portland native who (like me) had just graduated from college and was about to leave his hometown permanently to pursue his career hundreds of miles away.

“You will be amazed at the number of really intelligent people you meet here,” he told me. “You will also be amazed by the number of really stupid people you meet here.”

In retrospect, he was right on the money — and of course his assessment could be applied to New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia as well. Or have you forgotten that former State Senator Vincent Fumo — aka “Philadelphia’s smartest man” — somehow maneuvered himself into a 55-month prison term?

Twyla Tharp, too

The “really intelligent” people who came out of Portland, Indiana, included Elwood Haynes, who invented the clutch-driven automobile in 1894, and the Morgan Stanley investment banker Mary Meeker, aka “The Queen of the Internet,” whose skillful promotion of Silicon Valley start-up companies in the 1990s made the Internet commercially feasible for the first time. I invite you to imagine what your life would be like without automobiles or the Internet.

For good measure, Portland also produced the innovative choreographer Twyla Tharp and the movie actor Leon Ames, who cofounded the Screen Actors Guild in 1933. But of course every town in America could trot out a similar honor roll. Small towns often produce overachievers — not to mention U.S. presidents like Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton — because, having grown up where they can make a difference in their community, it never occurs to them that they can’t make a difference in the world, too. Is it time, maybe, for artists and writers to trash the old Sinclair Lewis stereotype for something more nuanced?

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg