Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The illusionist

Jimmy Tayoun, performance artist

When the former journalist, restaurateur, politician, publisher, and convicted felon James Tayoun died last week at the age of 87, the Philadelphia Inquirer headline called him “a colorful Philadelphia character.” As a general rule of thumb, whenever you see someone described in the media as a “colorful character,” you should drop whatever you are doing and run away.

But the city where young Jimmy Tayoun found himself in the mid-20th century was, in fact, desperate for a touch of color. It was a city notorious for Sunday blue laws, squat buildings, fleabag hotels, bad food, undrinkable water, sleazy night life, and tepid newspapers.

In this “Workshop of the World,” as Philadelphia then styled itself, hundreds of thousands of human drones spent their waking hours performing bloodless tasks from one decade to the next at huge, faceless, and seemingly permanent institutions such as the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Penn Mutual Life Insurance Company, Scott Paper, Sun Oil, Horn & Hardart, and the First Pennsylvania Bank— jobs they nevertheless cherished because, after all, they had lived through the Great Depression, when many people had no jobs at all.

This was the dreary city ridiculed in a thousand jokes by comedians, from W.C. Fields (“Last week I went to Philadelphia, but it was closed”) to Fred Allen (“My Philadelphia hotel room was so small that the moths had to walk across the floor for lack of space to spread their wings”). In such a place, a glib, charming, energetic, audacious hustler like Tayoun would be forgiven almost anything — especially the lack of substance beneath his shiny façade. It was impossible to dislike him, even if you disliked what he stood for.

Belly dancers

The thread connecting Tayoun’s various careers was his instinctive talent as a performer. Although Tayoun never (to my knowledge) worked professionally as an actor, he intuitively grasped Shakespeare’s advice that the world’s a stage and the play’s the thing. He understood the importance of one’s costume: Shortly after his release from 40 months in prison (for paying and accepting bribes), Tayoun showed up at the Mummers' Parade in a cashmere coat, a tailored suit, and spit-shined shoes, looking more mayor than ex-con. He knew how to size up an audience and pander to it: his tenures in both the state legislature and city council were distinguished primarily by his remarkable talent for coming on like Frank Rizzo in South Philadelphia and like Adlai Stevenson in Center City. He knew how to ingratiate himself with impressionable journalists hungry for lively copy.

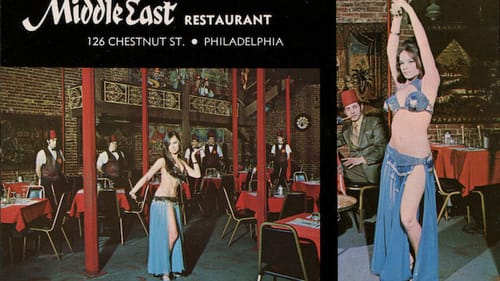

As the son of Lebanese Christian immigrants, Tayoun lacked the basic building block of a Philadelphia political career: an ethnic constituency. Consequently, he had to work harder at it. He first built a following by opening (with his brother) the restaurant Middle East in South Philadelphia. In a city whose idea of dining out in 1958 was snapper soup at Bookbinder’s, the Tayoun brothers’ then-exotic delicacies — shish kebab, hummus, baba ganoush — came as a revelation, as did the belly dancers they added when the restaurant moved to Old City in 1969. By demonstrating that a restaurant could be fun and even adventurous, Middle East played a significant role in lifting Philadelphia nightlife out of the dark ages.

But Tayoun hungered for a larger stage. By 1969 he had parlayed his various followings into a seat in the state legislature, followed by a long stint in the Philadelphia City Council.

‘Let ’em clap’

Tayoun in action was akin to Laurence Olivier throwing himself into a role like Hamlet — except that, for Tayoun, the curtain never came down. In 1984, when he audaciously challenged incumbent Philadelphia congressman Tom Foglietta, the two candidates squared off in a raucous debate at which Tayoun’s South Philly supporters, egged on by their candidate, applauded, whistled, and cheered for Tayoun to such a ludicrous extent that they repeatedly drowned out their own candidate. But there was a method to this apparent madness: the cheers occurred whenever Tayoun raised his voice, thus creating the impression that Tayoun had scored some telling point while simultaneously preventing the rest of the audience from hearing for themselves whether Tayoun was spouting sense or nonsense.

During one exchange that night, when the moderator asked Tayoun’s supporters to stop applauding so their own candidate could be heard, Tayoun countered, “Let ‘em clap. I don’t mind.”

Office hours

Tayoun’s political popularity ostensibly derived from his zealous attention to his constituents’ petty needs, from pothole repairs to street cleaning to cutting through bureaucratic red tape. But I once stumbled into a political gathering where aides to then-mayor Frank Rizzo were amusing themselves by exchanging “Tayoun stories.” As they told it, once a week Tayoun held evening office hours where constituents sought his help. Whatever the request, Tayoun would respond empathetically and promise to fix the problem and the constituent would depart happy, whether the problem ever got fixed or not. In some cases, Tayoun would angrily pick up the phone, call the “mayor,” and demand action on the constituent’s behalf; as it turned out, the fellow on the other end of the line was one of Tayoun’s own flunkies. If this story was true, it suggests Tayoun understood a basic human truth: in an impersonal world, most people can be won over if you simply give them a receptive ear.

Were these stories true? I don’t know. But they do suggest how Tayoun was regarded by his fellow politicians.

Victim or victimizer?

Whenever Tayoun ran for office, his campaign posters plastered every utility pole and vacant wall throughout his district, creating the impression that armies of enthusiastic Tayoun supporters were hard at work. But early one Sunday morning during one such campaign, a friend of mine in Society Hill noticed a lone campaign worker industriously attaching Tayoun posters to every available surface. Who was that campaign worker? You guessed it: Jimmy Tayoun.

The notion that his habitual embrace of bribery might have been a corrupting influence on society was something he steadfastly refused to consider; as he once described that chapter of his life, “I went into politics, and I wound up in prison.” In his own mind, he was the victim, never the victimizer.

After his release from prison, Tayoun wrangled a gig as host of a Sunday-morning radio talk show and invited me on as a guest. I naively perceived an opportunity to engage in dialogue about life lessons learned, but Tayoun skillfully steered the conversation in an entirely different direction. To hear him tell it, my presence on his show was itself proof of his rehabilitation. As the Inquirer columnist Clark DeLeon once observed, Tayoun was a man blissfully devoid of a sense of shame.

Journalists confronting daily deadlines — not to mention the rest of us — constantly go belly-up for “colorful characters.” Philadelphia is a much more exciting place today than it was when Tayoun came on the scene. If we see his like again, and we will, I'd like to believe we might look beneath the style for evidence of substance. You know — the way we did with Donald Trump.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg