Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Who tells your story?

Central City Opera's 'The Ballad of Baby Doe,' and Leadville's 'Fiddler'

The place where I spend my summers, the small mountain town of Leadville, Colorado (pop. 2,580) recently announced auditions for a community production of Fiddler on the Roof. The show would also be staged in a church. To be sure, it’s a really nice church, but at first, the whole endeavor struck me as odd.

Leadville has a rich Jewish history. Both the Guggenheim and May families got their start here, one pulling silver out of the soil, the other selling clothing and supplies to miners. At the height of the 1800s silver boom, there were four synagogues in town — a town that vied with Denver for the title of state capital (Leadville was too remote, so Denver won).

Sunrise, sunset

Today, there’s still a one-room synagogue, but that’s a museum, open mostly due to one part-time resident’s tireless efforts. The old Hebrew cemetery, which sits inside the larger Evergreen cemetery, but like the Catholics, Odd Fellows, and others, is separated by a fence, gets a cleanup every year. The congregation that performs this mitzvah carpools an hour in over Tennessee Pass from Vail because there are almost no Jews left in town to do the job.

As far as theater goes, Leadville doesn’t have many (okay, any) options. Denver prides itself on its status as the Mile High City; Leadville is a mile higher. But while Denver and Boulder — not to mention Leadville’s nearby mining-legacy cousins, Vail and Aspen — enjoy vibrant year-round arts and culture programming, Leadville has exactly one crumbling performance venue, the Tabor Opera House, and even that nearly brought down its final curtain this summer, 137 years after "Silver King" Horace A. W. Tabor opened its doors.

The reasons Leadville still struggles while so many other mountain towns struck it rich, have something to do with the switch from the silver standard to gold, and a little to do with hard-rock-miner culture, which is as rugged and stubborn as it sounds. Alongside neighborhoods of dollhouse Victorians, there are trailer parks, dilapidated log cabins, and a proliferation of empty storefronts on Harrison Avenue, the town’s main drag.

Things are also changing. There is a large community of Mexican immigrants. Front Range refugees are buying up weekend homes, and the rental market is packed with young people. Ultra athletes flock here for the famed Leadville 100-mile mountain bike and foot races. (Former Philly Mag writer Christopher MacDougall’s book, Born to Run, chronicles the barefoot runners of Mexico’s Tarahumara tribe and their competitive successes here.)

Gold is a fine thing

Throughout, the Tabor has provided entertainment. Harry Houdini and Buffalo Bill performed there. Oscar Wilde, after a day spent drinking and socializing in the mines, emerged to give a lecture on interior decorating. In recent years, performers from all over the country have made their way up Fremont Pass to the Tabor’s stage.

But one production, as far as I can tell, never appeared there. In 1956 — this year marks its 60th anniversary — Douglas Moore and John LaTouche premiered a landmark U.S. opera, The Ballad of Baby Doe, at the Central City Opera. The venue is just a few miles down the mountain from Leadville, where the story’s legendary riches-to-rags love triangle occurred, and the opera house where much of its first act takes place. (Unsinkable Molly Brown also lived here, but that’s another story for another time.)

That Central City won the rights to Tabor’s own tale is typical of both his and Leadville’s history of misfortune. Some locals are still downright resentful that another town gets to tell their story.

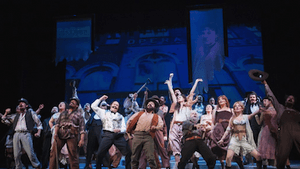

Central City resurrects the production once a decade, and this summer, it featured Wilmington, Delaware’s own baritone Grant Youngblood as Horace Tabor, Leadville mayor, millionaire, and cautionary tale. It was a beautiful, understated production, and between Ken Cazan’s naturalistic direction, Sara Jean Tosetti’s grit-and-grime-dusted costumes, and David Martin Jacques’s projections, featuring 1800s Leadville, and yes, the Tabor’s once-grand façade, it was unexpectedly touching.

To me, the show felt both noble in its simplicity and heartbreaking. I would soon drive home past Baby Doe’s once-luxurious top-floor lookout in the former Tabor Grand Hotel, where she could see all the way to her husband Horace’s Matchless Mine, never knowing she’d someday freeze to death a pauper on its grubby cabin floor. I watched projections of the Tabor Opera House and Leadville’s long-gone society, and I, too, while entranced, felt a pang of regret that Leadville didn’t get to stake its own claim on this work, one that might have saved the Tabor.

Grubstaking the arts

As it happens, shortly after The Ballad of Baby Doe closed, Leadville received a $300,000 Colorado Department of Local Affairs grant. The city could purchase the opera house, save it from certain ruin, bring in visitors, and provide entertainment for locals.

This sort of development, the opportunity to create a live arts community from the ground up, doesn’t happen often. In Philadelphia, we have so many options that we stay home just to take a break. Up here, the impact of one working venue solely devoted to performance might be life-changing.

So, Central City has a lot of casinos and also Baby Doe’s opera. They’ve done a great job of maintaining the quality and strength of its legacy. One hopes, with the purchase and restoration of the Tabor Opera House, Leadville will claim another story — perhaps capitalizing on that Wilde visit, or creating something entirely new that will emerge just by virtue of having a space, government support, and interest coalescing at the same time.

This brings me back to Fiddler. Its director is the Leadville high school’s new director of choral and theater activities. By all accounts, he’s passionate about the arts in general, and about bringing them back to the Tabor in particular. I have to trust that his choosing this musical wasn’t an accident, that while it’s true there may not be any Jewish people involved with the production, he will tell the story with respect, and connect it to the town’s history. People around here are excited about it and that can only be good, right?

Maybe, if Central City hadn’t won the rights to that opera, Baby Doe’s story might have fallen into disuse, along with the Tabor. Maybe, if Fiddler wasn’t produced here, Leadville’s citizens might not learn about their home’s Jewish heritage, or what some of those cemetery residents endured before they arrived, or even, at its most basic, the transporting power of theater. It’s a complicated question, who gets to tell someone else’s story, but if the end result serves the greater good, well then, I’m willing to say l’chaim.

What, When, Where

The Ballad of Baby Doe. Opera by Douglas Moore. Libretto by John Latouche. Ken Cazan directed; Timothy Myers conducted. Through Aug. 4, 2016 at the Central City Opera, 124 Eureka St., Central City, Colo. (303) 292-6700 or centralcityopera.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Wendy Rosenfield

Wendy Rosenfield