Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Be careful what you wish for

Arts criticism: Decline and fall

In her inaugural column last week, BSR’s new editor Wendy Rosenfield sheepishly recalled “a time not so long ago when I declared openly, and probably somewhere in the comments section of one of his more controversial pieces, that I disagreed with Dan Rottenberg's opinions so strongly I would never, ever write for BSR in general or Dan in particular.”

I’m not sure whether Wendy intended that comment as a reflection on me or on her. Maybe on both of us?

More to the point, people and institutions inevitably change with the passage of time. On at least one issue of disagreement between us — the role of critics in society — it’s not only Wendy and I who have evolved but also the issue itself.

Royster’s advice

As an editor, I’ve devoted much of my career to promoting alternatives to mainstream journalism. In junior high and high school, I cranked out (on a rexograph machine) my own weekly class newspaper, which took potshots at the school’s policies, teachers and even the principal. In Chicago in 1968, I was one of the defiant journalists who banded together after the Democratic convention riots to launch the monthly Chicago Journalism Review, in which we critiqued our own newspapers and reported the stories they suppressed for fear of offending the city’s mayor-for-life, Richard J. Daley.

As a critic, my anti-establishment instincts were inadvertently reinforced by my boss at the Wall Street Journal, the legendary Vermont Royster, when he told me: “You get can opinions from any cab driver. What matters is the insight you bring to the reader.” They were further bolstered at a party in 1971 when, shortly after I became the film critic for Chicago magazine, I was besieged with requests for my verdicts on various flicks until one astute friend remarked, “You know, two months ago nobody gave a shit what you thought about movies.” He was right: As Vermont Royster had noted, ultimately what mattered was not my title but whether I brought something of value to the conversation.

At the Welcomat (now Philadelphia Weekly) from 1981 to 1993, I dedicated that paper to the revolutionary notion that (as I wrote at the time) “there is more than one way to get at the truth, that society must constantly evolve new ways to get at the truth, and that such evolution can come about only through vigorous experimentation — a process which, by definition, involves taking risks and even making mistakes.” The greatest impediment to such progress, I argued, was “the sort of well-meaning people” who belong to journalism societies — “people anxious to promote the concept of professional standards so as to enhance the credibility of all journalists.” That was a noble cause, I acknowledged, “but too often its pursuit involves stamping out anything that smacks of deviation from conventional practice.”

Sinking ship

Thus, when I launched BSR in 2005, I audaciously sought to dismantle the artificial wall separating professional critics from amateurs. At BSR, I declared, we would reject the pompous notion — promoted for a century by the likes of the New York Times, the New Yorker, and the Inquirer — of the critic as a high priest dictating which art works shall survive and which shall perish. At BSR, by contrast, anyone with insight — professionals, amateurs, audience members, whatever — could play critic. And instead of posting a single review of each play or concert or art exhibit, we often posted multiple reviews — sometimes even three or four (and still do).

At the very moment we at BSR were promoting this radical approach to criticism, Wendy was working her way up to become a theatrical high priestess at the ultimate Philadelphia establishment medium — the Inquirer. As an executive committee member of the American Theater Critics Association, she also became an outspoken advocate of professional standards of criticism — only to discover, once she reached that lofty plateau, that the Inquirer was a sinking ship casting its full-time arts critics and its exalted standards overboard in a desperate effort to stay afloat.

Today metropolitan newspapers that once boasted full-time senior and junior theater critics employ no full-time theater critics at all; the Inquirer retains just four full-time arts writers on its payroll and pays its free-lance critics barely more than BSR does; the Internet is inundated with instant opinion polls and bloggers who happily broadcast their often uninformed views for no compensation whatever; and a critic like A.O. Scott of the New York Times feels required to write an entire book (Better Living Through Criticism) arguing that informed criticism “is one of the noblest, most creative, and urgent activities of modern existence.”

Searching for authority

I still believe in speaking truth to power. But where’s the satisfaction in speaking truth to once-powerful critics who can now be found hawking apples and opinions on street corners for $5 a throw?

"Try to imagine a world in which the only outlets for communication are the huge institutional media that can afford expensive lawyers," I wrote in The Quill, the Society of Professional Journalists' monthly magazine, in 1985, when the Welcomat was fighting two libel suits. "That could be what our world is coming to. It would be a very 'professional' world, to be sure. But does anyone really believe that the world will be a better place when no one but professionals can be heard?" How was I to know that I would one day inhabit a world where everyone except professionals could be heard?

So you might say I got what I wished for, to my regret. When I first jumped into the criticism game, someone needed to knock the high priests of arts criticism off their snooty pedestals. But in the age of the Internet and cable TV, we need the opposite: clearly defined voices of authority, as well as outlets that will support them full-time and maybe even provide them with health insurance and retirement benefits.

So there you have it: Wendy and I agree on something. At least for the moment. And if we disagree, so what? I could be wrong, so it’s always useful to listen to people who differ with me.

From what I’ve seen and read of Wendy, she believes in expressing strong ideas and encouraging others to do the same. Me too. Now, there’s something we agree on that really matters.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

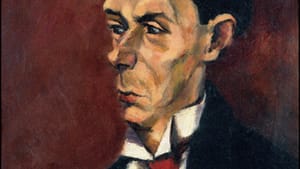

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg