Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Correcting our whitewashed history

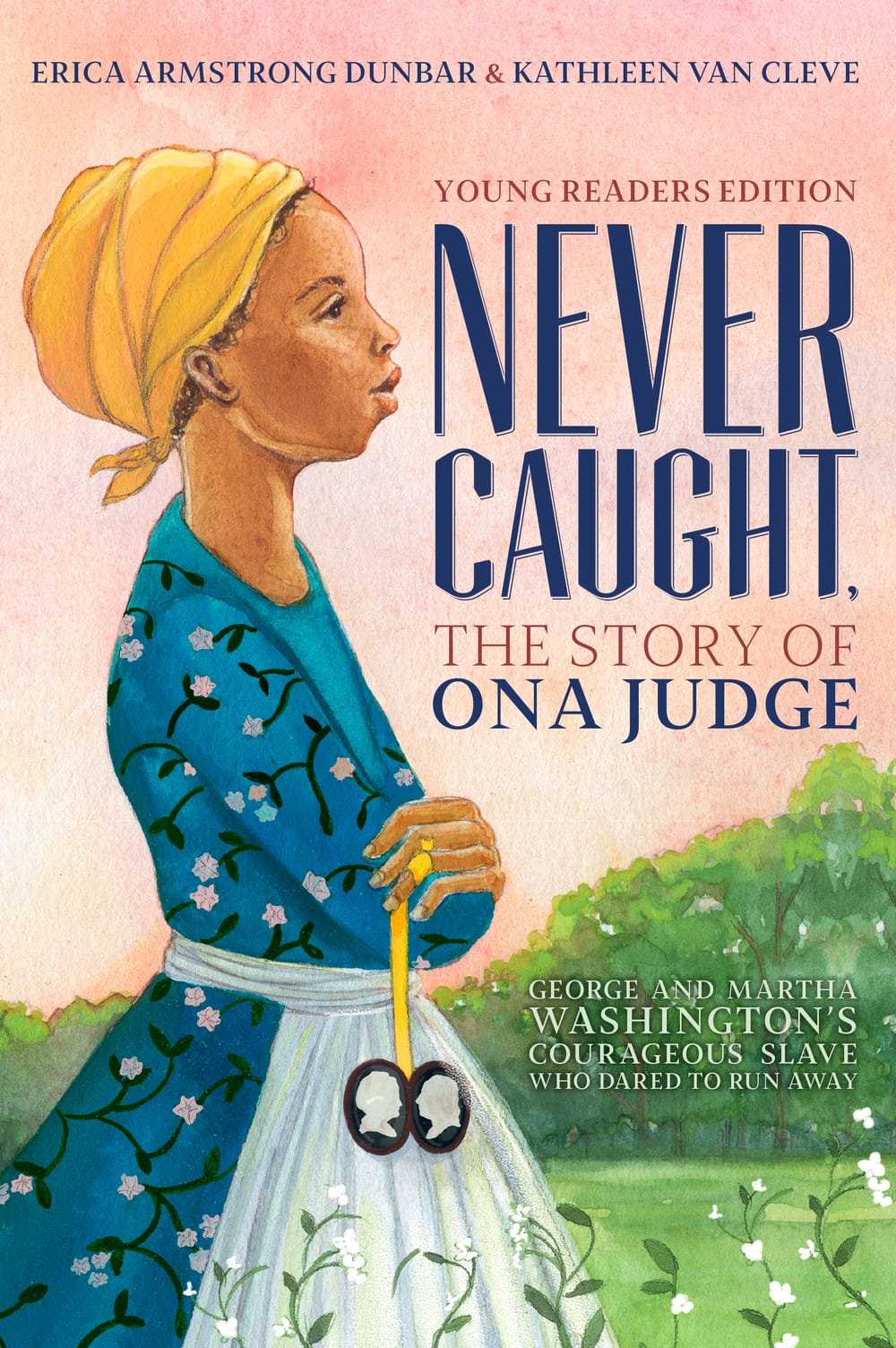

The Young Readers Edition of ‘Never Caught,’ by Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Kathleen Van Cleve

The summer I was 12, I spent weekday mornings on the tennis courts at Friends Central School in Wynnewood, swinging a clumsy backhand and counting the minutes until lunch. Each afternoon, I parked myself under a maple tree and devoured Gone with the Wind while sipping a Diet Coke.

We could argue about which was the greater poison.

I’d say the book. Because, while I never finished an entire can of soda, I gulped every morsel of Margaret Mitchell’s romanticized South, including the images of loyal, hardworking, genial slaves whose ministrations made Scarlett long for the antebellum days when all was ducky.

The way things were

I wish someone had pointed out that I was lolling on a campus founded by Philadelphia Quakers, many of whom who drew the line against slavery almost 200 years before the Civil War. And then, I wish someone had thrust a book like Never Caught: The Story of Ona Judge, George and Martha Washington’s Courageous Slave Who Dared to Run Away into my hands.

This book, the young readers’ version of Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s Never Caught — a 2017 National Book Award finalist in nonfiction — is a welcome, compelling corrective to the whitewashed version of Revolutionary-era history I received: a story in which the Anglo men were heroes, the black people were nameless, and slavery was simply, unquestionably, The Way Things Were.

Condemning slavery

Dunbar, a Rutgers University historian who coauthored the young readers’ version with University of Pennsylvania professor Kathleen Van Cleve, wanted to help fill an aching gap in the historical narrative.

As a student at Germantown Friends School in the 1980s, Dunbar says, “I learned very little about American slavery. It bothered me. I kept asking: Why am I not encountering people who look like me in our narratives?”

The book isn’t a diluted version of the adult Never Caught. In some ways, it delivers more than the original: a map of the Eastern Seaboard, a timeline from 1731 (Martha Washington’s birth) to 1848 (Ona Judge’s death), and the transcript of an interview Judge gave to a New Hampshire newspaper in 1845.

The young readers’ text is more emphatic about condemning slavery (described as “a grotesquerie,” an “abomination,” and a “disease”). It underscores the role of individuals, including George Washington, in furthering that system for their own wealth and comfort. It highlights the people and groups who were ahead of the abolitionist curve (like those Philly Quakers, along with Benjamin Franklin and Washington’s own secretary, Tobias Lear).

Centering Ona Judge

Most significantly, this version foregrounds Judge, who, as a 22-year-old woman owned by the most powerful couple in America, walked out of the president’s house one May evening and never came back.

The centering of Judge’s story is evident on the cover. While the adult book features portraits of George and Martha Washington, the young readers’ version has an artist’s rendering of a black woman, her gaze straight ahead, her arms resolutely crossed. Dangling from one finger — an ambivalent keepsake? a reminder that while she escaped, she was never legally freed? — is a locket with cameo images of the first president and his wife.

The text emphasizes the pluck, strategizing, and support (from Philadelphia’s free blacks, including Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church) that it must have taken for Judge to flee, sail to New Hampshire, and establish a life that included work, marriage, and motherhood, all while eluding the president’s tireless efforts (sometimes in violation of his country’s just-minted laws) to pursue and bring her back to his home.

Opting for the truth

Dunbar and Van Cleve deliberately seed their book with teachable moments about conscience, power, and resistance. (They are collaborating on a curriculum to accompany the text.)

“Washington, by the latter moments of his life, began to really question slavery, at the same time he’s relentlessly pursuing Ona,” Dunbar says. “We wanted young readers to see that people can say one thing and do another. And to understand that someone as mythic and iconic as Washington had human flaws, just like everyone else.”

Dunbar and Van Cleve wrestled over how to introduce disturbing facets of history, such as the rape of enslaved women by their enslavers or other white men.

In that and other instances, they opt for simply stated truth. A section about Judge’s parents — Andrew Judge, a white indentured servant, and an enslaved woman named Betty — reads, “They may have had the kind of relationship that is the opposite of love, the kind of nonconsensual encounter where a man uses his strength and privilege to overpower the woman…. His status as a white man would have protected him, just as it did the white male owners who commonly raped the women they owned.”

Especially since #MeToo has brought endemic sexual harassment and abuse into public consciousness, I believe that’s not too much information for a 10-year-old.

Only one way?

Teaching young people about slavery is fraught territory; recall the 2016 picture book A Birthday Cake for George Washington, so roundly condemned for its portrayal of the enslaved chef Hercules cheerfully concocting pastry for the president that Scholastic yanked it from distribution.

Never Caught was vetted before publication — not only by its authors but by staff members of the social-justice nonprofit Teaching for Change, who spotted at least one reference they thought justified slavery: “Like all plantation owners in the South, George also knew there was only one way to be successful. Slaves.” I didn’t read it that way — I thought it referred truthfully to the plantation economy and the mindset of the time — but Dunbar had already ordered a correction. The final version says instead, “George knew that if he exploited the labor of slaves, he would make more money.”

Dunbar and Van Cleve, who led a workshop for young writers and read from the book in January at the Museum of the American Revolution, hope Judge’s story will inspire young people to become writers and historians. I hope so, too. Particularly at this fraught moment, we need more stories to bust the myths of American history and expose the truths of our nation — the ideals, the stains, and the enduring contradictions.

What, When, Where

Never Caught: The Story of Ona Judge, George and Martha Washington’s Courageous Slave Who Dared to Run Away. By Erica Armstrong Dunbar and Kathleen Van Cleve. New York: Aladdin, 2019. 252 pages, hardcover; $18.99. Available from Simon & Schuster.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman