Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

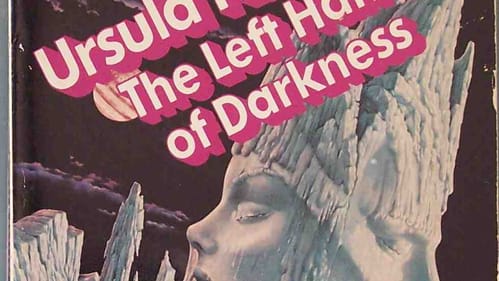

Mistress of the multiverse

Remembering author and inspiration Ursula K. Le Guin

The first time I met Ursula K. Le Guin, she was holding a plate of scrambled eggs.

It was 1989, and Le Guin was an instructor at Flight of the Mind, a workshop for women writers held at a rustic Dominican Catholic retreat center in McKenzie Bridge, Oregon. I was there for a class in creative nonfiction.

Not long before the workshop, I read a story of Le Guin’s in the Oregonian Sunday magazine. It was a brief shimmer of a tale about a woman who is unsure of her purpose and sees messages everywhere: in the whorled pattern of a dress, in the scudded script the ocean leaves on shore.

Back then, I was a new and nervous writer, edging across the bridge from journalism to short story and memoir. Terse rejection notes stuffed a manila file in my desk.

I shuffled up to Le Guin — the corduroy-clad luminary with 22 books to her name — and told her how much I loved her story. “Thank you,” she said. “You know, my agent sent that piece out 16 times.”

Feminist fantasy

The night before, Le Guin was tasked with a ritual she repeated each year she taught at Flight: welcoming participants with a poem celebrating the group’s diversity and reassuring anyone who felt out of place. She knew what phrase came next — she wrote the thing, after all — and couldn’t help chuckling preemptively as she slouched at the microphone, her voice all Oregon, like moss on slate.

“Some of us are Jewish, and some of us are goyish… Some of us are girlish, and some of us are boyish.” Later in the piece, she rhymed “vegetarian” with “Presbyterian.” Everyone laughed, which was the point, and relaxed, which was really the point, and Le Guin returned to her seat with a wink.

After Le Guin’s death on January 22, 2018, Elliott bat Tzedek — events coordinator at Mt. Airy’s Big Blue Marble Bookstore — came to work and told her colleagues they should build a display of favorite Le Guin titles. They shook their heads. Customers, some in tears, had already cleaned out the shelves.

“She meant so much to so many different writers,” bat Tzedek says. “People just wanted to come in and be someplace where people knew who she was. And they knew we would have her books.”

The store will honor Le Guin on February 24, 2018; local writers, including novelist Simone Zelitch and mystery/thriller writer Jon McGoran, will discuss Le Guin’s influence on their work and share some favorite excerpts. I’ll be among that lineup, too.

It will be hard to choose the most resonant words. As soon as I learned of her death, I reached for Sixty Odd, Le Guin’s 1999 collection of poems, tucked in my dining room next to her translation of the Tao Te Ching. On other shelves, in other rooms, we have Dancing at the Edge of the World, a collection of essays, and a much-thumbed copy of The Left Hand of Darkness. The latter is a groundbreaking novel in which Le Guin posited a genderfluid world back when “T” was barely a caboose on the LGBT acronym.

Bat Tzedek recalls, “The first Le Guin I remember reading was The Left Hand of Darkness. I was in Madison, coming out and hanging out with all the lesbian feminists. That’s the one I first really remember shaking me up: 'Oh, you can have a world like this.'”

Getting to "yes"

Le Guin was fierce and wry, unpretentious and uncompromising. She was opinionated and, at the same time, willing to publicly change her mind; Dancing at the Edge of the World includes an essay rethinking her own earlier writing about feminism and gender.

She aged honestly: nickel-hued hair, her expressive face mapping bemusement, insight, or outrage, depending on the moment. Le Guin refused to be pigeonholed. Yes, she wrote science fiction/fantasy, but also essays, short stories, poetry, children’s literature, searing letters to the editor, a writer’s guide, blog posts, and uncategorizable offerings, such as the chapbook A Winter Solstice Ritual from the Pacific Northwest, penned with science-fiction writer Vonda N. McIntyre.

Her words found me exactly when I needed them. At a time of existential uncertainty, I discovered “A Left-Handed Commencement Address,” given at Mills College in 1983. Le Guin told graduates, “You will find yourself — as I know you already have — in dark places, alone, and afraid.” She insisted that such abysses also cache hope, “not in the light that blinds, but in the dark that nourishes, where human beings grow human souls.”

Le Guin championed art, language and imagination. She decried capitalist greed, commodity publishing, and gender-coded niceties. She wrote prolifically, extravagantly, ecumenically, right until the end.

A few days after her death, my family read one of her poems at the Shabbat table. A few days after that, my partner, our daughter, our housemates, and I watched Le Guin’s smackdown speech at the 2014 National Book Awards.

It was a rough week in my writing life: one essay rejected by three different editors, another returned with a crosshatch of comments and questions. I pulled down Le Guin’s Steering the Craft: A 21st Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story. “To learn to make something well can take your whole life,” she wrote. “It’s worth it.”

I thought about the story I had savored 29 years earlier, the one that bounced off more than a dozen editors’ desks before someone finally said yes.

Then I opened my laptop and went back to work.

What, When, Where

Remembering Ursula K. LeGuin: Philadelphia Writers on LeGuin’s Influence. February 24, 2018, at the Big Blue Marble Bookstore, 551 Carpenter Lane, Philadelphia. (215) 844-1870 or bigbluemarblebooks.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman

Illustration by Hannah Kaplan

Illustration by Hannah Kaplan